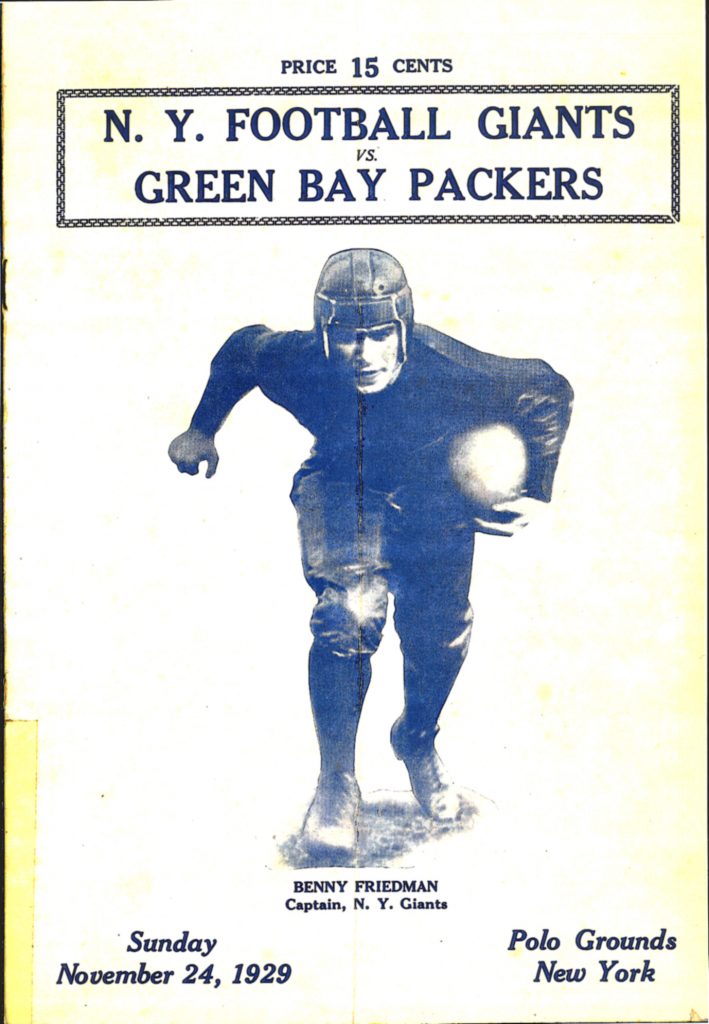

New York Giants vs Green Bay Packers Game Program – Courtesy of Rev. Mike Moran

[contentblock id=1 img=html.png]

The recent election of Harry Carson into the Pro Football Hall of Fame spurred me to write this article. Carson, one of the greatest middle linebackers ever to play the game, was first eligible for the Hall of Fame in 1993. He had to wait 13 long years before receiving confirmation of his acceptance. But at least Carson is alive to enjoy his personal triumph. Unfortunately, for another Giant great, Benjamin “Benny” Friedman, the honor came far too late.

Most football fans today, including Giants fans, have never heard of Benny Friedman. That’s too bad because not only was Friedman one of the greatest quarterbacks ever to play in the NFL, he, in fact, revolutionized the pro game by becoming the League’s first great passer. There are only four quarterbacks with ties to the Giants in the Hall of Fame: Y.A. Tittle, Fran Tarkenton, Arnie Herber, and Benny Friedman. The two longest tenured quarterbacks with the team – Phil Simms and Charlie Conerly – are not in the Hall. Yet Friedman’s induction in 2005 went barely noticed by the media and fans. Even the Giants organization did not publicize it much.

So who was Benny Friedman? Friedman, arguably the greatest Jewish athlete of all time, certainly did not look the part. He was approximately 5’8” and only 170 pounds. But the Giants were so enamored with his skills that they completely dismantled another NFL team in order to acquire him. During the NFL’s early days, no one could throw the football like Friedman.

