The first chapter of the New York Football Giants history closed on December 29, 1963. Up until that time, one of the cornerstone franchises of the NFL, the Giants prospered on the field while they regularly struggled financially to stay afloat. The franchise nearly went bankrupt fending off four American Football Leagues (AFL) and the All-America Football Conference (AAFC), all of which placed one or more teams in the New York market. No other franchise had as many direct competitors as the Giants; 13 in all attempted to carve out their own niche in the greater New York area after Tim Mara, Billy Gibbons and Dr. Harry March purchased the rights to establish an NFL franchise in New York in 1925.

A significant number of these incursions took place during the circuit’s leanest years during the Great Depression in the 1930’s and World War II in the early 1940’s. These were times when a pro football team’s primary source of income was ticket sales. Radio and newspaper were the forms of communication and promotion, and bad weather would keep turnstile counts low.

The AAFC proved to be the most formidable foe to the NFL, and to the Giants in particular. The Maras were forced to take out a significant loan to keep the franchise solvent as escalating player salaries rose disproportionately against the modest income stream that had yet to be augmented by lucrative television money.

The decade of the 1950s was a rare period where both the NFL and Giants remained free from competition. After the New York Yanks franchise relocated to Dallas in 1952, the Giants were the lone football team in New York for eight years, their longest stretch as New York’s long pro football team.

The fourth AFL in 1960 was initially considered little more than a nuisance to the Giants, who were a star-studded outfit that regularly contended for the NFL Championship, and crossed over into popular culture with numerous players receiving advertising and media opportunities. For the first time since Red Grange in the 1920s, pro football players became household names, and the first among them were Giants like Frank Gifford, Sam Huff and Pat Summerall.

On the field, the period between 1925 and 1963, the Giants were among the NFL’s “Big Four” that dominated the gridiron circuit, along with the Packers, Bears and Redskins. The Giants overall record of 294-156-27 over 38 seasons gave them a winning percentage of 0.645. Included were 16 postseason appearances, more than any other franchise, 14 league championship games, and four NFL titles. The first championship in 1927 was played before there was a post season; the other three were all won on the Giants home fields in the Polo Grounds in 1934 and 1938 and Yankee Stadium in 1956. The Giants lost four other titles games on their home field, but established league records for attendance until the NFL moved into the enormous Los Angeles Coliseum which held over 100,000 patrons.

The ultimate recognition for the best-of-the-best is induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. The Giants were invited to play in the first Hall of Fame Game in 1962 and had three charter members in the inaugural class of 1963: founder Tim Mara, center Mel Hein and tackle Cal Hubbard. There would be many more to follow. Today, the Giants total number of enshrines of 22 rates third, behind only the Bears and Packers. Of the Giants 12 retired numbers, 10 were worn by players from this era.

Foreshadowing

Many believe the Giants demise was initiated with the trading of linebacker Sam Huff to Washington and defensive tackle Dick Modzelewski to Cleveland during the 1964 offseason. That may be true, but there were warning signs that went unnoticed, obscured by the team’s success and record-setting passing performances by Y.A. Tittle during the 1962 and 1963 seasons.

The 1959 offseason with the departure of offensive coordinator Vince Lombardi to Green Bay began a sequence of miscalculations, untimely misfortunes, unusual circumstances, and poor drafting. New York continued to succeed despite second-choice staffing and unsatisfactory talent backing up an aging, though talented and championship-hardened, roster.

Owners Jack and Wellington Mara had anticipated Lombardi assuming the head coach position when Jim Lee Howell retired. Lombardi had long been frustrated by his inability to land a head spot in the NFL, and prior to the 1958 season had been offered the head coaching job in Philadelphia. Lombardi was advised by Wellington not to take it and wait for a better opportunity. That chance came the following year, and according to Wellington, there had been an oral agreement with the Packers’ board of directors that they would release Lombardi back to the Giants when the New York head coaching position became available.

Howell stepped down from coaching after the 1960 season and moved into the Giants player personnel department. Green Bay refused to relinquish Lombardi to the Giants after he led the Packers to the NFL Championship Game that season. The Maras then turned to offensive coordinator Allie Sherman, considered by many around the league to be a brilliant offensive mind. Sherman would become the most controversial and polarizing figure in franchise history.

Sherman originally came to New York in 1949 as a specialist to help Single Wing and A-Formation tailback Charlie Conerly transition into a contemporary T-Formation quarterback. Giants Head Coach Steve Owen, while being a revolutionary genius with defenses, had dated ideas on offense and relied on concepts that were comfortable to him. Sherman was a prized possession of Philadelphia head coach Earl “Greasy” Neal as an undersized quarterback and later assistant coach. Sherman helped the Eagles become an offensive power and advance to the NFL title game in 1947. Neal told Owen, “Take Sherman as your assistant. He knows more about (the T-Formation) than anyone.”

