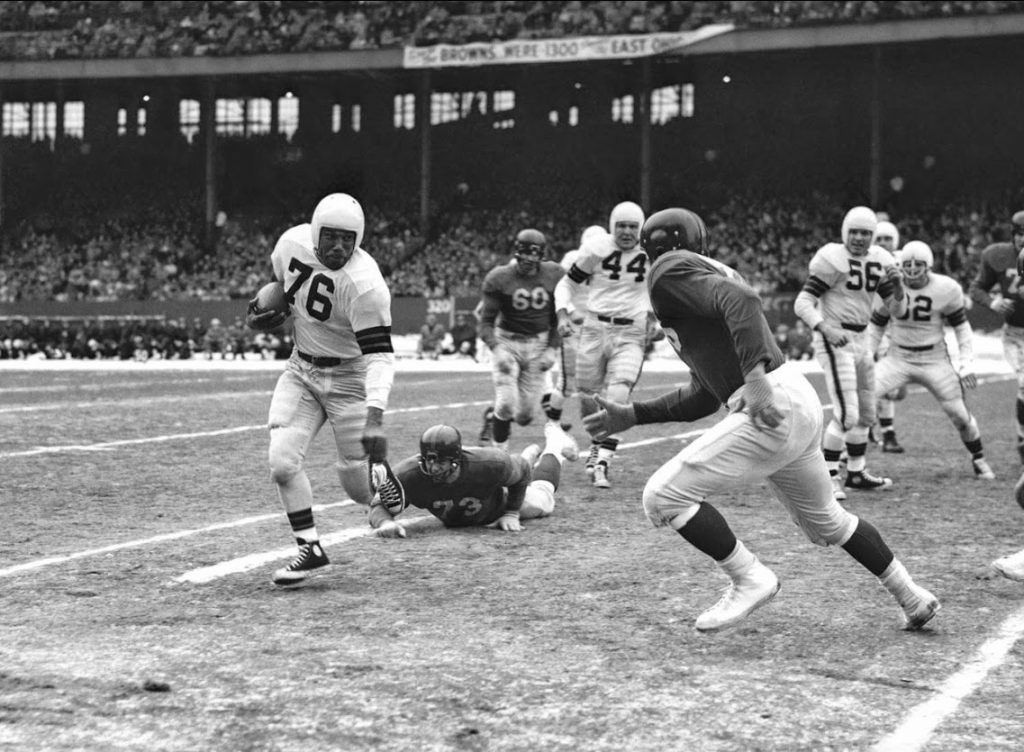

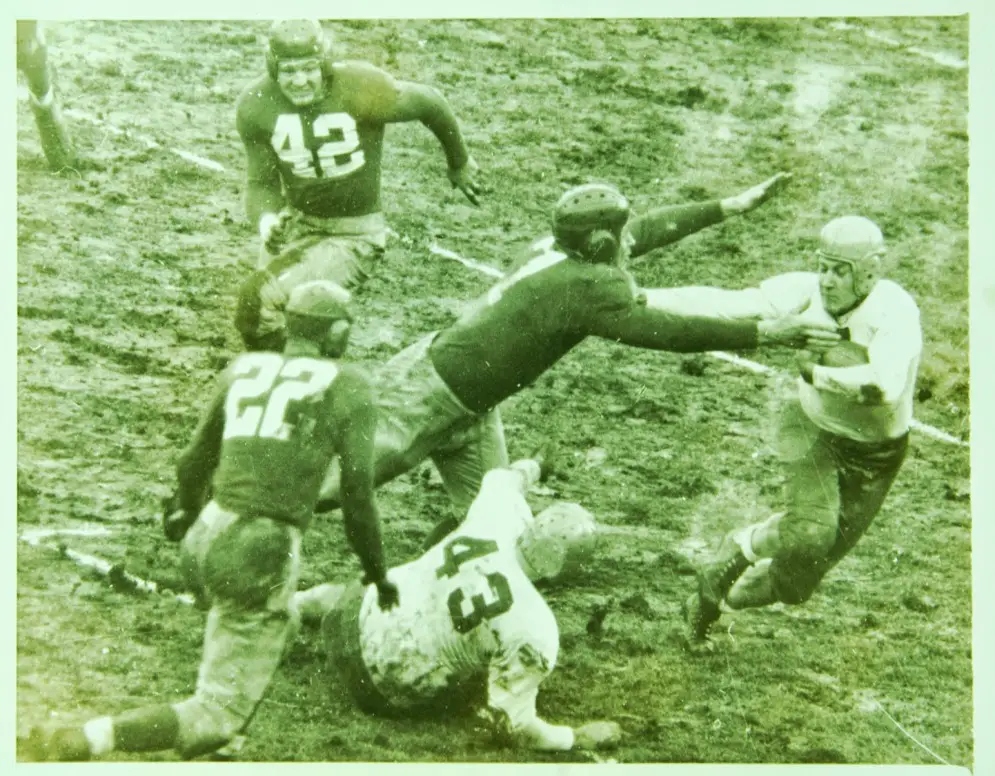

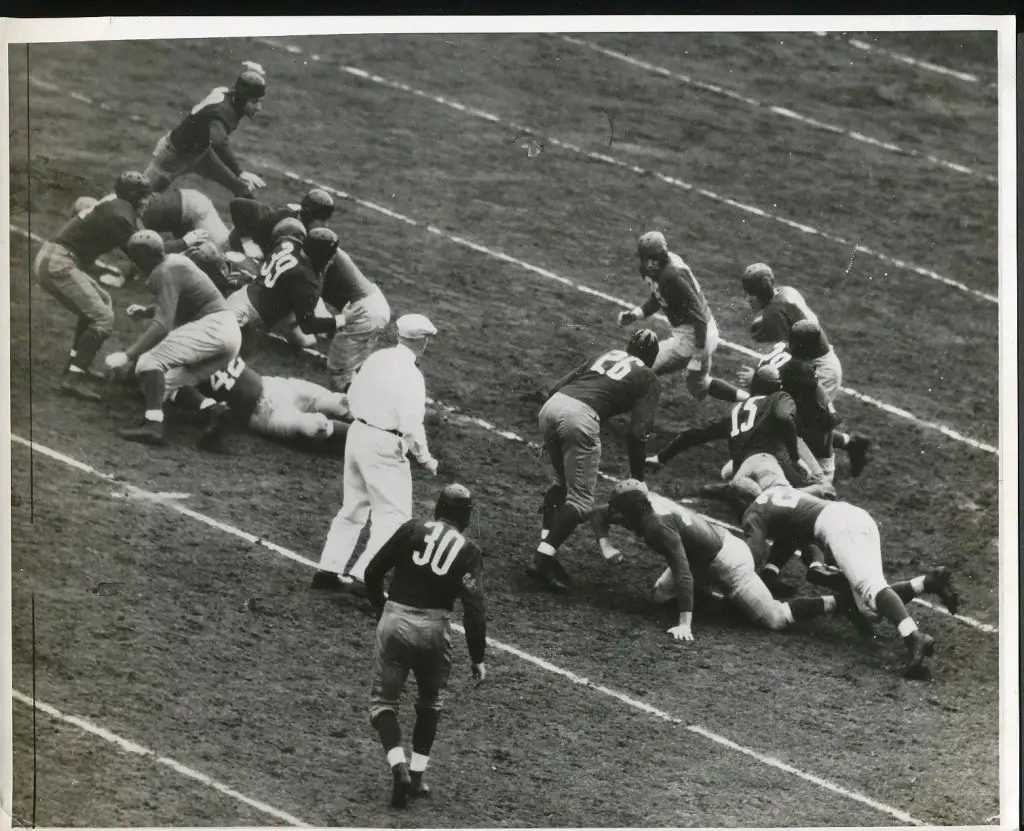

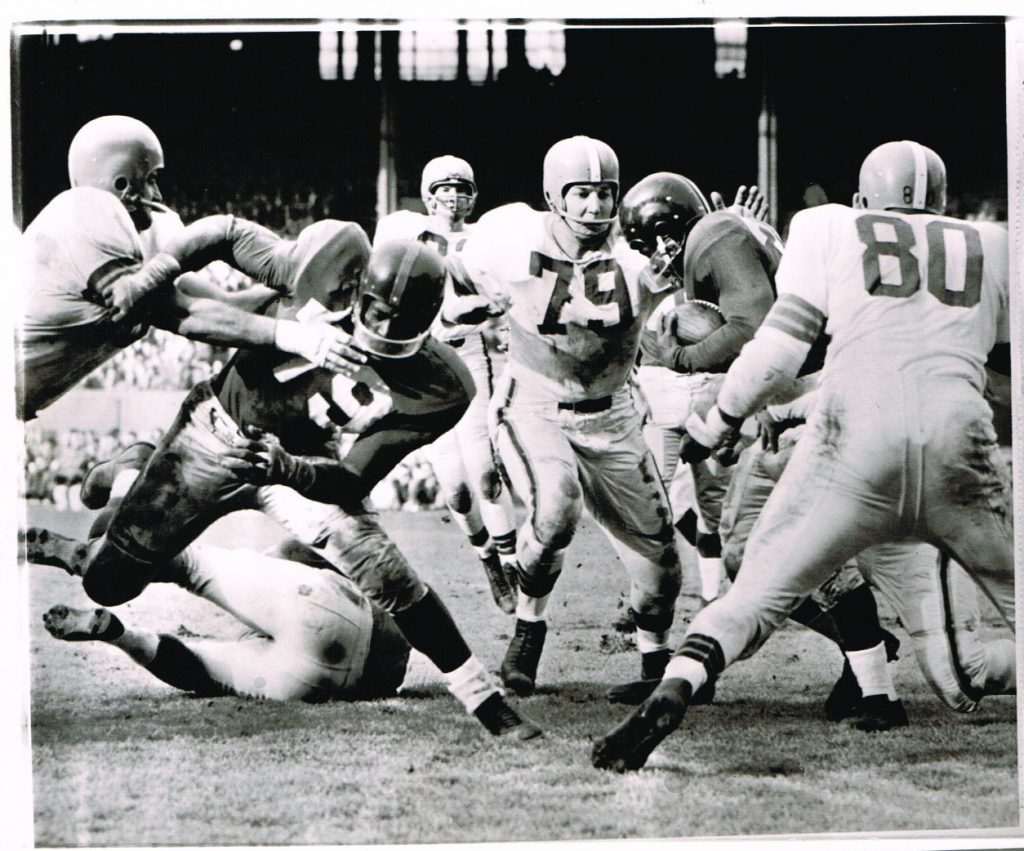

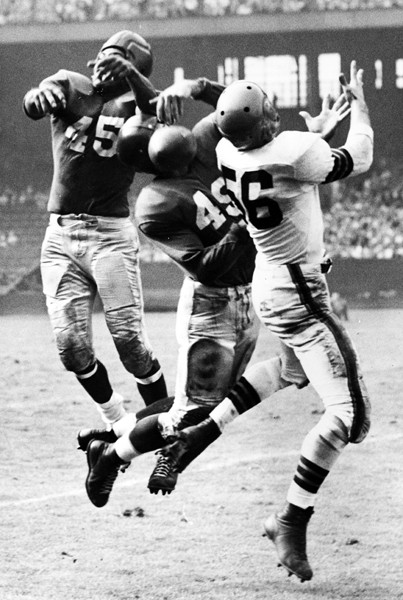

New York Giants at Washington Redskins (September 22, 1940); Tuffy Leemans with the ball.