Friedman was a two-time All-American quarterback at the University of Michigan and nationwide collegiate star of the first order. In 1925 and 1926, he led Michigan to back-to-back 7-1 seasons and first place finishes in the Big Ten. Against the University of Indiana in 1925 (the same year the Giants came into existence), Friedman accounted for 44 points, throwing for five touchdowns and kicking two field goals and eight extra points. At the time, only the legendary “Galloping Ghost,” Hall of Fame halfback Red Grange, received more attention with his decision to turn pro (Grange was as famous an athlete in those days as Babe Ruth). With no NFL Draft in existence, Friedman signed with and started his NFL playing career with the Cleveland Bulldogs in 1927. A year later, the franchise moved to Detroit and became the Wolverines. Following the 1928 season, then Giants’ owner Tim Mara made a strong push to obtain Friedman, who had burned his team a couple of times. But the Wolverines would not trade him. Mara made four ever-stronger offers, yet was rebuffed each time. Mara’s solution was to buy the financially-troubled Wolverines and disband them two days later. He kept Friedman, the head coach (as part of the deal), and a few other players. To make Friedman happy, Mara paid him an annual salary of $10,000 – the most ever for a football player at a time when most players were earning $50-100 a game.

Mara made the move to obtain Friedman both for player personnel and economic reasons. The Giants won their first NFL title in 1927 with an 11-1-1 record (the team’s only loss being to Friedman’s Bulldogs). However, in 1928, the Giants fell to 4-7-2. And worse, with the Great Depression looming on the horizon, the Giants were losing money and in dire financial straits. It was hoped that Friedman would not only turn around the win-loss record, but his star-power would also put the team in the black – and that’s exactly what he did, perhaps saving the franchise. It also didn’t hurt that Friedman was Jewish and would be playing in a city heavily populated with Jews. The Giants reportedly lost $54,000 in 1928. But upon Friedman’s arrival at the Polo Grounds, fans began showing up at Giants games and the team turned a profit in his first year in New York. The Giants made $8,500 in 1929, $23,000 in 1930, and $35,000 in 1931 in Friedman’s three Depression-era seasons with the team.

Friedman only played three years for the Giants. But those three years in New York solidified his status as the NFL’s first great passer. Back in those days, the game’s rules were not conducive at all to passing. Roughing the passer was legal. If a quarterback threw two consecutive incomplete passes, the team was penalized. An incomplete pass in the opposition’s end zone resulted in a turnover. Most importantly, the ball was much rounder and harder to grip. That did not matter to Friedman, who had incredibly strong hands. “I think the most amazing thing about him was the way he could throw the kind of football that was in use in his days,” said Giants’ co-owner Wellington Mara, who passed away in 2005 at the age of 89. “Did you ever see that ball? It was like trying to throw a wet sock.”

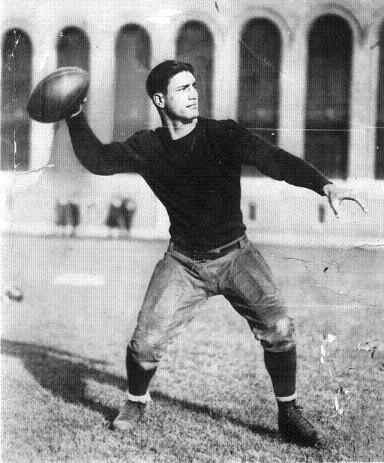

Benny Friedman with the Detroit Wolverines

In each of his first four years in the NFL, including his first two with the Giants, Friedman won first-team All-NFL honors and led the league in passing touchdowns. Although complete statistics were not kept, it is believed that Friedman completed more than half of his passes at a time when a 35 percent completion percentage was considered a very good performance. He led the league in touchdown passes each of his first four years. He twice passed for more than 1,500 yards in a season – an unheard of total for that era. In fact, no other NFL passer would reach that mark until 1942. From 1927 to 1930, Friedman threw for 50 percent more yards and twice as many touchdowns than the next-best quarterback in the NFL.

In his first year with the Giants in 1929, Friedman threw 20 touchdown passes, including four in one game – the first player to do either in the League. No NFL team would surpass 20 passing touchdowns in a season until 1942 and that total would have still led the NFL as late as 1977. The Giants’ 312-point total that year marked only the second time the 300-point barrier had been broken in the League. But it would happen again in 1930 when Friedman quarterbacked the team to 308 more points.

In the multi-tasking, two-way days of the early NFL, Friedman could do more than pass the football. Friedman could run, kick, and play defense. In 1928, the year before he came to the Giants, he led the NFL in both rushing and passing touchdowns – something no other player in NFL history has accomplished. He also led the league in extra points that season. In one game against the Bears, he rushed for 164 yards. Friedman also played defensive back.

