by Larry Schmitt | Nov 17, 2016 | Articles, New York Giants History

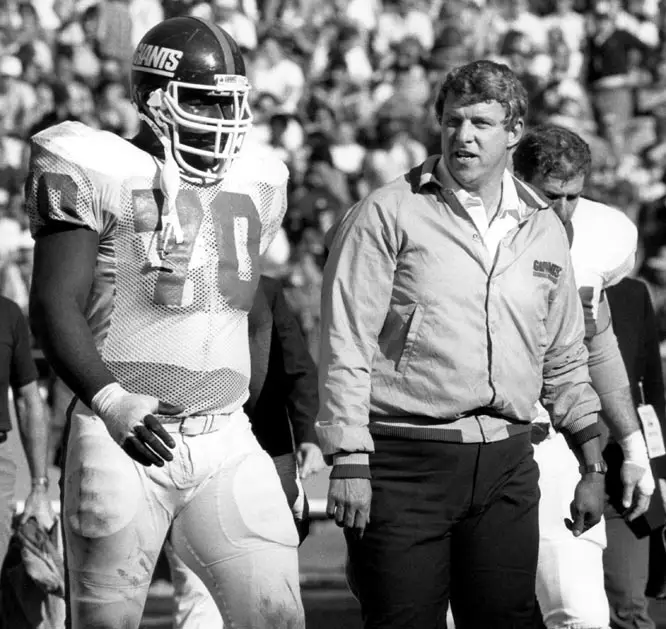

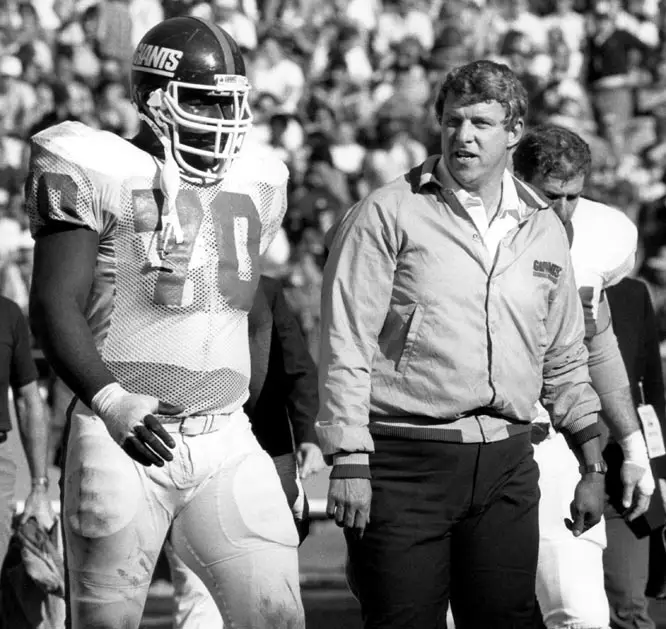

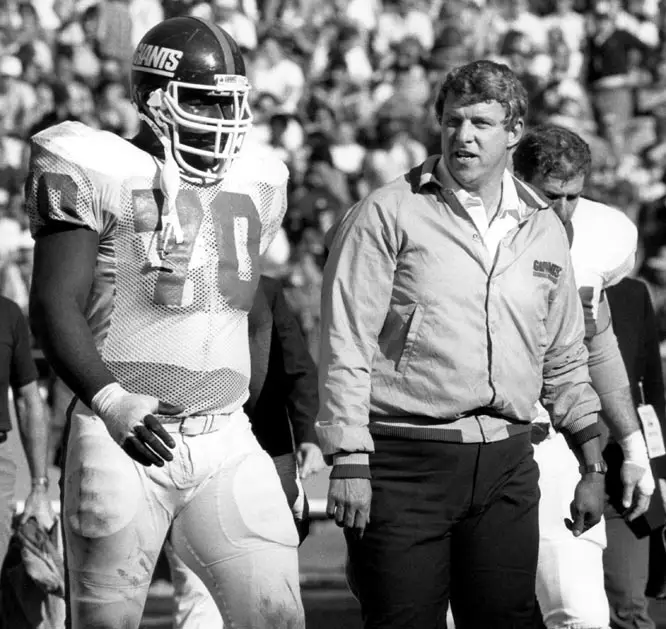

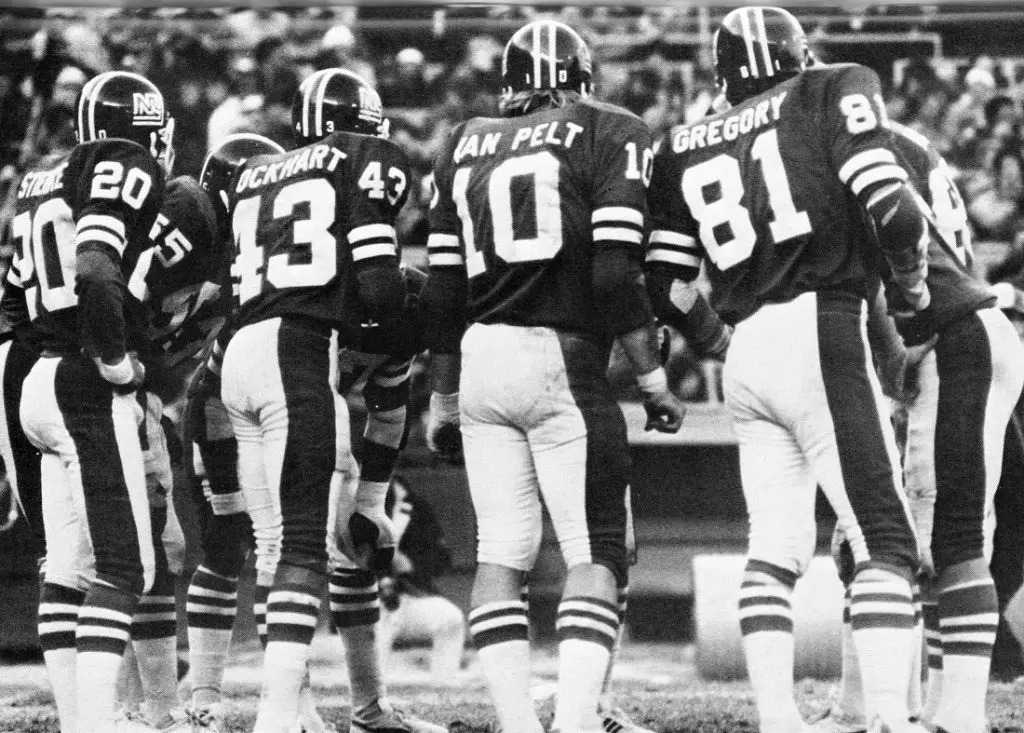

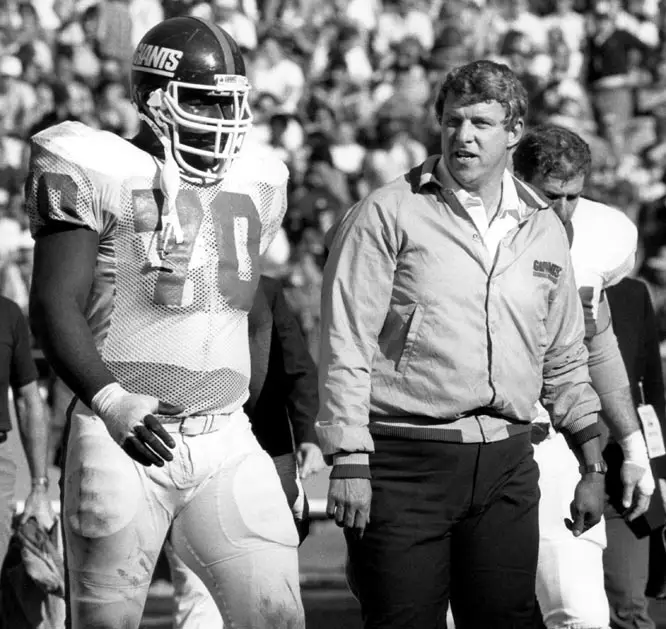

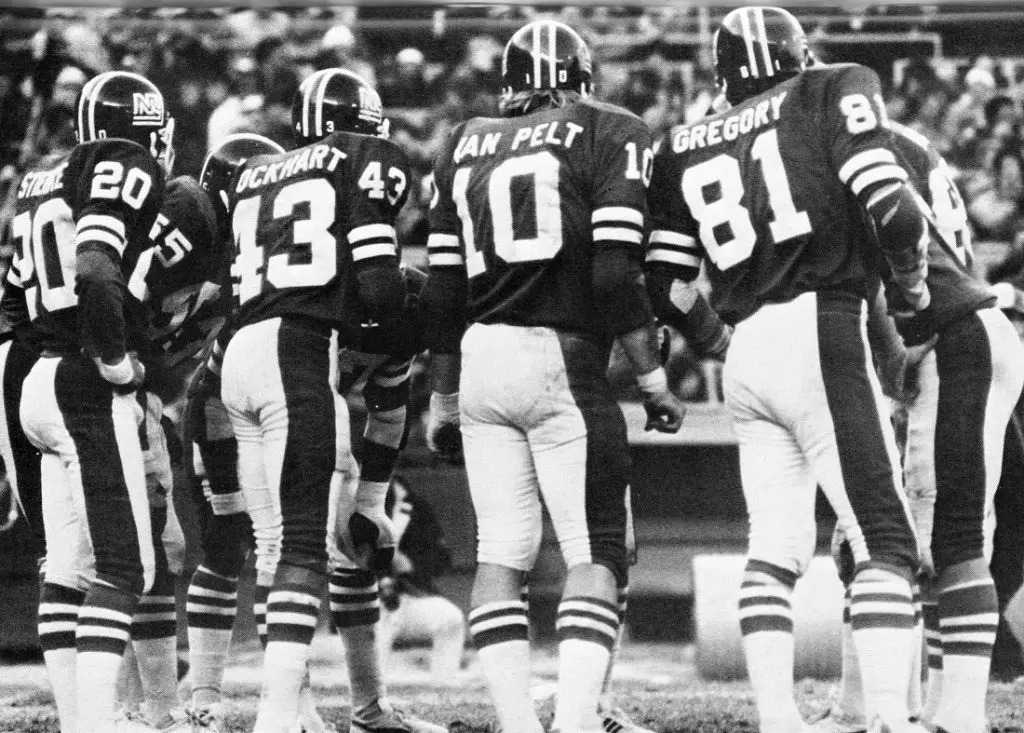