[contentblock id=1 img=html.png]

Part of the early NFL’s success in distinguishing itself from the more popular college game was splitting the league into two divisions and having the first place finishers meet to decide the league championship. Fan interest spiked, newspaper coverage increased, statistical documentation improved and the league stabilized.

In their eight seasons prior to the divisional format, the New York Giants had two sets of rivals. The first was the teams they regularly competed with for first place, the Green Bay Packers and Chicago Bears. The second set was the various geographical rivals within the New York City area. Most were short lived incarnations: the New York Yankees (1926-1928), the Brooklyn Lions/Horsemen (1927), the Staten Island Stapletons (1929-32), and the Newark Tornadoes (1929-30). The longest-tenured and most-viable franchise was the Brooklyn Dodgers/Tigers (1930-44).

Most of those local teams were unsuccessful and not much of a threat to the Giants on the field, but they were more than a nuisance. They competed with the Giants for talent and occasionally were successful in outbidding the established franchise for players. They also were an unneeded distraction when home dates conflicted. It was hard enough getting fans to come to the Polo Grounds without having games coincide within the city limits.

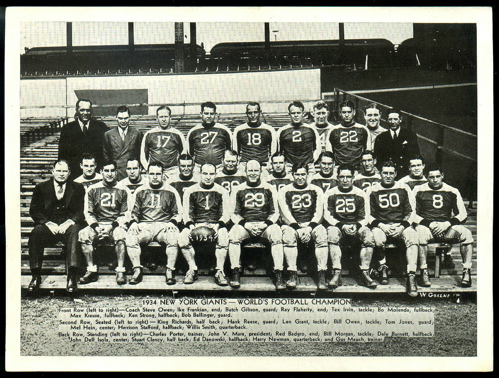

At the outset of divisional play in 1933, the usual teams were at the top. The Giants won the Eastern Division title and the Bears won the Western. In fact, over the first 14 seasons of this format, there was very little variety in the NFL Championship game. The Western Division was represented by the Bears eight times, the Packers four times and the Detroit Lions and Cleveland Rams once each. The domination in the East was even more stringent; all 14 titles belonged to just two teams. The Giants represented the East eight times and the other six by their first true rival, the Boston/Washington Redskins.

The 1933-35 seasons saw the Giants dominate the Eastern Division with little competition. Although New York’s record against Boston was 5-1 in that span, the rivalry with the Redskins grew to be so spectacular in the late 1930’s through the mid 1940’s that it was compared to famed college clashes in the vein of Yale-Harvard and Army-Navy. The league schedule-makers wisely capitalized on this feud, and often scheduled the Giants and Redskins to meet in the final week of the regular season. The December Giants-Redskins games at the Polo Grounds regularly had larger crowds than their Championship Games against the Bears or Packers the following week. The Redskins final season in Boston was the launch point, and it featured what would become almost an annual rite of passage to the Championship match – a winner-take-all, head-to-head season finale.

The New Contender Emerges

In 1936, former Giant end Ray Flaherty, who served as Steve Owen’s assistant coach in 1935, was in his first season as head coach of Boston and he had his team playing sharply, physically and confidently. Joining Flaherty was rookie Wayne Millner, a strong two-way end who proved to be a clutch receiver. The Redskins arrived in New York with a 6-5 record while the Giants stood at 5-5-1, which included a 7-0 win at Boston in October. Only a victory would vault the Giants into first place.

Much of the hype leading up to the game included a subplot of who would lead the NFL in rushing. Giants’ rookie sensation Tuffy Leemans entered the final week with 806 yards. New York’s practices were shortened in the early part of the week, first due to the Polo Grounds field being frozen, later from torrential rains falling. One of the practice reports from midweek described the scene of the Giants sloughing through ankle-deep mud in the patch of field close to the center field bleachers, as the grounds crew had the field of play covered with a tarp. “The ball carriers slipped and passes found the water-soaked pigskin wobbling through the air.”

The weather was not much better on game day, and kept what was expected to be a near capacity crowd to 18,000. The New York Times described the contest as not “even being a football game, but rather a parody of one.” Ball carriers “skidded as far as they ran” in “the clammiest mud imaginable.” The downpour lasted through the first three quarters and floodlights were turned on in the second half to illuminate the mud caked players through the foggy haze that settled inside the dreary Polo Grounds. The pileups became dangerous as the field deteriorated. The hazardous conditions were blamed for Les Corzine’s broken ankle and Tony Sarausky’s concussion “that narrowly missed being a fracture of the skull.”

The Redskins put the Giants in a hole early and held the field-position advantage throughout. Future Hall of Fame tackle Glen “Turk” Edwards partially blocked Ed Danowksi’s punt from the Giants end zone, setting up Boston on the New York four-yard line. Three plays later Don Irwin plunged over from one-yard out to put the Redskins ahead 7-0.

Boston Redskins at New York Giants (December 6, 1936)

New York’s offense never found any tread. Passing the ball was a near impossibility, and Boston played a virtual 10-man line to clog the line of scrimmage and stuff the New York rushing attack in the “veritable quagmire.” Boston threatened twice more in the first half, but failed to capitalize as their scoring chances failed with a missed a field goal and lost fumble. Battles’ 74-yard sloshing punt return in the third quarter sealed the Giants fate.

Ironically, despite the Giants 14-0 loss, the Polo Grounds would still host the NFL Championship Game the following Sunday. Redskins Owner George Preston Marshall was dissatisfied with the small crowds at Fenway Park and decided his team would not return to Boston. Green Bay defeated the Redskins 21-6 in a defensive slugfest. After the game, Marshall told his team (which had three All-Pros in Battles, Edwards and center Frank Bausch) they were good enough to win a championship, all they needed was a quality passer.

That passer was taken with the Redskins first pick of the draft: tailback Sammy Baugh, whom Marshall personally scouted. Baugh was more than a ground breaking passer, he was an all-round player who also was a hard tackling safety on defense and exceptional punter. Meanwhile, Owen and the Giants believed they were more than one player away from going back to the Championship Game, and populated their roster with a significant number of rookies, including backs Ward Cuff and Hank Soar, ends Will Walls, Jim Poole and Jim Lee Howell, and guard Orville Tuttle.

In 1937, the new-look teams met under the flood lights for a night contest in front of 25,000 Washingtonians. They marveled at Baugh’s aerials, which twice drove the home team to field goals. The real ace for the Redskins though was back Riley Smith, who not only accounted for all of Washington’s points in the 13-3 victory, but who also made the game-altering play on defense. New York trailed 6-3 in the fourth quarter and was advancing on Washington’s rugged defense. Twice earlier, New York had been stopped on downs in goal-to-go situations. Riley intercepted Danowski’s pass and returned it 58 yards for the clinching score.

Despite the loss, Owen had to be encouraged with his young team’s performance on a big stage against one of the best outfits in the league. New York actually had the statistical advantage in most categories, including a lop-sided rushing-yards advantage of 226-105. The teams were almost even in the forward passing department. Baugh was 11-17 for 116 yards and Danowski 9-17 for 85 yards, but Danowski threw two interceptions, the second of which being the most costly.

Busy at the Blackboard

New York won their next four games and entered the season finale with a 6-2-2 record. Part of their success was a new two-platoon system where Owen had his team divided into interchangeable sub units. Beginning with the home opener in October versus Philadelphia, Owen swapped out 10 players at the end of the first and third quarters – the lone exception being Mel Hein who usually played the full 60 minutes. Not only did this keep his team fresh, it gave all the young players plenty of game experience.

A friendly rivalry known as “the soda pop derby” developed between the two squads (known as Team A and Team B) and they charted their net score throughout the season. The team with the highest net point differential would be treated to a round of sodas (or perhaps a more adult beverage) by the other.

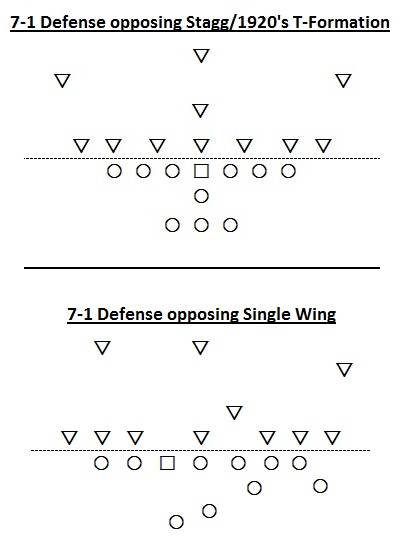

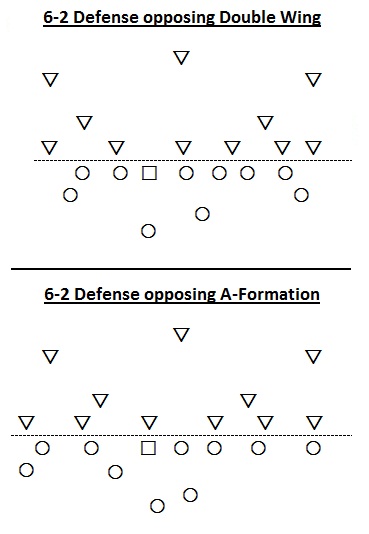

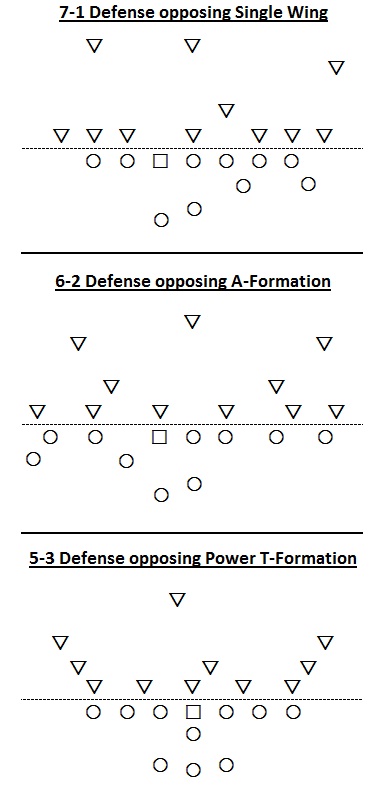

The 7-3 Redskins won five of six following a 2-2 start. Rookie Baugh hit his stride in mid-October and led the league in forward completions and passing yards. He was most comfortable operating from the Double Wing formation. This formation featured the Single Wing’s unbalanced line, but had the quarterback or blocking back moved just outside the end, potentially giving the tailback four receiving options on every snap. Since the backfield was more balanced in this setup, the defense had a more difficult time anticipating where the ball would go after the snap. Flaherty also devised a new strategy where a back moved laterally to receive a pass behind a group of pulling linemen, which would later become known as a screen pass. Washington also featured the league’s #1 defense and leading rusher, Battles, who became the first player to lead the league in rushing twice (having first done so in 1932.)