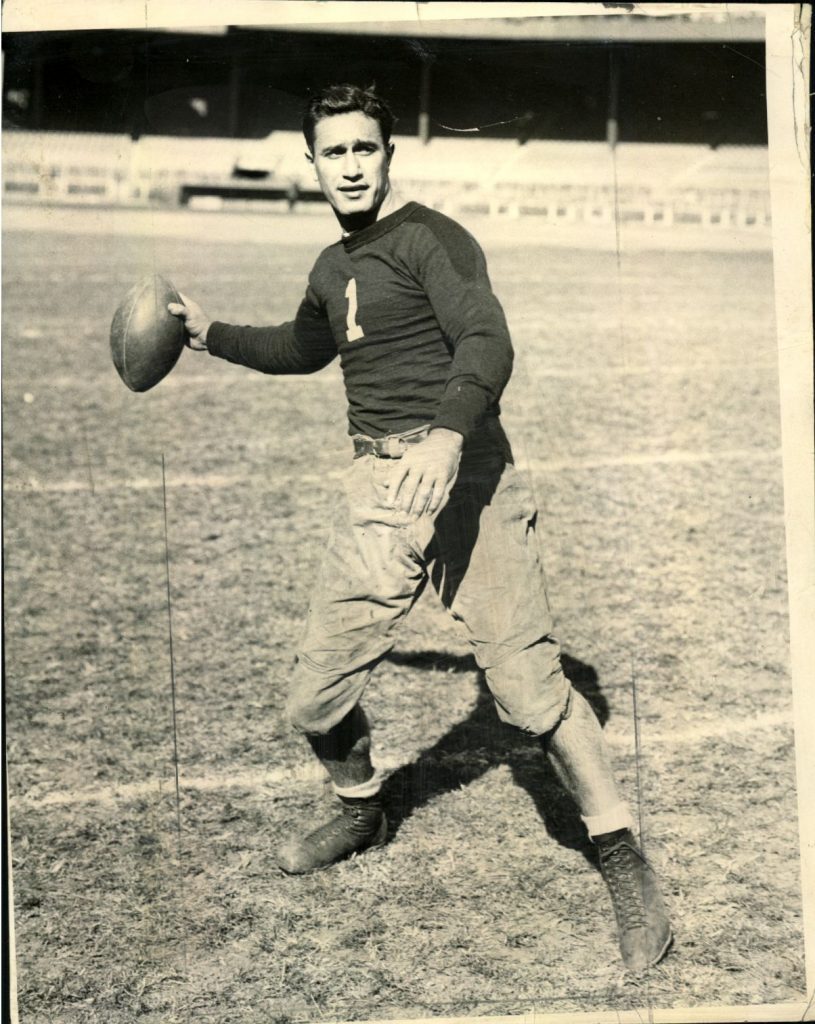

Benny Friedman, New York Giants (1931)

Friedman, whose jersey number with the Giants was #1, immediately turned around the Giants’ fortunes on the football field. From 4-7-2 in 1928, the Giants improved to 13-1-1 in 1929, finishing second in the NFL behind the 12-0-1 Green Bay Packers (NFL Championship Games were not played until 1933). In 1930, Friedman led the Giants to another second-place finish with a 13-4 record (a .765 winning percentage), barely missing out on their second NFL title to the Packers again (who had a .769 winning percentage with a 10-3-1 record).

The biggest event in 1930 for the Giants however was the charity exhibition game played on December 14th at the Polo Grounds against a Notre Dame All-Star team of former Irish football greats, including the legendary “Four Horsemen.” The game was played during the season-long pennant chase with the Packers, but many New Yorkers were starving. Despite New York City being gripped in the depths of the Great Depression, 55,000 fans came to watch and Tim Mara donated the entire gate receipt ($115,153 – an astronomical amount of money in those days) to the New York City Unemployment Fund. It was widely expected by many that the Notre Dame team would beat the Giants, but it was the G-Men who thrashed Knute Rockne’s Fighting Irish 22-0. Notre Dame never crossed midfield and was held to one first down. Friedman, the team captain for the Giants, scored two of New York’s three touchdowns.

“There are those who say Friedman is the greatest passer of all time,” said Rockne. “They are not far wrong. He could hit a dime at 40 yards; besides being a great passer, he hit the line, tackled, blocked, and did everything – no mere specialty man – that a fine football player should do.”