Sherman and the Giants were mostly successful, albeit never fully committing to either Conerly or the T-Formation, over the next four seasons. A disastrous and injury-riddled 1953 campaign led to Owen’s departure. After being passed over for the head coaching positon for Jim Lee Howell, Sherman coached the Canadian Football League’s (CFL) Winnipeg Blue Bombers for three seasons. His teams featured imaginative offensive concepts with multiple men in motion that took advantage of the CFL’s more liberal rules, and qualified for the post season all three years.

Despite his success, Sherman desired to return to the NFL and accepted a scouting position with the Giants in 1957, while also coaching Conerly part-time. When Lombardi left for Green Bay in 1959, Sherman assumed the Giants offensive coordinator role. Under his tutelage, Conerly enjoyed a career year and was awarded the NFL’s MVP trophy as the Giants won the Eastern Conference title.

After Howell stepped down as head coach, Sherman signed a three-year contract as head coach of the Giants on January 10, 1961. Before Sherman became official, there were many behind-the-scenes machinations where the Mara’s attempted to extract Lombardi, who was entering the third year of a five-year contract to coach Green Bay. Once the futility of that exercise was accepted, Sherman became the eighth head coach of the Giants.

The roster Sherman inherited had plenty of championship experience. Many of the Giants starters, including the core of the defensive front seven, were on the Yankee Stadium field when they won the NFL Championship in 1956. That was also the team’s biggest problem – their best players were their oldest. There hadn’t been a rookie drafted that made an impact on the Giants since Sam Huff.

Most troubling, many of New York’s draft picks produced for other teams. Wide receiver Buddy Dial (2nd round 1959) had an eight-year career in Pittsburgh and Dallas, and appeared in two Pro Bowls. Wide receiver Bobby Joe Conrad (5th round, 1958) had a 12-year career with the Cardinals and Dallas, was All Pro once and played in another Pro Bowl. Don Maynard (9th round 1957) was a reserve and kick returner on the 1958 Giants, but he went on to a Hall of Fame career as a wide receiver with the New York Titans/Jets. In 1959 the Giants first round choice (10th overall) was used on quarterback Lee Grosscup as an heir apparent to aging Conerly. Grosscup appeared in eight games and amassed a total of 47 pass attempts as a Giant through 1961, his last year on the team. He was out of football altogether following the 1962 season.

What the Giants did do well, and what sustained them for a terrific three-year run, was execute exceptional trades. The Y.A. Tittle deal with San Francisco for tackle Lou Cordileone turned out to be a first-rate heist in New York’s favor. Soon after, a trade with Los Angeles for Del Shofner in exchange for a first round pick completed the key components of what would become a record-setting offense.

While the roster still lacked the desperately needed infusion of youth, there was no wanting for talent among the starting eleven, regardless of the dates on their birth certificates. New York’s average age was 29½ with 6½ seasons of NFL experience for their starting lineup in the 1962 NFL Championship Game versus Green Bay. The Packers, by comparison, were just under 28 years with five years of experience. That does not appear to be a significant difference on paper, but once the Giants over-30 crowd began to leave following the 1963 and 1964 seasons the decline in performance was precipitous. Green Bay’s core remained mostly intact through a run of five championships over seven years, which ultimately saw them be honored with the unofficial title of Team of the Sixties.

Duplicitous Eccentric or Misunderstood Genius?

Sherman’s first three seasons at the helm were unqualified successes. The Giants 33-8-1 record earned them three Eastern Conference titles. Despite losing all three championship games, Sherman was recognized as one of the game’s best and brightest coaches. He was voted NFL Coach of the Year in 1961 and 1962, and remains the only coach in history to have won in consecutive years. Wellington Mara quipped years later, “Allie might have been the best second choice since John Alden.”

Tittle certainly was appreciative of what Sherman meant to his career. The reborn quarterback established the NFL record for touchdown passes in a season with 33 in 1962, then reset it with 36 in 1963, during 14 game seasons. Those still stand today as the Giants franchise standard. Tittle said, “(Sherman) never looked upon the Giants as a team but as 40 men – each with a unique personality. Sherman realized early in his career that a successful club depended on the system adapting to the players, not the other way around.” The Giants were so confident in Sherman, they tore up his contract after the 1962 season and locked him up with a new five-year deal.