The Giants-Washington game at the Polo Grounds again fell on the final Sunday of the regular-season schedule and would determine which team played the Western Division Champion for the Ed Thorp Memorial Trophy. The anticipation was high and ticket demand heavy – the Giants had hopes for a sellout. Marshall did his part to drum up interest in his own pompous way. He brought a caravan of approximately 10,000 football crazy fanatics from the DC region north on the Amtrak to Manhattan, including the Redskins 75-piece matching band, who paraded from Penn Station to the Giants offices at Columbus Circle. New York had never seen anything like it.

The Giants-Washington game at the Polo Grounds again fell on the final Sunday of the regular-season schedule and would determine which team played the Western Division Champion for the Ed Thorp Memorial Trophy. The anticipation was high and ticket demand heavy – the Giants had hopes for a sellout. Marshall did his part to drum up interest in his own pompous way. He brought a caravan of approximately 10,000 football crazy fanatics from the DC region north on the Amtrak to Manhattan, including the Redskins 75-piece matching band, who paraded from Penn Station to the Giants offices at Columbus Circle. New York had never seen anything like it.

The Redskins boasted of being at both psychological and physical peaks for the December showdown, not a man on their roster missed practice. The press highlighted the fact that Flaherty held a 2-1 advantage against his mentor Owen. The Giants had several key personnel nursing injuries, including Leemans, but had a statistical advantage in the standings. New York would be awarded first place in the event of a tie. Owen was also ready to fully deploy a scheme he’d been experimenting with throughout the season – a twist on the Single Wing that he called the A-Formation.

The A-Formation had three aspects that made it unique:

- First, the line was unbalanced to one side and the backfield strong to the opposite side. The Single Wing was a power formation that attacked the edges of the defense with slant runs. The line and backfield were always strong to the same side, having the intent of delivering the most men to the point-of-attack as possible. The A-Formation’s asymmetry offered more opportunity for deception.

- Second, the line splits were very unusual. The ends were moved a few yards further way from the tackles (a tactic Owen no doubt observed in November when the Giants hosted Green Bay, as Earl “Curly” Lambeau moved end Don Hutson further away from the collisions at the line of scrimmage to take advantage of his speed and route running ability) and spread the defense laterally. The over and under guards were close to Hein at center, but the right tackle took a wider split, almost as an end would. This created natural running and passing lanes and caused confusion in the defense’s pre-snap alignment.

- Third, Hein was the multi-talented catalyst for the execution. His unique combination of range and strength allowed the line to deploy in this unorthodox manner. No other center possessed the capability of snapping the ball (Hein was the only center at the time to snap with his head up looking at the defense), getting out of his stance and engaging a defender effectively. Every man in the backfield was eligible to take the snap. In Single Wing and Double Wing schemes, the snap almost always went to the tailback. In the A-Formation, Hein would snap the ball to the tailback, halfback or fullback on any given play. Not only did the defense have little idea where the play would be going, they did not know from where it would originate. Being a highly-regarded defensive strategist throughout his career, Owen’s offensive system was derived from the places that gave defenses the most trouble, uncertainty and hesitation.

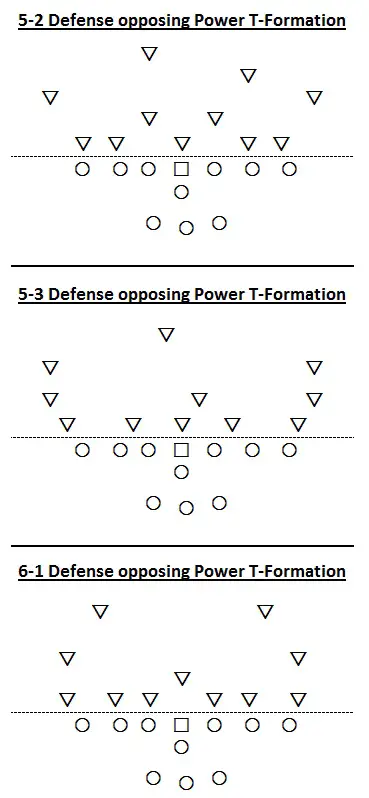

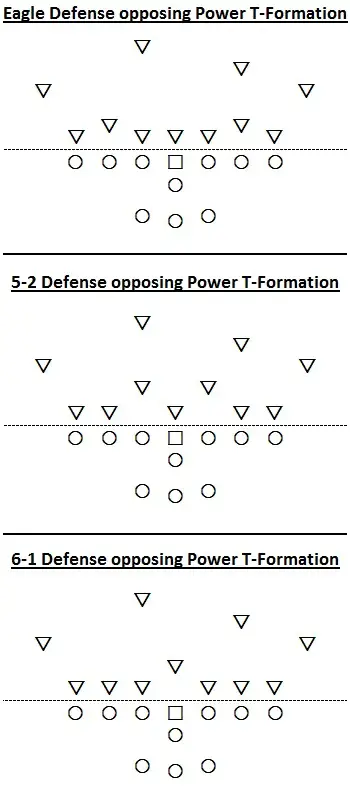

New York would also prepare with a new defensive alignment to deal with Baugh’s aerial assault: a 5-3-2-1 defense instead of their usual 6-4-1. The Giants practices were lively and the team brimmed with confidence. They had extra time to prepare as their last game was against Brooklyn on Thanksgiving Day (a disappointing 13-13 tie, a win would have clinched the East.) A case of beer was present at the Sunday practice as players were ready to celebrate the anticipated Green Bay victory over Washington. When word spread that the Redskins upset the Packers 14-6, guard Johnny Dell Isola told Owen, “Don’t let that bother you Steve. We’ll get that championship for you next Sunday anyway.”

New York would also prepare with a new defensive alignment to deal with Baugh’s aerial assault: a 5-3-2-1 defense instead of their usual 6-4-1. The Giants practices were lively and the team brimmed with confidence. They had extra time to prepare as their last game was against Brooklyn on Thanksgiving Day (a disappointing 13-13 tie, a win would have clinched the East.) A case of beer was present at the Sunday practice as players were ready to celebrate the anticipated Green Bay victory over Washington. When word spread that the Redskins upset the Packers 14-6, guard Johnny Dell Isola told Owen, “Don’t let that bother you Steve. We’ll get that championship for you next Sunday anyway.”

Despite all the preparation, conceptualization and scheming, football games are decided on the field of play. The second largest crowd in pro football history to that point, 58,285, witnessed a masterful performance by the visitors. The New York Times described the scene eloquently: “There is not a superlative in the English langue that can quite describe the magnificence of the Washingtonians. Their charging had the New Yorkers rocked back on their heels, their passing had them absolutely bewildered and the running was a gem of football perfection.”

Despite all Owens best intentions, the Redskins were clearly the better team, and dominated the game 49-14. Although the Giants passers actually accrued more yards than Baugh, they were far less efficient. Baugh was 12-of-17 for 212 yards, 1 touchdown, and 1 interception while the Giants combined for 18-of-33 for 154 yards, 2 touchdowns, and 2 interceptions. The real story of the domination was told in the trenches. Edwards and his crew were powerful along both fronts. Washington outrushed New York 238-18, including -5 for the Giants in the second half. Battles had 165 yards rushing and also a 75-yard interception return.

The Redskins caravan traveled to Chicago, where they upset the favored Bears at frozen Wrigley Field in 15 degree temperatures, 28-21, to win the NFL Championship.

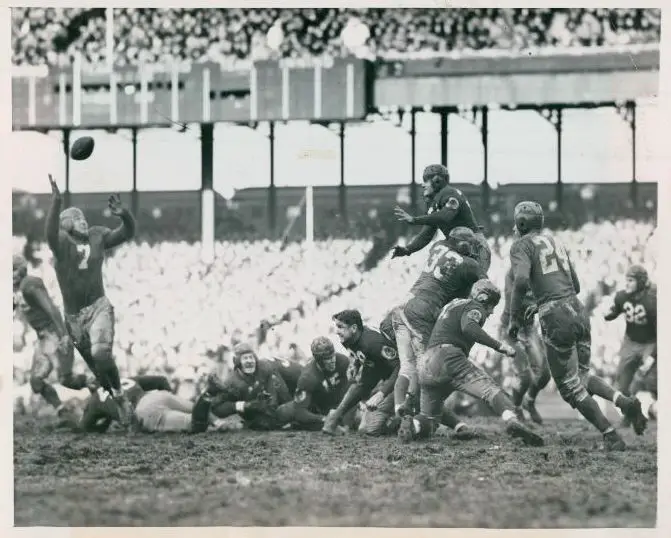

The Giants exacted revenge on their new favorite team to hate in 1938. New York upset the Redskins in Washington 10-7 in a fourth-quarter comeback in October, then throttled them 36-0 in the season finale at the Polo Grounds. The Giants defeated Green Bay 23-17 for the NFL Title the following week.