By Larry Schmitt, with contributions from Matt Michelman The day after the close of the 1978 season, and 29 days after The Fumble, December 18, 1978, John McVay was released as head coach of the New York Giants and Andy Robustelli resigned as director of football...

by Larry Schmitt | Aug 7, 2016 | Articles, New York Giants History

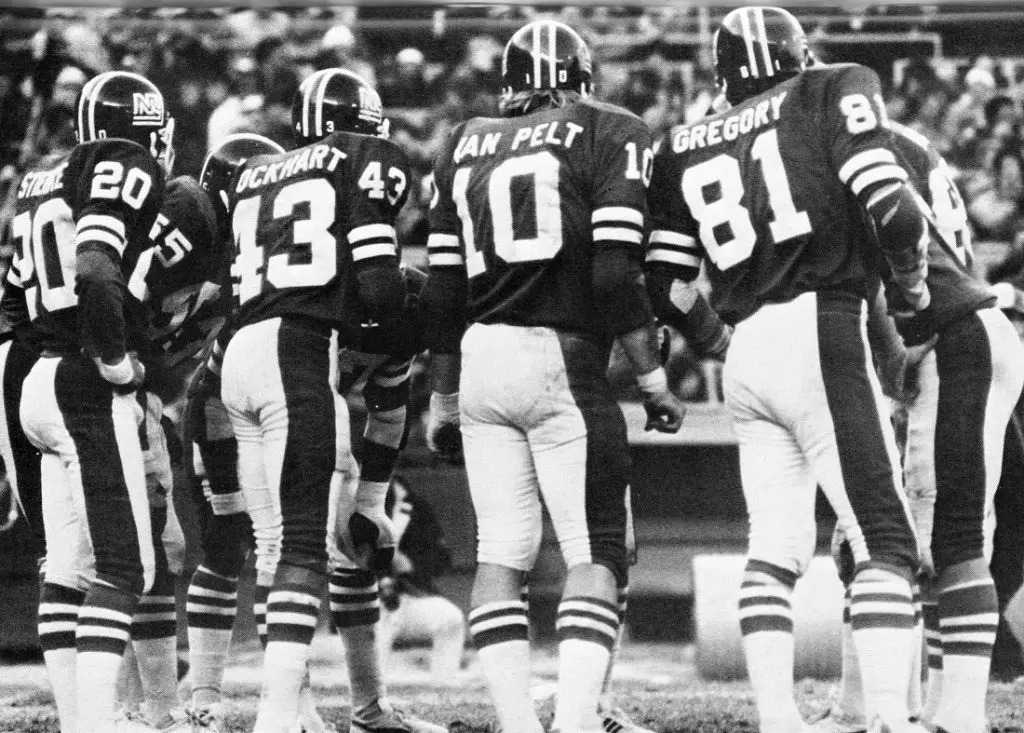

The first chapter of the New York Football Giants history closed on December 29, 1963. Up until that time, one of the cornerstone franchises of the NFL, the Giants prospered on the field while they regularly struggled financially to stay afloat. The franchise nearly...