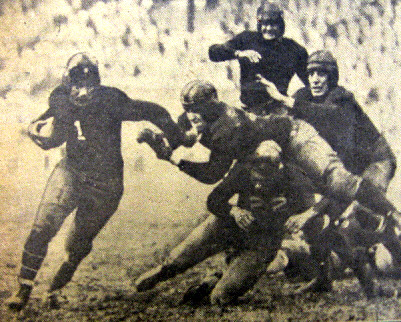

Benny Friedman (1), New York Giants (November 22, 1931)

“He was the best quarterback I ever played against,” said Red Grange. “There was no one his equal in throwing a football in those days.” Grange later said, “Anybody can throw today’s football. You go back to Benny Friedman playing with the New York Giants…He threw that old balloon. Now who’s to tell what Benny Friedman might do with this modern football? He’d probably be the greatest passer that ever lived.”

“He is the greatest forward passer in the history of the game,” wrote a famed New York Daily News sportswriter. “No other passer has his accuracy, his judgment of distance, his intuitive ability to pick out the best receiver.”

Friedman’s productivity in 1931 began to decline. A knee injury slowed him on the field. He also became distracted as he was also serving as an assistant backfield coach at Yale. Indeed, he missed the first four games of the season because of his coaching duties (the Giants lost three of those games). In 1931, the Giants fell to fifth place in the NFL with a 7-6-1 record. After the season, Friedman demanded that Tim Mara give him a piece of the team. “(Mara) said, ‘No, I’m keeping it all for my sons,'” said Friedman. “That was that. I thought I deserved a piece of the club because I felt I had played a big part in moving it from the red ink to the black ink. And when Tim turned me down I felt I should move along, that I couldn’t stay with him.”

In 1932, Friedman left for the Brooklyn (Football) Dodgers as a player and coach. He led the league in completion percentage in his last full season as a player with Brooklyn in 1933, completing 53 percent of his throws or 10 percent better than the next most accuarate quarterback. He was named second-team All-NFL. Friedman retired from the NFL after the 1934 season at the age of 29. In his eight NFL seasons, Friedman played in 81 games, threw 66 touchdown passes, rushed for 18 touchdowns, and kicked two field goals and 71 extra points. He also caught five passes for 67 yards. His 66 career touchdown passes was an NFL record until Hall of Famer Arnie Herber passed him in 1944, the first of his two seasons with the Giants.

After his playing days, Friedman coached the City College of New York until World War II started for the United States in 1941. Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia personally asked Friedman to take the City College position. During the war, Friedman served with the Navy as a lieutenant commander aboard an aircraft carrier. He later became the athletic director (1949-1963) and head coach (1951-1959) at Brandeis University.

The Pro Football Hall of Fame was established in 1963 and Friedman lobbied hard for his inclusion. But by doing so, it is said that he turned off a number of voters. In fact, he was not even nominated from 1963 to 2004. Friedman reportedly became increasingly bitter toward the NFL. In 1970, he criticized the League for “brashness and arrogance beyond belief” for not including pre-1958 players in the NFL’s pension benefit program.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, Friedman was a forgotten man living in obscurity. He suffered from heart problems and severe diabetes, the latter causing him to lose a leg. On November 23, 1982, Friedman turned a gun on himself and died at the age of 77. In the note he left behind, Friedman said he didn’t want to end up as “the old man on the park bench.”

Twenty-three years too late and 71 years after his playing days were over, the Seniors Committee of the Pro Football Hall of Fame finally honored him in 2005.

At the time of Friedman’s selection to the Hall of Fame, Wellington Mara said of Friedman, “He towered over his contemporaries and set the stage of the development of the passing game we see today.”

“Benny revolutionized football,” the Bears’ George Halas once said. “He forced defenses out of the dark ages.”

Sources:

- “Battlin’ Benny – The Man Who Invented the Passing Game,” Lively-Arts.com, Willard Manus, March 2002.

- “The Man That Fame Forgot,” The Boston Globe, January 30, 2005.

- “A Long Wait That Will End Much Too Late,” The Washington Times, Dan Daly, February 5, 2005.

- “Hall of a Snub for Carson,” Giants.com, Michael Eisen, February 5, 2005.

- “Friedman Joining Pro Football’s Pantheon,” ESPN.com, Joe Goldstein, August 2, 2005.

- “Hall of Fame 2005: NFL Pioneer Friedman Headed to Hall Posthumously,” Associated Press, Barry Wilner, August 4, 2005.

- The Giants: From the Polo Grounds to Super Bowl XXI – An Illustrated History, Richard Whittingham, 1987.

- New York Giants: Seventy-Five Years, Jerry Izenberg, 1999.

- New York Giants: 75 Years of Football Memories, edited by Victoria J. Parrillo of The Daily News, 1999.

- Wikipedia.com

- ProFootballHOF.com

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.