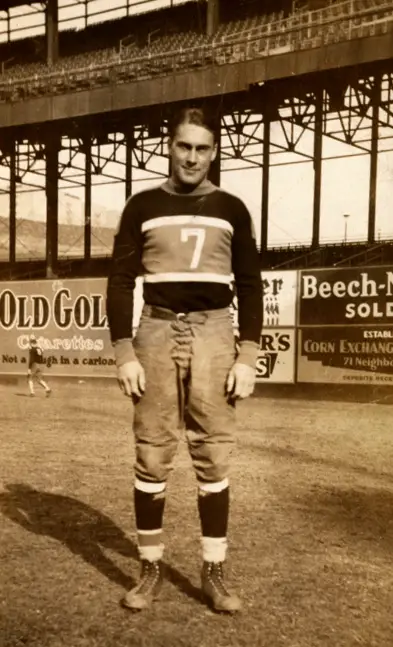

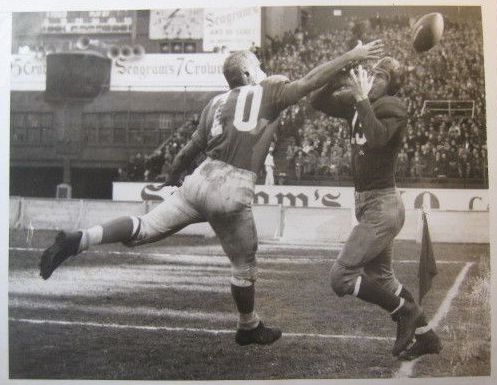

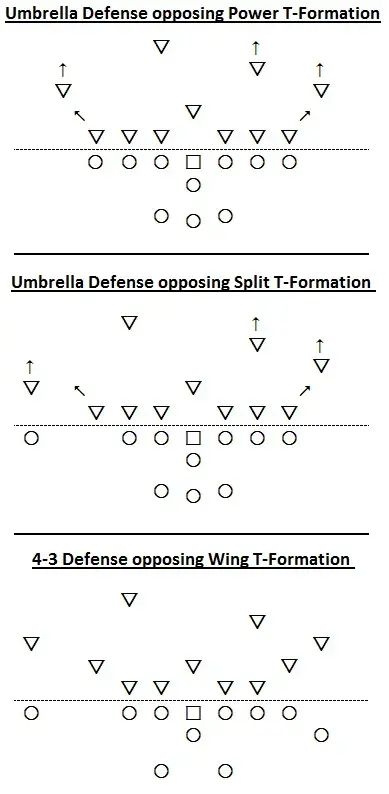

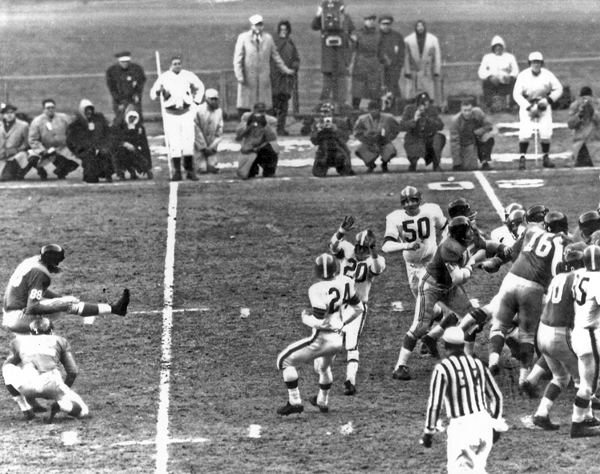

Washington Redskins at New York Giants (December 4, 1938); Mel Hein (#7)

(See “The 1938 New York Giants” for more detail.)

In 1939, the meeting of the NFL’s previous two champions took place at Griffith Stadium in the first week of October. Both teams were 1-0, with wins over Philadelphia (Washington entered the game on a week’s rest) and New York was riding a 10-game unbeaten streak that had begun with the fourth quarter come-from-behind victory over the Redskins the previous year. This game would be played without one of the heroes of that win, end Jim Lee Howell was sidelined with an injury, as well as Leemans, Soar and guard Tarzan White.

The anticipated capacity crowd was held to 26,341 by driving rains that turned the field “into a miniature lake,” but they were treated to a primal battle featuring “bone shattering line play” as described in The New York Times. The Giants defense kept New York’s unbeaten string to eleven games with opportunistic play, as Washington controlled the field position and the ball throughout. The Redskins had the advantage in first downs 12-7 and total yards 208-74 (the Giants had -3 yards passing.) Three interceptions, a fumble recovery and a goal-line stand resulting in a missed 15-yard field goal by Washington enabled the Giants to survive with a 0-0 tie.

Ascending Tension

New York continued clutch play throughout the season. They did not usually dominate, but big plays at key moments earned them the moniker of “money team.” At 8-1-1 entering the season finale, the Giants only blemish was an 18-14 loss at Detroit in November. Washington was equally impressive and also 8-1-1. Their only loss was a 24-14 setback to the Packers, who had already clinched the Western Division. Both teams were confident, and the demand for tickets was so strong 4,000 bleacher seats were installed at the Polo Grounds. The Redskins were expected to arrive with approximately 15,000 in tow.

An interesting development from Washington this season was the addition of tailback Frank Filchock to their roster. While Filchock favored running, he was very capable throwing the ball and at times performed as a near equal with Baugh. “We made the defenses change,” Flaherty explains. “They’d get all set for Baugh’s passing and then would have to change when we put the running unit in. We tried to keep them constantly off balance and usually succeeded.” Filchock not only led the NFL in scoring strikes in 1939 with 11, he also earned the distinction of throwing the first 99-yard touchdown in NFL history (to Andy Farkas at Pittsburgh.) Balancing out the throwing tandem of Slingin’ Sammy and Flingin’ Frank, as they were known as in Washington, was fullback Farkas leading the league in scoring with 68 points (five rushing touchdowns, five receiving touchdowns, a kickoff return touchdown and two point afters.)

The Giants clutch defense would be put to the test. New York led the league in key categories of fewest points surrendered and most takeaways, and was second in yards yielded. Most of the Giants were in good health, save for Leemans who continued to nurse nagging injuries that he tried to keep discreet, “I’m not going to let them know where I’m banged up. They’ll have to find that out themselves.”

Refusing to take a cue from his boastful owner Marshall, Washington coach Flaherty only predicted “a good, close game.” Owen was equally guarded, “We’ve got a tough ballgame ahead of us. The boys are ready for it and I know they’ll do their best. That is all.” In the event of a tie, a playoff would be held the following Sunday in Washington.

The weather was not ideal. A chilly rain fell and the field was somewhat muddy, but would hold up well. The crowd of 62,530 jammed into the Polo Grounds was the second largest in NFL history to that point (the largest was the Red Grange at the Polo Grounds in 1925 that exceeded 70,000) and they were treated to an intense, thrilling contest that ended with a legendary controversy.

The Giants dominated the first 30 minutes. Their physical play limited Washington to four rushing yards and sent several key Redskins to the sidelines with injuries, including Baugh, Farkas and Edwards. Despite their dominance, the lead was just six, coming on Cuff and Strong field goal placements. Washington’s lone drive into New York territory ended with a Leemans’ interception of a Filchock pass in the end zone just before the half.

While the Redskins offense remained in capable hands with Filchock, Baugh was missed in the punting game. A poor third quarter punt set the Giants up with a short field at the Washington 40-yard line. After Danowski completed a pass Soar, two rushes placed the ball on the 16-yard line. The drive stalled and New York came up empty when Cuff’s 21-yard field goal attempt missed. The Giants came right back. Soar intercepted Filchock and returned the ball 25 yards to the Redskin 19-yard line. Washington’s defense was stout again, but this time Cuff’s 15-yard placement was good. New York led 9-0 going into the fourth quarter.

Filchock led Washington on their first advance of the second half, but New York put the threat to a close when Leemans, on his bad leg, intercepted his second pass of the afternoon. Washington held and forced a New York punt. The Giants intercepted another Filchock pass, but it was the Redskins who were about to alter the tenor of the contest. They held New York again. Then Willie Wilkin blocked Len Barnum’s punt, giving Washington possession on the Giants’ 19-yard line with hope and a jolt of momentum.

After a run lost a yard, Filchock went back to the aerial attack. Fading to his right as he dropped back, Filchock launched a high arcing long ball to the left, which was timed perfectly to miss being deflected by the diving Barnum into the hands of Masterson just across the goal line. Masterson added the point-after and Washington was very much alive, trailing 9-7 with 5:34 on the clock.

Detonation

The rejuvenated Washington defense held the Giants to another three-and-out. Dick Todd returned the punt 30 yards to the New York 47-yard line. Filchock and Todd each advanced the ball once while their line creased New York’s forward wall. On first and ten from the Giants 19-yard line, Filchock completed a pass to Frank Spirida inside the eight-yard line. Filchock ran a keeper to the five and Washington called time out with 45 seconds left. Flaherty was penalized for calling consecutive time outs as he sent Bo Russell out for the placement attempt and the ball was moved back to the 10-yard line. Those five yards would prove to be critical.

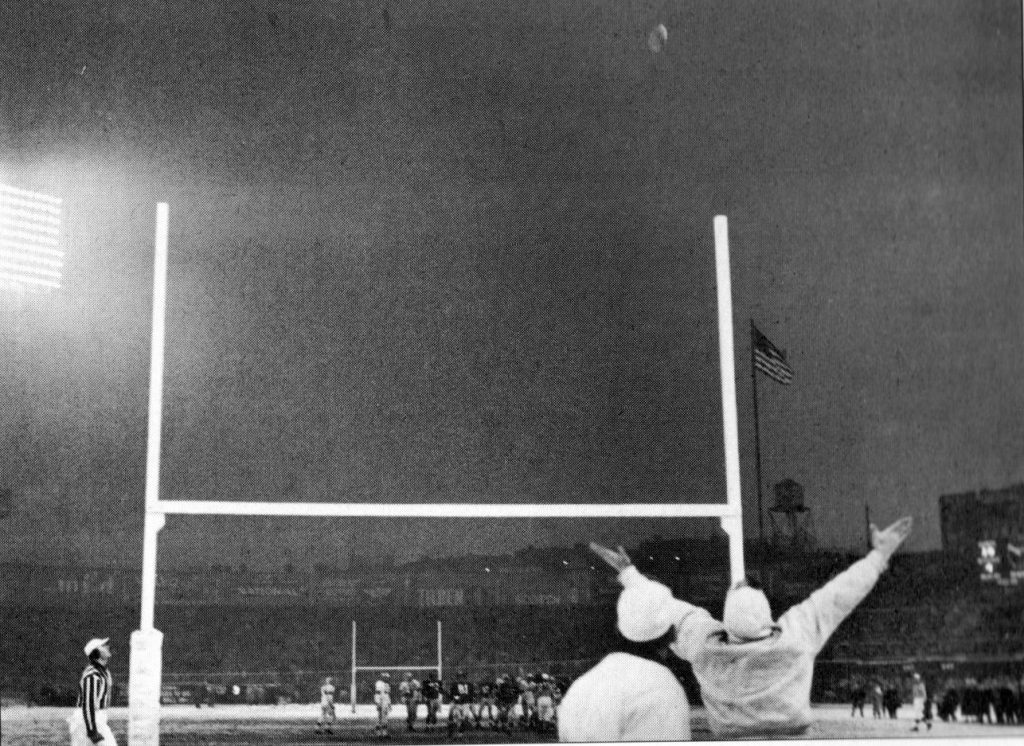

There were no hash marks visible on the field to judge where the ball was spotted, but the spot was right-of-center, and Russell’s straight-ahead kick from short range went up in a straight line and appeared to pass almost directly over the right upright. It is impossible to tell with any degree of certainty whether or not it was inside, as the goalposts were much shorter in this era. The ball cleared the field of play and landed in the Polo Grounds grandstand. It appeared to have traveled a diagonal line of trajectory, but the possibility remains that it may have been just good enough.

The fans in the end zone seats celebrated as the ball landed among them while some of the Washington players also celebrated on the field. The mood changed dramatically as referee Bill Halloran walked into the middle of the players, waving his arms indicating the kick was no good. Several Redskins players stomped behind Halloran who conferred with umpire Tom Thorp. Players and coaches from the Washington sideline swarmed around the officials.

