The 1934 New York Giants

The New York Giants surprising victory over the Chicago Bears in the 1934 NFL Championship Game is noted in professional football’s lore as “The Sneakers Game.” Most fans today are vaguely aware that the underdog Giants switched to sneakers at halftime, gained better traction on a frozen field and walked off victors after a fourth quarter romp.

What many people do not remember is how dominant the 1934 Bears were and how shocking an upset that game was. The 1934 campaign also served as portent for two future Giants teams: the 1990 and 2007 Super Bowl Champions.

The Streak Starts

The year before the championship run, the Giants dealt the Bears a 3-0 loss in November 1933 at the Polo Grounds. Ken Strong’s placement kick just before halftime proved to be the difference in a slugfest between two of the league’s strongest lines. The Giants and Bears went on to win their respective divisions in the newly-re-aligned league and met in the NFL’s first official championship game. Chicago won 23-21 in a game that featured six lead changes and ended with a game saving tackle by Red Grange on the final play.

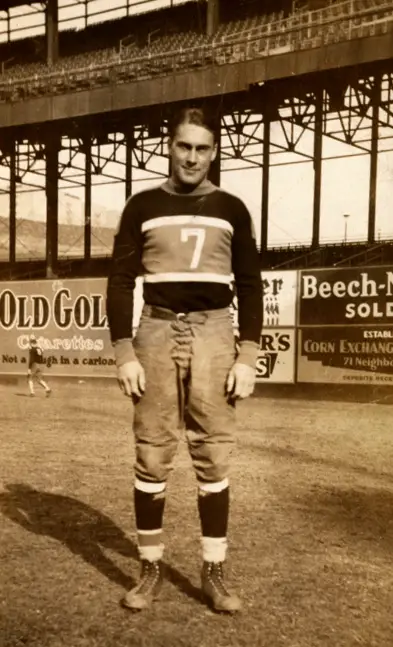

New York Giants Center/Linebacker Mel Hein in 1933 – Photo Courtesy of Rev. Mike Moran

There were two major factors responsible for transforming George Halas’ 1934 Chicago squad from very good to almost invincible. These were the addition of rookie HB Beattie Feathers and the concept of putting a man-in-motion laterally to the line of scrimmage prior to the snap of the ball.

Feathers proved to be the ultimate backfield compliment for the bruising FB Bronko Nagurski. Feathers had speed to get around the ends, and once Nagurski took out the first level of defense, Feathers would kick into the next gear. Feathers was the NFL’s first 1,000-yard rusher that year, gaining 1,004 on only 101 carries, an amazing 9.9 yard-per-carry and a league leading eight TDs. {Feathers also happened to be a bit of an eccentric, he disliked socks and played barefoot in his cleats.} Nagurski brutalized defensive fronts with plunges between the tackles, usually unblocked. Giants Head Coach Steve Owen noted with admiration, “He’s the only man I ever saw who ran his own interference.”

Halas and assistant coach Ralph Jones boasted the NFL’s deepest playbook with over 150 plays. Among the usual wing variations was the T-formation. The T had been around since the early 1920’s, but three things set the Halas/Jones version apart from the standard versions in use at the time: wider splits by the offensive line, the quarterback taking the snap from under center, and the man-in-motion. Defenses were confounded and slow to adapt. Halas recalled years later, “Our modern T-Formation with man-in-motion was the most successful strategy in football. Even so, very few coaches and players yet saw the lessons. They still continued with the wings and boxes. That was fine with me.”

Chicago had more going for them than concepts, they had size. The Bears front line was formidable, outweighing defenses on average by 20 pounds per man. Behemoths George Musso, Link Lyman, and Carl Brumbaugh tromped the opposition. Chicago went 13-0 and outscored their victims by a whopping 286-86 margin, while playing just five games on their home field.