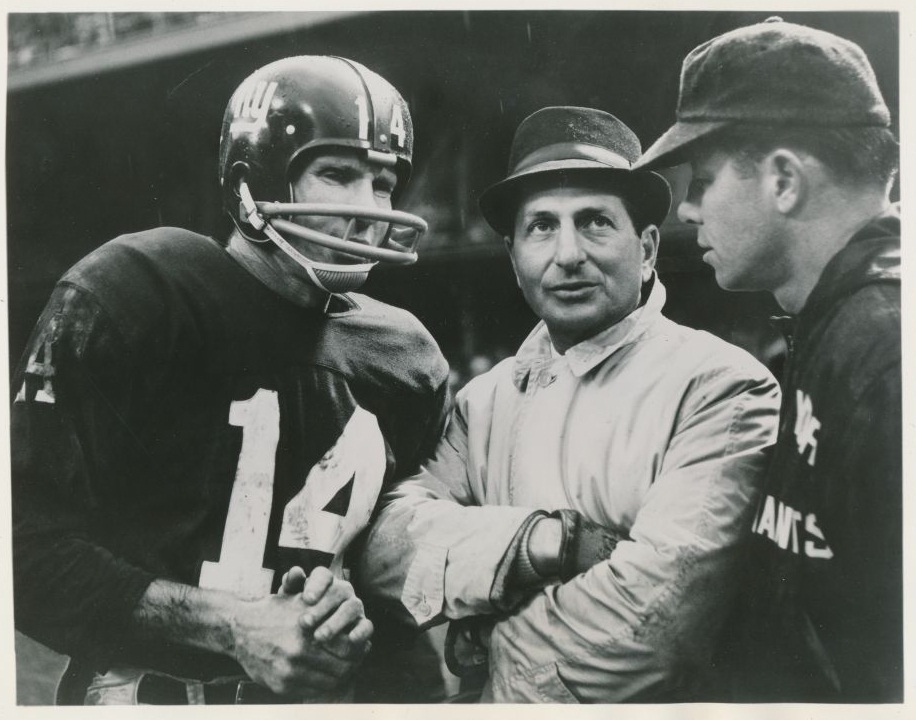

Y.A. Tittle, Allie Sherman, and Kyle Rote, New York Giants (1963)

Not everyone behind the scenes were as generous sending adulation Sherman’s way. Halfback and wide receiver Frank Gifford saw two sides to the coach: “Allie was a terrific offensive coach but not a great head coach. Allie had a good sense of the passing game, and he loved to employ it. But when it came to dealing with real players rather than with blackboard X’s and O’s, Allie’s style hurt him a great deal. Instead of saying, ‘this is the way it’s going to be,’ he tried to cajole the players.”

Defensive end Andy Robustelli described the first three years of Sherman’s tenure as “an era of agony and ecstasy for all of us connected with the Giants – the agony often taking place in our locker room while the fans were in ecstasy over the wondrous feats our team performed.

“We freely wondered whether the head coach had a hang-up about the defense, and after a while we simply accepted the fact that we would never be his favorite. It was plain to us that he couldn’t handle the defense’s notoriety. My role as a coach offered me a unique perspective as well as some agonizing dealings with Sherman. Al was not the kind of person with whom you could disagree and feel it was for the good of the team. That was a tough situation for me because I felt one of the prerequisites of being a good assistant coach was to express freely an opinion that was based on experience and knowledge.”

Robustelli placed most of the credit on Tittle. “Y.A. was more than just an efficient quarterback. His personality carried over to the field, where there was no doubt who was in charge.” (Y.A. Tittle’s Incomparable 1962 and 1963 Seasons)

Defensive tackle Rosey Grier was traded to Los Angeles after the 1962 season for John Lovetere, who was younger and more athletic than Grier, who suffered from chronic weight issues. Lovetere had a strong 1963 season but suffered a knee injury the following year and never returned to form. This was only the first of many moves that would backfire on New York for one reason or another. Wellington’s uncanny knack for getting the right player at just the right time had escaped him.

By far, the most shocking and controversial transaction in Giants history was the trading of star middle linebacker Sam Huff to Washington after the 1963 season. The grudge Huff held against Sherman eventually became a legend that took on a life of its own. In return, New York received two journeymen players, defensive end Andy Stynchula and halfback Dick James, who brought youth but little impact. Rookie Lou Slaby inherited Huff’s position as the man in the middle but only lasted one season as the starter, and two overall in New York. He was out of football by 1967.