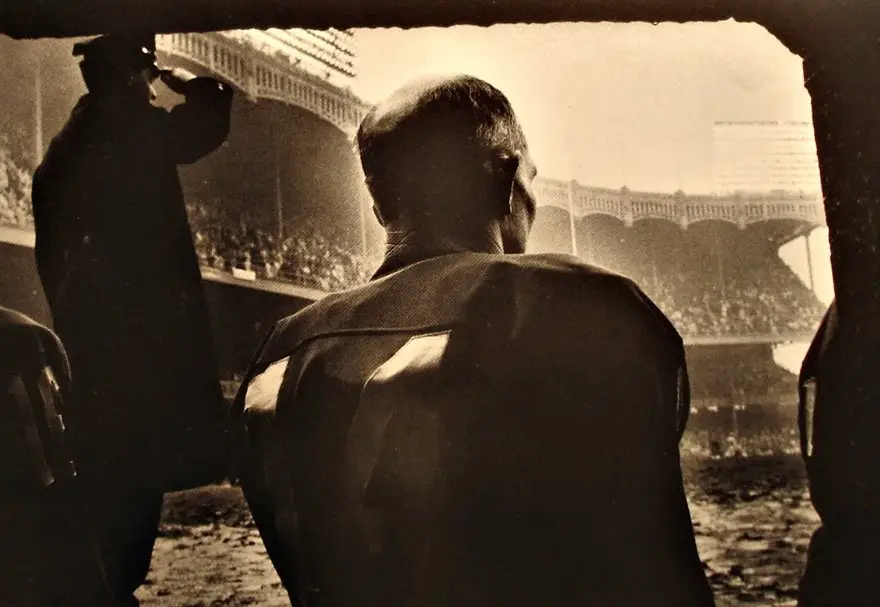

Order was restored long enough for Danowski to twice hand off to John “Bull” Karcis, who was assaulted by enraged defenders each time he went into the line, and run the remaining time off of the clock. When the final gun sounded, seemingly every man from the Redskins sideline went right for Halloran while Giants fans stormed the north end zone and dismantled the goal posts. A mob of Washington players allegedly threatened Halloran and Thorp who were surrounded by police and Polo Grounds ushers, while the enraged Flaherty gesticulated that the kick was good. Wingback Ed Justice was alleged to have thrown several punches at Halloran (without any landing) and was dragged off of the field by several officers. The scene was riotous, brawls broke out amongst the horde of fans running rampant on the field, while the argumentative mob followed the officials into the tunnel toward the dressing rooms. It was a full half hour before the Polo Grounds was settled again.

Several spectators stated the kick was wide – by anywhere from two feet to a few inches – while in the locker room Washington players insisted it was good. In the post-game press conference, Flaherty seethed, “If that Halloran has a conscience, he’ll never have a sound night’s sleep again.” The kicker Russell himself said, “It was close; it could’ve been called either way.” Most surprising was the refusal to comment from owner Marshall.

The day after the game, NFL President Carl Storck revealed that if an investigation revealed Justice had thrown a punch he would be banned from the league for life, “If Justice was guilty of attacking an official, as has been alleged, he is deserving of the most serious penalty we can impose. Our officials must be protected.” Justice was ultimately exonerated and played with Washington through the 1942 season. Regarding the field goal decision, Storck said, “The decision on a play of that type must rest entirely on the referee’s judgment, and I have every confidence in Bill Halloran’s judgment. He is highly competent.”

At the press conference opening championship week, Owen said, “I was in no position to see whether it was good or not. No one on the sideline is in a position to see. Bill Halloran never hesitated in giving his decision.” The Giants went on to play the Packers in Milwaukee for the NFL title but were handled ruthlessly in a 27-0 rout.

The 1940 season saw the emergence of a new contender in the East. The young Brooklyn Dodgers with their star tailback Clarence “Ace” Parker found themselves on equal footing with the two dominant teams. New head coach Jock Sutherland had them operating an efficient, and at times explosive, offense and rugged defense. They were no longer a team to be taken for granted as an easy win.

Washington Redskins at New York Giants (November 24, 1940)

While the Giants and Redskins split a pair of 21-7 home wins between one another, the Dodgers handed New York a 21-6 defeat at the Polo Grounds on December 1, burying the Giants in third place, their lowest finish in four years. It was their first loss to Brooklyn since 1930, ending a 17-0-3 unbeaten run versus their inter-borough rivals. Despite leading the NFL is scoring during the regular season (and forging the distinction of being the last Wing-style team to do so) Washington found out firsthand what the future of the professional football was going to look like when the Chicago Bears unleashed George Halas’ new version of the T-Formation. The final score of 73-0 remains the most one sided score in NFL history.

A Period of Perseverance

In 1941, the Giants swept Washington, including the second game where the Giants scored 10 points in the final 53 seconds for a come-from-behind win at the Polo Grounds to clinch the Eastern Division. The Dodgers, however, swept the Giants, including the game on December 7th when a chill went through the crowd as the PA called upon all active duty servicemen report immediately for duty. Nobody knew at the time that Japan had just attacked the U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor. Brooklyn’s victory also knocked the Redskins into third place. New York played an anti-climactic championship game in front of a small crowd at Wrigley Field against the Chicago Bears the next week. The Monsters of the Midway gave New York their own dose of the modern T-Formation and won the game 37-9.

By the time the 1942 training camps rolled around, the NFL landscape was very different. The most able bodied young men were called to duty in service of their country. Young men from college who were deemed undesirable for service mixed with aged veterans coaxed out of retirement, including Hein.

The Giants opened their season at 1-0 Washington in one of the most peculiar and unexpectedly significant outcomes in NFL history. The game conditions were miserable: blustery winds, heavy rain and a muddy field. The Giants won the coin toss and the normally conservative Owen elected to receive (he was the first coach to ever win the toss then elect to kick, being more comfortable with his defense to open a game). The first play from scrimmage was a 30-yard pass from Leemans to end Will Walls, who caught the ball at the 20, evaded a defender and sloshed his way into the end zone for a surprising 7-0 lead. Owen said later, “When the game opened, it seemed sure to rain, and I instructed Tuffy Leemans to try for a touchdown pass as soon as he got the ball.” That was New York’s only pass attempt of the game. The Giants were seemingly comfortable with the touchdown lead and content to run into the line a few times before punting and playing defense.

Baugh’s short passing game worked fairly well given the conditions. Several completions moved his team to the Giants 5-yard line where halfback Bob Seymour would go over for the score on his second plunge. Despite controlling the ball and amassing a huge advantage in yardage – Washington would end up outrushing New York 113-1 – the game remained deadlocked 7-7 late into the third quarter. Owen rolled the dice a second time and adjusted his defensive backfield during a Redskin advance. O’Neal Adams snared a Dick Poillon pass and returned it 66 yards for a touchdown to give the Giants a 14-7 advantage. It was a lead that would hold up, despite the Giants inability to register a single first down over the game’s 60 minutes. [Note: In modern scoring a touchdown is recorded as a first down.]A final Washington drive ended with another interception in New York territory in the fourth quarter.

The final statistics belied logic. Washington’s advantages of 15 first downs to 0 and 233 total yards to 51 left seemingly intelligent observers flummoxed. Members of the press corps credited the Giants with playing “smart football,” noting New York did win the turnover battle 3-0. Owen said of the game changing Adams interception, “That was not luck; we had gambled on stealing a favorite play of the Redskins, a wide flat pass, and had our ends play inside their ends.” New York’s strong punting game also served them well, as they forced Washington to drive long distances on the soft, muddy Griffith Stadium field. Marshall remained incredulous however: “One yard! Gadzooks, I could make more yardage than that just by falling down!”

Marshall was likely placated by the rest of Washington’s dominant season. This proved to be the Redskins lone loss of the campaign as they were hardly tested the remainder of the season. The roll to a 10-1 record included a 14-7 win at the Polo Grounds in November. The Giants meanwhile had a mediocre 5-5-1 year, only good enough for third in the East. The Redskins hosted the most impressive Bears team of the period for the NFL Championship. Chicago led the NFL in total offense and defense while boasting an average margin of victory that was nearly 27 points (one of those wins was a 26-7 decision over the Giants at the Polo Grounds) despite having lost Halas to the Navy mid-season (Hunk Anderson and Luke Johnsos served as co-coaches for the final six games ).

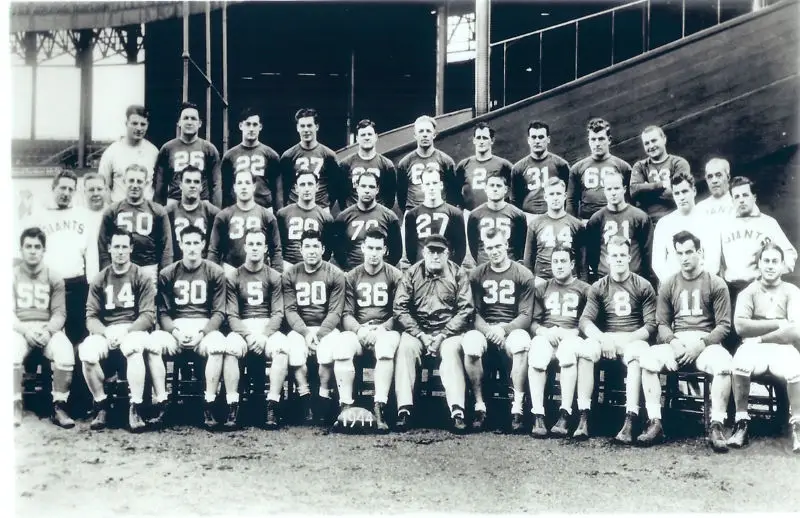

Washington Redskins at New York Giants (November 15, 1942)

Baugh, and the other Washington players who were embarrassed two years earlier, earned a semblance of revenge as they deprived the Bears of a perfect season in a 14-6 upset. The end result, given the Giants unlikely September victory, was that the NFL would have to wait another 30 years before it would see a perfect team, when Don Shula’s 1972 Dolphins emerged 17-0 after beating George Allen’s Redskins in Super Bowl VII.

Reinvigorated Competition

In 1943, the manpower drain from World War II forced the NFL to trim roster size, shorten the season schedule and loosen restrictions on in-game substitution to allow coaches game management flexibility. Cleveland lost its team for the season, as the league granted the Rams request to suspend operations for a year as they had lost too many players as well as their owner to the armed services. Washington lost its coach Flaherty to the Navy as well, and was now lead by Dutch Bergman. The Redskins didn’t seem to notice the difference as the reigning NFL Champs picked up where they left off the year before. They extended their unbeaten streak to 17 games before losing to the Pitt-Phil amalgamation. The Giants meanwhile still hovered around 0.500. Back-to-back wins over two of the league’s weakest teams, Brooklyn and the Chicago Cardinals, boosted New York’s record to 4-3-1 and gave them a longshot opportunity to steal the Eastern Division title from Washington if they could sweep the final home-and-home series with the Redskins. The first game at the Polo Grounds was originally scheduled to be the season finale, but a conflict forced the game at Griffith Stadium to be tacked on at the end of the season.