Meanwhile, the 1934 New York Giants started off slowly, dropping their first two games while scoring a meager six points in total. A five-game winning streak saw New York improve incrementally and build confidence. Their first encounter with the Bears came at Wrigley Field, and the Chicago fans watched a 27-7 whipping of the visitors.

The Giants recovered with a hard fought 17-3 win at home versus Green Bay, where TB Harry Newman rushed for 114 yards on an NFL record 39 carries. After the game, Newman quipped that none of the Giants other backs would take the ball from him because Green Bay tackle Cal Hubbard was knocking the stuffing out of them. With their confidence restored, the Giants prepared for a rematch with the Chicago juggernaut.

The Giants enjoyed the support of the largest crowd at the Polo Grounds since the 1930 game versus Knute Rockne’s Notre Dame All Stars. Giants had won 12 straight at home, and lead 7-0 after Ken Strong’s 4-yard run on the first play of 2nd quarter. The Giants added to their lead with a safety after Chicago’s return man fielded the ball on the 1 yard-line, ran backward and was tackled in the end zone. Chicago, however, assumed control of the game with their powerful lines.

The Giants lost their starting TB and leading passer. Newman was injured on a tackle by Bill Hewitt and Musso. Hewitt’s knee hit Newman in the back and he lied motionless on the field for several minutes. X-Rays later revealed two fractured vertebrae, ending his season.

Despite Chicago’s physical dominance, the Giants nursed their 9-0 advantage into the fourth quarter. Nagurski and Feathers churned out yardage on a long touchdown drive to cut the lead to 9-7. The Giants were in position to run out the clock when an untimely error foiled their bid for the upset win. Carl Brumbaugh recovered a Max Krause fumble on the Giants 33-yard line with less than two minutes to play. “Automatic” Jack Manders sealed the Giants fate when he connected on a 24-yard field goal with seconds left on the clock giving the Bears a 10-9 win.

Chicago swept their remaining three games to complete the first undefeated and untied regular season in NFL history (13-0), while the Giants finished 2-1 in their last three games with rookie Ed Danowski ably filling in for Newman. The Giants finished the regular season 8-5. Their season ending loss at Philadelphia was costly. All Pro end Red Badgro fractured his knee cap and would be unavailable for the championship match. The Bears also lost HB Feathers to a shoulder injury.

Mr. Everything

The player the Giants counted on most to shoulder the load with the depleted backfield was FB/LB/K Ken Strong, who incidentally came into the championship game with an injured ankle of his own. Strong was a multi-talented local hero, and graduate of NYU.

The Giants thought very highly of Strong, who boasted many of what would be considered today as “impressive measurables.” He was a powerful runner who ran the 100 in less than 10 seconds and was an effective lead blocker, could kick 45-yard field goals and punt 70 yards. It’s no wonder famed sports writer Grantland Rice selected Strong as an All Time HB alongside the legendary Jim Thorpe.

In 1929, Giants Owner Tim Mara instructed head coach LeRoy Andrews to offer Strong $4,000 to play for the Giants. The duplicitous Andrews offered Strong $3,000 – with the intention of pocketing the difference. Strong signed with the rival Staten Island Stapletons instead. (This unscrupulous practice of skimming player contracts cost Andrews his job during the 1930 season.)

New York Giants Ken Strong Kicking and Bo Molenda Holding in 1934 – Photo Courtesy of Rev. Mike Moran

Strong also had a promising baseball career on the horizon. The Detroit Tigers thought so highly of him that they traded five players and $40,000 to the New York Yankees for his rights. Unfortunately, while playing in the minors, Strong broke his wrist running into an outfield wall. His surgery was botched when the physician removed the wrong bone from his wrist, ending his baseball career. The Stapletons’ franchise folded after the 1932 season and the Giants were pleased to finally acquire the player they had coveted in time for the 1933 season. “It was a big boost when Strong joined the club”, Giants center Mel Hein recalled, “I had read about him in Grantland Rice’s stories and, frankly, I was a little doubtful when he was compared to Ernie Nevers and Bronko Nagurski. But when I saw him in action I became a believer. He was that good.” Strong’s first season in a Giants uniform was impressive. He led the NFL in scoring as the Giants won the NFL Eastern Division and was named to the All Pro team. He went on to score a touchdown and three extra points for the Giants in their 23-21 loss at Chicago in the NFL’s first championship game.

