by Larry Schmitt | May 30, 2015 | Articles, New York Giants History

By Larry Schmitt with contributions from Daniel Franck and Dr. Bruce Gilbert The 1956 season was a watershed moment for football in New York. Filled with potent portent, the campaign proved to be the penultimate piece of the puzzle for the ultimate explosion of pro...

by Larry Schmitt | Jan 22, 2014 | Articles, New York Giants History

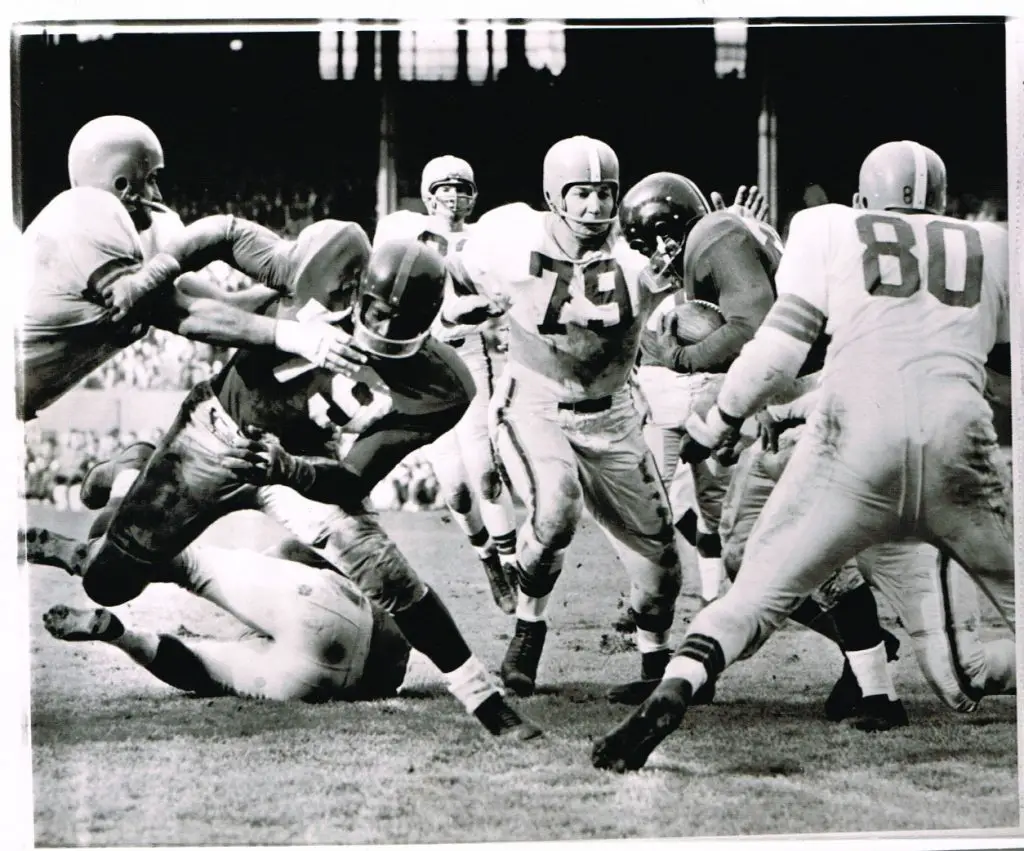

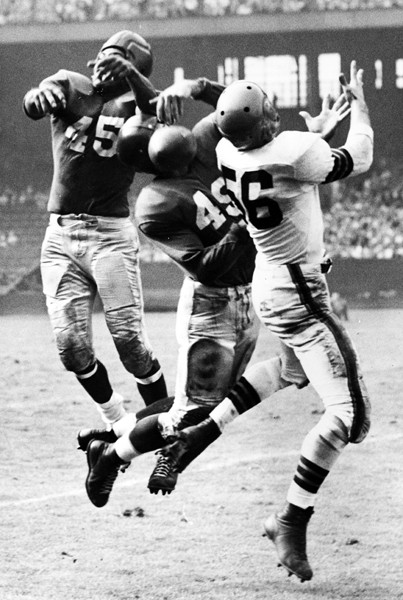

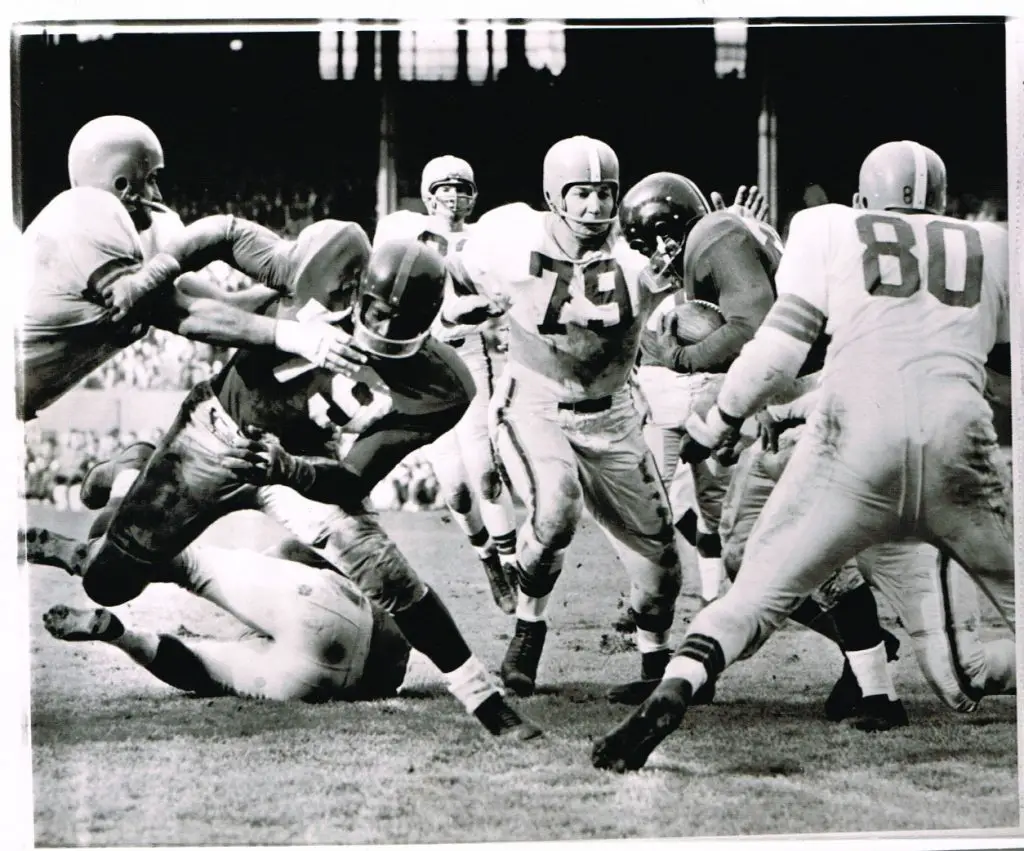

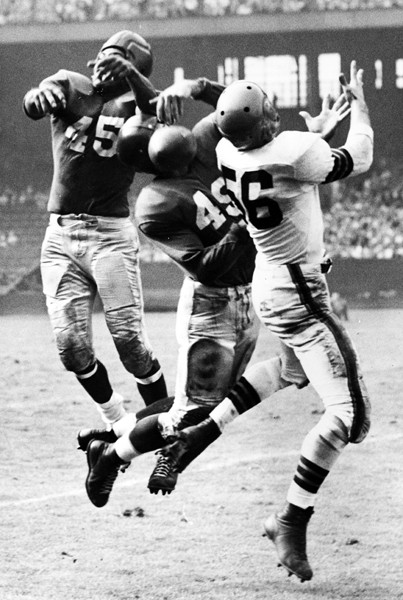

New York Giants – Cleveland Browns 1950-1959 (Part II) (Part I) Innovation via Delegation The New York Giants first sought Army Black Knight Head Coach Earl “Red” Blaik as the replacement for Owen. After he declined the offer, assistant coach and former end Jim...

by Larry Schmitt | Jan 20, 2014 | Articles, New York Giants History

New York Giants – Cleveland Browns 1950-1959 (Part I) When most people think of a fierce rivalry, the first image to arise is often a series of intense, physical contests – two teams meeting on the field, imposing wills, doling out punishment, one trying...

by Eric Kennedy | Oct 31, 2013 | News and Notes

Giants.com Q&A With Wide Receivers Coach Kevin M. Gilbride: The video of a recent Giants.com Q&A session with Wide Receivers Coach Kevin M. Gilbride is available at Giants.com. Giants.com Q&A With RB Andre Brown: The video of a recent Giants.com Q&A...