New York entered the game in mostly good shape. Walls, who had been out since injuring his knee in a game against the Bears three weeks earlier, was tentatively scheduled to return, which was just in time as Adams broke his jaw in the Dodgers game. Second year man Frank Liebel would also be relied upon heavily. Owen was counting on a good performance from his battle tested veterans like Hein, Cuff, Leemans, Cope and Soar to lead the mostly inexperienced team against the tough Redskins. Very few of the young players had ever faced a passer the caliber of Baugh, who would end the season as the league leader in three categories: passing, punting and interceptions, to become the first “Triple Crown” winner. Baugh though, would miss the protection from his All-Pro guard Dick Farman, who had injured his knee a week earlier, and wingback Wilbur Moore.

The crowd of 51,308 was treated to another Giants-Redskins late-season thriller. Early on there did not seem to be much potential for drama. Washington controlled the ball for most of the first half but did not take the lead until 18 seconds before the intermission with a 26-yard Masterson field goal. New York’s sound defense kept Washington out of the end zone. Owen explained his strategy for Baugh, who completed 16 passes for only 154 yards, “The Giants had good luck with Baugh because, unlike other teams, we figured out it was a waste of manpower trying to rush him. He could throw too fast to be stopped. We didn’t try to stop him. Instead, we covered his receivers closely to hold all gains to short ones and to tackle those receivers so hard that they had to pay full price for every yard.”

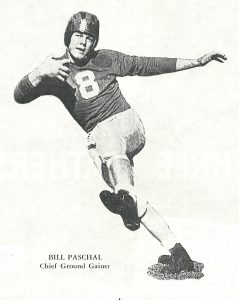

Washington seemed to solve the Giants scheme on the first drive of the third quarter. Farkas carried the load, pounding the ball eight times for 63 yards before landing on pay dirt to give the Redskins a 10-0 advantage. The Giants responded with a revived running game of their own, starting from their 28-yard line. Two Bill Paschal rushes totaled 31 yards; a Cuff reverse advanced another 21 yards to the Washington 20-yard line. Paschal carried the ball four consecutive plays before going over for the score to bring the Giants back to 10-7.

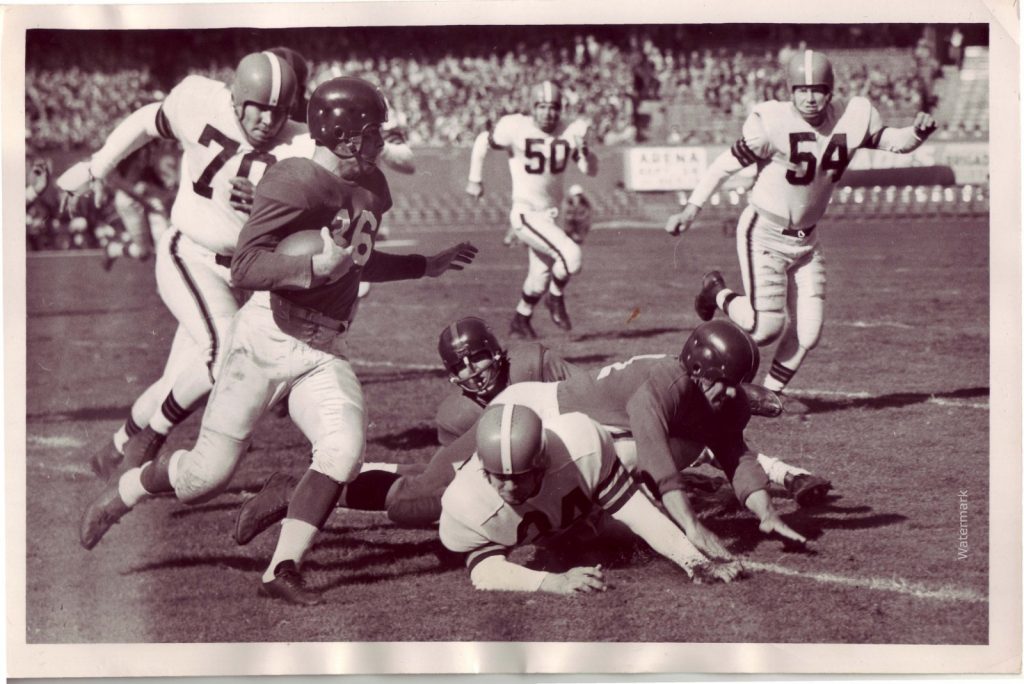

Washington Redskins at New York Giants (December 5, 1943); Al Blozis (#32), Len Younce (#60), Frank Cope (#36)

The New York defense held and the Paschal-Cuff tandem went back to work while the buzz in the Polo Grounds grandstands grew to a roar. The Giants marched from their 34-yard line to the Redskins 21 on three rushes, with only a touchdown-saving tackle from Baugh on Paschal preventing New York from taking the lead. Ultimately Baugh’s defensive effort kept Washington ahead, as the drive stalled and Wilkin blocked Cuff’s 22-yard placement.

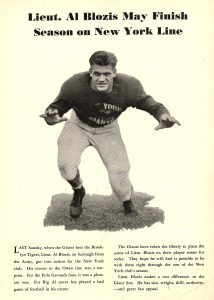

Both defenses tightened, the two teams repeatedly traded punts as the game became a struggle for field position. Tackle Al Blozis in particular was a force in New York’s clampdown on the Redskins futile advances while Masterson spearheaded the Washington resistance. Time became an ally for Washington, as even escaping with a tie would lock up the division. Just over five minutes remained when Paschal returned a punt 20 yards to the New York 44-yard line. Paschal plunged once for three yards to set up what Owen later described as the “perfect” play.

Paschal took the hand-off from Leemans after an end-around fake, charged through right tackle, paused, then outraced Baugh to the end zone. The play’s success was a result of both scheme and slick ball handling. Owen said, “Emery Nix was the left half, Dave Brown the wingback. Brown faked his end-run reverse so well he drew off the Redskins secondary. Meanwhile, Paschal roared through the quick opener hole over guard after their guard had been trapped. All Bill had to do was sprint – along the shortest distance to the touchdown, a straight line – to win the game.” Baugh explained his reaction from the safety position, “I expected a pass, particularly since Brown a fast runner and a fresh man, had just been put in there. I wasn’t fooled by the ball-handling, but was going over on pass defense assignment to pick up either the end or the wingback.”

New York was ahead for the first time 14-10 and every fan in the Polo Grounds was on their feet in a state of bedlam. Washington returned the kickoff to their 45-yard line, but the excellent starting field position went for naught as the Giants secondary defensed four Baugh aerials in a row, allowing New York to take over on downs. “Baugh was seldom dangerous on the long ones because he lofted the ball so high,” said Owen.

Karcis and Leemans took turns on line plunges and moved the chains once for a first down before kneeling down to expire the game clock. Paschal had earned the reprieve, his work for the day established a franchise record with 188 rushing yards on 24 carries, most of which came in the second half. No doubt Owen wanted to preserve him for the next game. His two touchdowns gave him 10 on the season, good for a first place tie with Green Bay’s prodigious Hutson. More good news for the Giants arrived from out of town, the Packers defeated Pitt-Phil, allowing New York to ascend to second place.

Owen stated he was “delighted” with the Giants line as they limited Washington’s ground game to 69 yards on defense while opening holes in the Redskins front for 270 yards on offense. However, the New York passing game was dreadful – seven attempts yielded a meager two completions for seven yards. The Giants won the league’s coin flip, enabling them to host the divisional playoff in the event they were able to upset Washington again. It would be the second playoff since divisional play began in 1933 and the first in the East (the Packers and Bears participated in the first playoff in 1941). Owen said he did not expect a let down from his team, “I think most of the boys realize next Sunday’s battle is merely the second half of one and the same ballgame. We’re leading at the end of the first half.”

While Masterson of the Redskins boasted his enthusiasm toward a championship rematch with the Bears, Chicago co-coach Anderson offered his observation, “I saw the Giants play Washington in New York Sunday. It was such a viciously fought game… officials told me afterward that it was one of the toughest games they worked all year.” The Giants appeared in relatively good health for the week of practice, while the Redskins training staff was busy tending to several key players, including Farkas, Wilkin and Masterson who nursed an assortment of injuries incurred the previous week. Farman and Moore would also miss their second consecutive games.

Griffith Stadium was filled to the brim with 35,504 rabid fans anticipating a blowout. They got one, but it was the Redskins who were on the receiving end. The New York Times stated “the once-haughty champions of the National Football League were bounced all over Griffith Stadium” and “were thoroughly outplayed in every department, including that of effective passing.” There was little mystery as the statistics told the complete story. After Washington took a 7-0 lead in the second quarter on a Baugh touchdown pass, the tide turned quickly. Frank Cope blocked a Baugh punt that was recovered by Steve Pritko for the tying touchdown. Emery Nix completed a 75-yard touchdown pass to Frank Liebel soon after for a 14-7 halftime lead. All told, New York intercepted five of Baugh’s 28 attempts over the course of the game, and they capitalized often in the 31-7 romp. Paschal churned out 92 yards rushing for the Giants as they dealt Washington their third consecutive loss, the first time they had endured such a streak since 1937.

First Playoff in the East

Practices at the Polo Grounds included lineup shuffling, as they hoped to extend the Redskins doldrums one more week in the playoff. Liebel was out for the playoff, having suffered a broken nose in the season finale. Guard Charley Avedisian had his arm in a sling after suffering a shoulder separation. Adams, who had missed the first two Washington games was being fit with a special face guard for his still healing broken jaw. The Redskins hoped to change their fortunes by altering their normal routine. They arrived two days earlier than normal for a road game, and sequestered themselves in Westchester County rather than Manhattan. Despite Farman and Moore being out of the lineup again, Bergman said his team was in overall better shape.

Commissioner Elmer Layden decreed the game required a victor. Should the score be tied after 60 minutes, there would be a 15-minute sudden death overtime period following a three-minute period of rest. If the game remained tied after the initial overtime, the process would repeat itself until a team scored.

The advance planning for such a contingency proved completely unnecessary. Much to the dismay of most of the 42,800 fans in attendance, the Redskins returned the previous week’s favor by whipping the Giants in front of their own fans, 28-0.

Owen believed that “as Baugh goes, so go the Redskins.” That proved to be true once again. In the first game, Baugh played well but not spectacularly. In the second game he was dreadful. In the playoff he was magnificent, completing 16-of-21 for 199 yards, one touchdown and two interceptions on offense. He also intercepted one he returned 38 yards to set up a score, and added a 65-yard punt for good measure. His sharp passing forged three scoring drives that were capped off by short Farkas touchdown plunges. Overall, the Washington defense held New York to eight first downs and 112 total yards. Leemans was 4-of-20 passing with three interceptions while the Giants three-headed rushing attack was held in check.

Despite the disappointment of the one-sided defeat, the Giants were lauded for coming from seemingly nowhere and extending their season while pushing the defending champions to the brink. The conjecture was they were spent by the chase and had little left, while Washington shook off their malaise and finally performed to their full capability. The Redskins won the Eastern Division for the third time in four years, but failed in their attempt to become the first team to win consecutive championship games, as the Bears – who were on a week’s rest – defeated them handily in Wrigley Field 41-21.