NFL Championship Game Redux

Noting the state of his team with substitute players at key positions, as well as the prospect of facing an awesome Bears team that had physically battered the Giants twice during the regular campaign, Owen somewhat optimistically said, “I know it doesn’t look so good, but we’ll give ‘em a battle.”

The Giants had high hopes of a record turnout on the heels of the large crowd that had attended the regular season matchup. Six thousand temporary field level seats were installed after box seats had sold out in advance. The Maras had their fingers crossed for a walk-up turnout to fill in the upper deck and bleachers. A nor’easter the night before kept most last-minute ticket buyers at home, but the turnstile count of 40,120 was still quite good for that era.

Jack Mara called Owen early that morning, “It’s bad, you can’t even walk without slipping. I don’t know what we’re going to be able to do.” Upon inspecting the field himself, Owen half-jokingly asked Danowski, “Think you can pass downfield to someone sliding on his belly?” Danowski replied, “With Musso on my neck and me sliding too?”

Once the frozen tarp was pried form the field, the game began with the Giants surprisingly moving the ball down the field. The promising drive ended with Danowski throwing an interception, but the New York defense held its ground. Bo Molenda blocked the Chicago punt and Strong put the first points on the board with a field goal. Chicago reestablished their physical dominance and controlled the remainder of the first half.

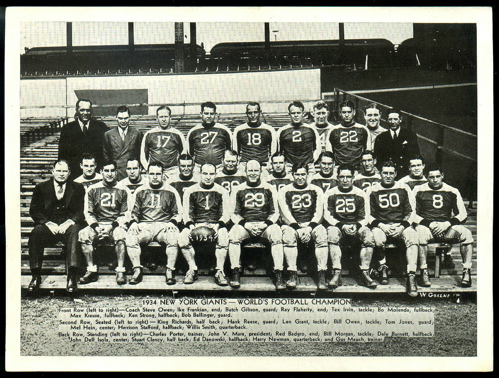

1934 New York Giants

If the Giants left the field feeling dejected, as some of the freezing fans expressed their disappointment with boos, the Bears walked off frustrated. Although they lead 10-3, the damage could have been far worse. Nagurski had two touchdowns called back on penalties in the second quarter that were both followed by missed field goals from inside 30 yards – the first Manders misses from that range all season. Aside from Bill Morgan, who Owen would cite for having “played the finest game at tackle I’ve ever seen,” the Giants had been beaten on almost every block on offense. The results on defense were not much better, as Hein said, “Nagurski was three-yarding us to death.”

Few, if any of the Giants, players were aware that help was already on the way. On the advice of End Ray Flaherty, Owen had dispatched part-time equipment man/Manhattan College tailor Abe Cohen on a quest for basketball sneakers to give the Giants better traction on the slick Polo Grounds playing surface. Flaherty had recalled that while playing at Gonzaga his team had switched footwear with great success on a frozen field at the University of Montana.

Cohen arrived in the Giants locker room just before the start of the second half with nine pairs of sneakers, all he could manage to carry. Tackle Bill Owen was the first to try a pair out, and reported to brother Steve that the rubber soled sneakers were an improvement over the plastic-bottomed cleats. Halas was not impressed as he watched the Giants change footwear on the sidelines, and was overheard commanding his players to step on the Giants toes.