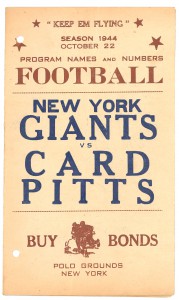

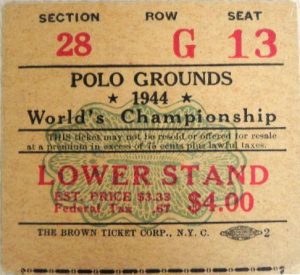

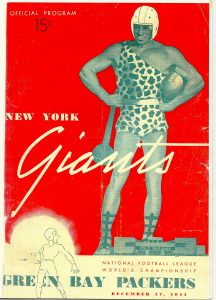

The 1944 season saw more change in the NFL. The Pitt-Phil combine ceased and the Card-Pitt was formed, the Rams resumed operations and the Brooklyn Dodgers were now known as the Tigers. More significantly though, was the catching on of the T-Formation. The Bears had led the league in scoring three consecutive seasons and convincingly won three of the last four championships running the system that was now spreading through the colleges. Washington was now on the bandwagon, although their chief operator was reluctant at first, “I hated the T when we went to it on 1944,”said Baugh years later, “but my body loved it. I probably could have lasted a year or two more as a single wing tailback, my body was so beat up, but the T gave me nine more seasons.”

The Giants and Redskins were involved in another back-to-back season-closing pressure cooker that set the fate for three teams in the East. New York won out and lost to Green Bay in the NFL Championship Game at the Polo Grounds 14-7. That game holds the distinction of being the last time two Wing-style teams squared off in a title game (the Giants base set was the A-Formation and the Packers the Notre Dame Box.)

The Giants and Redskins were involved in another back-to-back season-closing pressure cooker that set the fate for three teams in the East. New York won out and lost to Green Bay in the NFL Championship Game at the Polo Grounds 14-7. That game holds the distinction of being the last time two Wing-style teams squared off in a title game (the Giants base set was the A-Formation and the Packers the Notre Dame Box.)

(See “Missing Rings: The 1944 New York Football Giants” for more detail.)

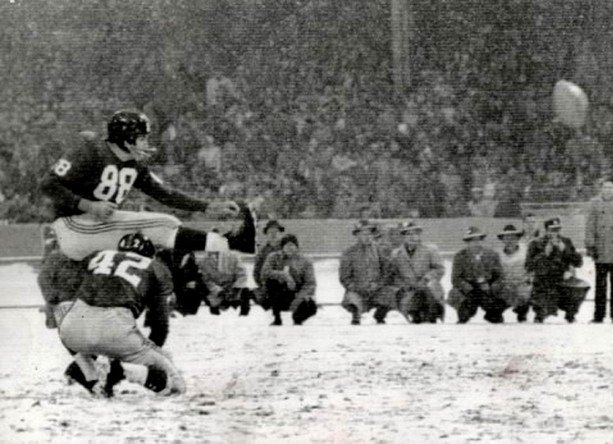

Washington represented the East in the championship game for the sixth time in 10 seasons in 1945 with an 8-2 record as Baugh became comfortable operating from the T-Formation. They swept the Giants, who declined significantly to a 3-6-1 record. The Redskins lost the Championship Game at frozen Cleveland Municipal Stadium against the Rams where a safety proved the difference in a 15-14 game, forging a significant rule change. In the first quarter, the Redskins had the ball on their own five-yard line. Baugh dropped back to pass from his own end zone, but the attempt struck the goal post and the ball bounced dead in the end zone. The rules at the time declared this to be a safety and gave the Rams a 2-0 lead. The following off season the rule was changed so any pass striking the goal post was called incomplete.

Ignominious End

The Giants revamped their roster for 1946. Hein retired for good after a record 15 seasons, tied with Jack Blood who played with Green Bay and Pittsburgh from 1925-39. Tailback Arnie Herber also retired, so New York signed Filchock away from Washington to the very first multi-year contract in New York’s history – three years for $35,000. Filchock had made a smooth transition from the Double Wing to the T-Formation in 1944, Owen hoped he could do the same learning the nuances of the unique A-Formation.

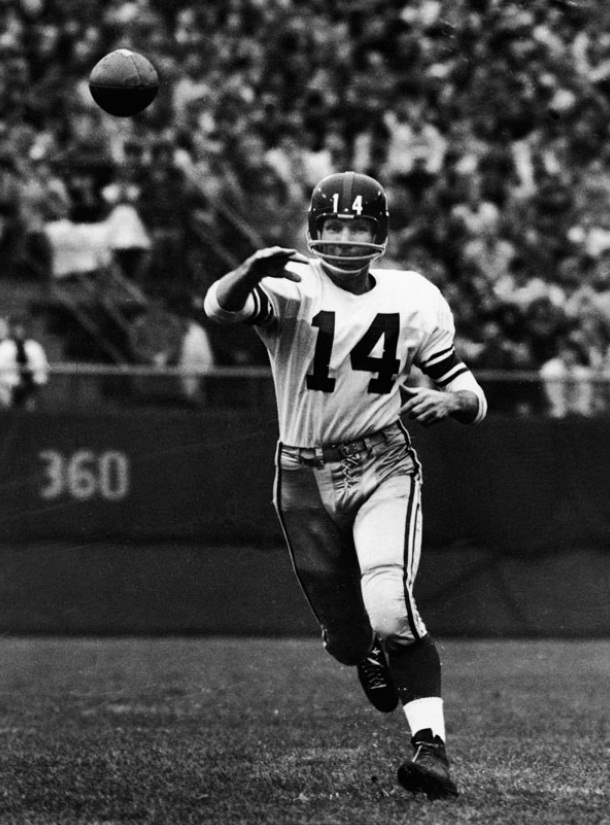

Filchock did, and he led the Giants in both passing (1,262 yards with 12 touchdowns) and rushing (371 yards and two touchdowns). New York won the East with a 7-3-1 record while Washington slumped to 5-5-1. Washington won the October match-up at Griffith Stadium 24-14 and had a chance to force a playoff with the Giants with a win in the season finale at the Polo Grounds.

New York Giants at Washington Redskins (October 13, 1946)

The most notable points from New York’s 31-0 whipping of their rivals was the crowd of 60,337, the Polo Grounds largest since the 1939 Redskins game; Ken Strong tying Ward Cuff as the Giants career leading scorer; and Filchock outplaying former teammate Baugh. Although Baugh accrued more yards through the air (240-142), Filchock was more efficient, threw two touchdown passes and was on the receiving end of one of Baugh’s three interceptions. The Giants won the Eastern Division for the eighth time in its 14 years.

Unfortunately for Filchock, his legacy is usually focused on an attempted fix of the Championship Game with the Bears. Fluctuation in the point spread triggered an investigation; undercover police observed Giants practices and wiretaps were installed on the business phone of a known gambler, Alvin J. Paris. No New York players were ever heard on the phone, but Paris mentioned Filchock and Merle Hapes by name to his associates.

Mara and NFL Commissioner Bert Bell were summoned to New York City Mayor William O’Dwyer’s office Saturday afternoon to meet with Police Commissioner Arthur Wallander. The two players were interrogated there at 2:00 AM. Filchock denied any involvement, while Hapes admitted to being offered $2,500, the profits of a $1,000 bet that Chicago would cover the 10-point spread and an offseason job that would earn him $15,000.

Both players were cleared by the police and Paris was arrested and held on $25,000 bail (he ultimately served one year in prison after testifying against other members of his syndicate). Bell publically stated the morning of the game that the NFL would continue with its own investigation into the offers. Hapes was barred from playing in the game for failure to report the bribe offer being made.

Fans heard of the late night intrigue over the radio that morning, and Filchock was robustly booed and hackled when he stepped on the Polo Grounds field. According to all reports he played valiantly in defeat, even if his statistics may not have born this out. His six interceptions were detrimental in the Giants 24-14 loss, rendering the 10-point spread a push. Angry Chicago players took umbrage in dealing extra punishment to Filchock whenever the opportunity allowed, but he played just over 50 minutes of the contest.

Flichock ultimately acknowledged he did receive a bribe offer from Paris. Both he and Hapes received lifetime bans from the NFL for being “guilty of actions detrimental to the welfare of the National Football League and of professional football.” Hapes retired from football altogether and Filchock, after being rejected by the AAFC, played seven more seasons in the CFL.

New York and Washington’s shared reign in the Eastern Division came to a close in 1947. Earl “Greasy” Neal’s Philadelphia team, whose version of the T-Formation was powered by the dynamic Steve Van Buren, won out the final three seasons of the decade, capturing the NFL title the last two. The Giants began an uneasy transition to the T-Formation in 1949, but never fully committed to it until Owen’s departure after the 1953 season as he routinely reverted to his A-Formation.

A new rivalry for the Giants was born in the new decade. The merger of the NFL and AAFC introduced New York to the Cleveland Browns, whose innovative coach Paul Brown explored the Halas T-Formation further and developed it into a pass-first scheme. The Eastern Division was renamed the American Conference for three seasons, then the Eastern Conference through 1966. Over the 17-season span from 1950 through 1966 Cleveland and New York dominated their half of the league, as the Giants and Redskins had previously. New York and Washington would renew their battles for division supremacy in the post AFL-NFL merger in the mid 1980’s.

Overall Regular-Season Record: Giants led series 13-8-1

Overall Playoff Series Record: Washington led series 1-0 (1943 Divisional Playoff)

1936

10/4 Giants 7 at Boston 0

12/6 Giants 0 vs Boston 14

1937

9/16 Giants 3 at Washington 13

12/5 Giants 14 vs Washington 49

1938

10/9 Giants 10 at Washington 7

12/4 Giants 36 vs Washington 0

1939

10/1 Giants 0 at Washington 0

12/4 Giants 9 vs Washington 7

1940

9/22 Giants 7 at Washington 21

11/24 Giants 21 vs Washington 7

1941

9/28 Giants 17 at Washington 10

11/23 Giants 20 vs Washington 13

1942

9/28 Giants 14 at Washington 7

11/15 Giants 7 vs Washington 14

1943

12/5 Giants 14 vs Washington 10

12/12 Giants 31 at Washington 7

*12/19 Giants 0 vs Washington 28

1944

12/5 Giants 14 vs Washington 10

12/12 Giants 31 at Washington 7

1945

10/28 Giants 14 vs Washington 24

12/12 Giants 0 at Washington 17

1946

10/13 Giants 14 at Washington 24

12/12 Giants 31 vs Washington 0

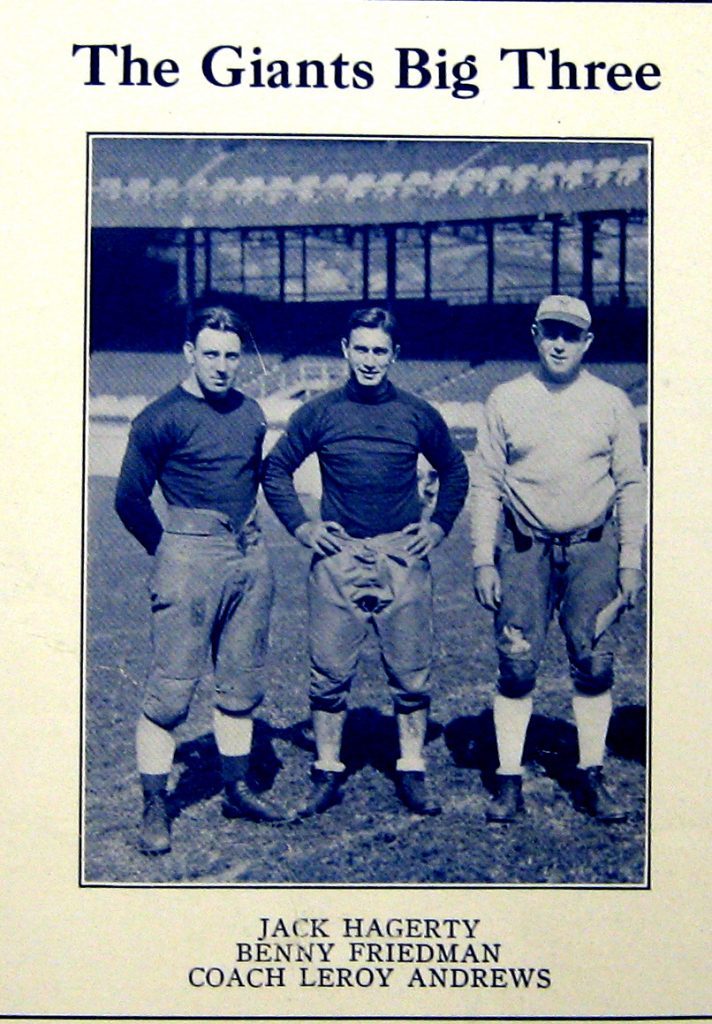

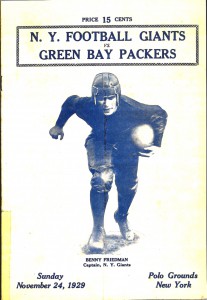

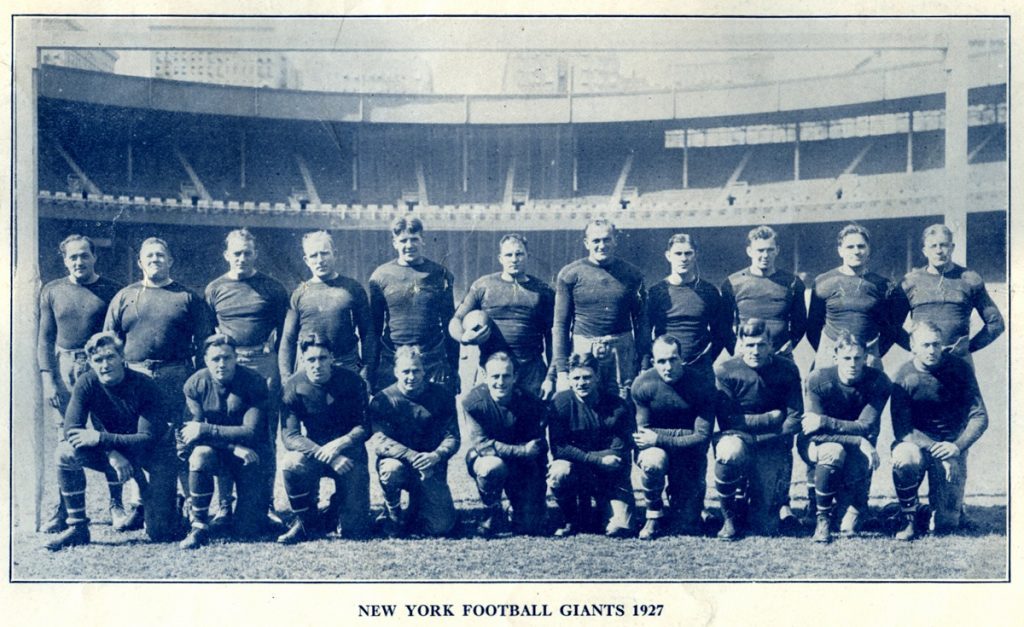

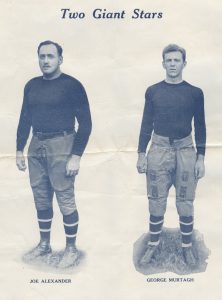

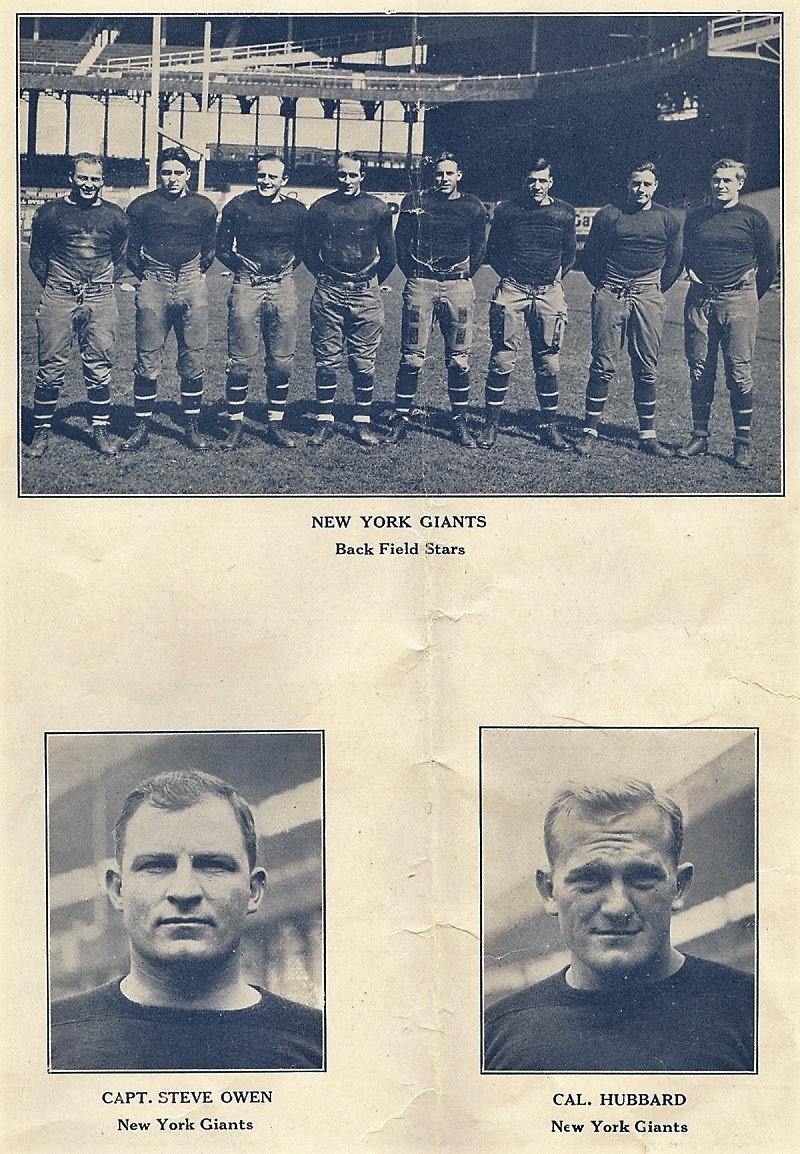

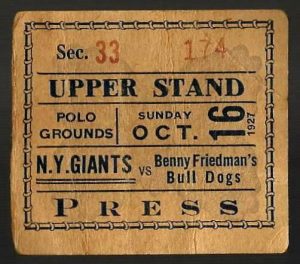

In the re-match against Cleveland, Friedman arrived several days ahead of his Bulldog teammates and was lavished with several honors, not the least of which was a gala event in his honor at the Hotel Majestic. Despite this being just his fourth professional game, he was easily one of the NFL’s marquis attractions among the likes of newsreel sensations Red Grange and Ernie Nevers. The Giants even printed the tickets for the game to read: “N.Y. Giants vs Benny Friedman’s Bulldogs”.

In the re-match against Cleveland, Friedman arrived several days ahead of his Bulldog teammates and was lavished with several honors, not the least of which was a gala event in his honor at the Hotel Majestic. Despite this being just his fourth professional game, he was easily one of the NFL’s marquis attractions among the likes of newsreel sensations Red Grange and Ernie Nevers. The Giants even printed the tickets for the game to read: “N.Y. Giants vs Benny Friedman’s Bulldogs”.

Howell had traveled to Mississippi that off-season and promised Conerly if he came back he would be better protected. To make the existence of his reluctant quarterback more comfortable, the A-Formation was discarded, the T-Formation fully installed, terminology simplified, and a system of automatics that enabled Conerly to change the play at the line was developed.

Howell had traveled to Mississippi that off-season and promised Conerly if he came back he would be better protected. To make the existence of his reluctant quarterback more comfortable, the A-Formation was discarded, the T-Formation fully installed, terminology simplified, and a system of automatics that enabled Conerly to change the play at the line was developed.

The Giants opened the season at Cleveland in what would be a tense defensive battle. Brown rushed for 89 yards on 21 carries, but neither team accumulated 200 total yards of offense. Cleveland won on a Groza kick at 0:23, 6-3. The Giants rebounded to win seven of their next eight games, fueled in part by another Landry defensive innovation: a linebacker “red dog” in which at the snap of the ball, Huff or one of the outside linebackers would immediately attack the backfield.

The Giants opened the season at Cleveland in what would be a tense defensive battle. Brown rushed for 89 yards on 21 carries, but neither team accumulated 200 total yards of offense. Cleveland won on a Groza kick at 0:23, 6-3. The Giants rebounded to win seven of their next eight games, fueled in part by another Landry defensive innovation: a linebacker “red dog” in which at the snap of the ball, Huff or one of the outside linebackers would immediately attack the backfield.

Weinmeister was a rare physical specimen. At 6’4” and 240 pounds, he had the strength to consistently win skirmishes in the trenches, but it was his fluid athletic ability, speed, and the desire to dominate that set him apart. He regularly terrorized quarterbacks in the pocket and tackled backs and receivers downfield. When Weinmeister joined the Giants, he told Owen the way to defeat Cleveland was “to knock them on their butts.” Weinmeister and fellow tackle Al DeRogatis were charged with crashing the pocket on pass plays, and funneling Motley to linebacker John Cannady on rushes.

Weinmeister was a rare physical specimen. At 6’4” and 240 pounds, he had the strength to consistently win skirmishes in the trenches, but it was his fluid athletic ability, speed, and the desire to dominate that set him apart. He regularly terrorized quarterbacks in the pocket and tackled backs and receivers downfield. When Weinmeister joined the Giants, he told Owen the way to defeat Cleveland was “to knock them on their butts.” Weinmeister and fellow tackle Al DeRogatis were charged with crashing the pocket on pass plays, and funneling Motley to linebacker John Cannady on rushes.