The early returns were not immediately apparent however. Strong lost the toe nail from his right big toe when it split in two on the kickoff. Danowski had started the third quarter with his cleats, but after slipping on two rushing attempts he switched to the sneakers. The one Giant able to play well with the cleats was their best player, Hein. Nevertheless, despite the change in footwear, the Bears were able to add a Manders’ field goal during the third quarter and extend their lead. The 13-3 score felt like an impossible deficit to overcome to Tim Mara, who did not foresee the turn of events that were about to unfold, “Everyone was thinking of going home, and to tell you the truth, I was seriously thinking of joining them.”

The tide slowly began to turn the Giants way just before the end of the quarter. Danowski, now with good footing, found a rhythm and completed successive passes to receivers who were able to get separation from slipping defenders. An errant pass was intercepted near the Chicago goal line, but the Giants defense was stout, forcing a punt that Strong returned 25 yards to keep the Giants momentum surging. Danowski completed three short passes, two to Flaherty, one to Strong, and rushed on a keeper, then capped the drive with a 28-yard scoring pass to Ike Frankian, cutting the Bears lead to 13-10.

Danowski intercepted a pass on defense, enabling Strong to exhibit his athletic talents in the game’s pivotal play. As he took the handoff from Danowski toward left tackle, Strong headed upfield, cut to the sideline, reversed field {a move that would’ve been impossible in the cleats} and raced into the end zone for a 17-13 advantage. That 42-yard rushing touchdown remained a Giants post season record until Joe Morris scored from 45 yards in 1986 against San Francisco. Halas exhorted his team to rise to the challenge and reestablish their authority, but one player feebly replied, “Step on their toes? I can’t even get close enough to those guys to tackle them!”

The Bears did finally manage a drive that crossed into New York territory with a heavy dose of Nagurski rushes. On a fourth-and-two, Morgan fought off a block and dropped Nagurski short of a first down. Strong then closed another successful New York drive with an 11-yard sweep around right tackle. Officials paused the game to give the police time to clear delirious fans from the field. When play resumed, Strong was denied his PAT attempt when holder Bo Molenda mishandled the snap and had his drop kick attempt blocked. Following another Giants defensive stand, Danowski finished off the day’s scoring with an 8-yard touchdown run. The 27 point outburst by the Giants remains an NFL fourth quarter post season record to this day.

A secondary hero who remained somewhat in obscurity might have been Giants trainer Gus Mauch. Upon noticing the Giants water buckets had frozen early in the third quarter, he shared whiskey with players in paper cups filled from his flask, ostensibly to keep them warm. After the Giants had taken the lead 17-13 and his flask had emptied, Mauch walked over to the stands for a resupply from patrons. Members of the sideline staff urged Mauch not to give the players any more liquor in fear of them becoming inebriated.

Naugurski attributed the difference late in the game to the footwear provided by Cohen, “They were able to cut back when they were running with the ball and we weren’t able to cut with them. We feel that everyone has to lose some time, but this is a pretty hard time to start. The Giants, though, were a fine ball team and their comeback in that second half was the greatest ever staged against us. Ken Strong, I thought, was the best man on the field.”

The formerly pessimistic Tim Mara was jubilant after the game, “I never was so pleased with anything in all my life. In all the other contests with the Bears, I always have hoped the whistle would blow and end the game. Today I was hoping it would last for a couple of hours.” Although Halas may have known deep-down that the Bears had the better team, he was gracious in defeat, “They deserved to win because they played a great game in that second half. The only bad break we got was when that touchdown was called back in the first half. It would have made the score 17-3 and put us way out in front. My team was under a terrific strain, however, trying to maintain a winning streak which extended over 31 games. After all, we’ve caused a lot of heart-aches, so I suppose we can stand one ourselves.”

Ed Danowski (22), John Dell Isola (2), Ken Strong (50), Len Grant (3), New York Giants (1935) – Photo Courtesy of Rev. Mike Moran

Manhattan College basketball coach Neil Colhanan joined in the Giants revelry, possibly with a slight lament, “I’m glad our basketball shoes did the Giants some good. The question now is, did the Giants do our basketball shoes any good?”