The friction between Huff and Sherman began before the 1962 season with a change in scheme that confounded the All Pro. In the new defense, Huff was required to fill the strong-side gap between the guard and center, regardless of where the play was going. The reading of offensive keys that Huff had executed to near-perfection in the Landry 4-3 defense was now nullified after the snap. Near the end of the exhibition schedule Huff confided his discontent with defensive captain and coordinator Robustelli, who told him, “I agree with you, but this is the defense Allie wants you to play, and you’re just going to have to do it.” (New York Giants – Cleveland Browns 1950-1959)

Huff eventually voiced his dissenting opinion to Sherman, despite the predictable result being all but assured. No changes were made and the Giants once impermeable defense began to show signs of leakage. Over the 1960 and 1961 seasons, when the NFL schedule expanded to the 14-game schedule, the Giants surrendered an average of 17 points per game with the Landry-created 4-3 defense (this despite its originator now in Dallas with the expansion Cowboys). The next two seasons with the Sherman defense, the total went just upwards of 20 points per game. The won-loss record didn’t suffer as the potent Tittle-to-Shofner connection kept the Giants just ahead of the opponents on the scoreboard.

Also traded away that portentous offseason was defensive tackle Dick Modzelewski. He went to Cleveland for tight end Bobby Crespino, a serviceable if unspectacular player who remained with New York through 1968. The foundation of the Giants 4-3 defense, defensive tackles Grier and Modzelweski backed by Huff, had been gutted.

If the Giants hadn’t felt like they went into games with one hand tied behind their back going into the 1964 season, it probably didn’t take long soon after it started. The injuries that depleted the roster were symbolized in perpetuity with the crushing John Baker hit on Tittle in the Pittsburgh end zone. Tittle and fellow former heroes Shofner, Gifford, fullback Alex Webster, defensive end Jim Katcavage, cornerback Dick Lynch and cornerback Jimmy Patton all missed significant time or their seasons ended prematurely. Robustelli said with his tongue only partially in-cheek: “It seemed we won because of ‘experience’ and lost because of ‘age.’”

New York’s 2-10-2 record in 1964 was as abysmal as it was unexpected. Never before had a Giants team had a double-digit figure in the loss column, and the 399 points surrendered by the sieve-like defense averaged nearly 29 points per game. The inconsistent offense with rotating personnel was unable to bail them out this time. When the season mercifully closed, Webster, Tittle, Robustelli and Gifford all retired. It would be a long time before those shoes were filled.

Wandering into the Wilderness

New York had the first pick in the 1965 draft (which was held in November 1964). The Giants have had the number one overall choice twice in their history, and ironically, both times they selected highly regarded backs whose careers were altered by untimely and severe knee injuries. The first was Kyle Rote in 1951, and the second was Tucker Frederickson.

Frederickson was of a much higher pedigree than New York’s recent run of failed first round picks: Lee Grosscup (1959), offensive tackle Lou Cordileone (1960), running back Bob Gaiters (1961), linebacker Jerry Hillebrand (1962), offensive tackle Frank Lasky (1963) and running back Joe Don Looney (1964), all of whom were deemed questionable choices at the time. Frederickson was an impressive athlete with all of the necessary credentials. Many other teams were envious of the Giants at the time and stated they would have taken the back from Auburn given the chance. Denver of the AFL, which held its own draft the same day, inquired about Frederickson, but he told them he preferred to sign with the NFL’s Giants.

The celebration of the touted pick was short lived. Team president Jack Mara passed away from cancer on June 29 at the age of 57. The loss was devastating to Wellington, who had shared the duties of running the Giants with his brother for 29 years. Jack handled the business side and Wellington the football operations. With no succession plan in place, Wellington dutifully, if somewhat reluctantly, assumed stewardship of everything involved with the franchise. The strain of handling all aspects of the team over time impeded New York’s growth as a franchise during an era where the more successful franchises diversified and modernized their approach in areas such as player evaluation and acquisition. The Giants became stuck in what was often referred to as “old ways.”

While Wellington burned the candle at both ends, he craved a sense of stability and security after the loss of his brother. To that end, he tore up Sherman’s contract on July 26 and signed the coach to a new 10-year deal. Mara said, “The most important thing we could do was get the best possible leadership on the field. That’s why we have given Al a new contract.”

Sherman said, “I think any coach in the business would envy me today. We have the kind of ball club that can give the city what it has come to expect and want in the way of a winning team. We have the ingredients to come back quicker than a lot of people might think.”

Improve the Giants did in 1965, to 7-7 which was good for a second place tie in the mediocre NFL Eastern Conference. Veteran Earl Morrall started every game and stabilized the quarterback position. Homer Jones flashed some big play potential as a wide out and Frederickson made the Pro Bowl as a rookie. The defense continued to struggle, but the kicking game was far and away the weakest link. As a team, New York made an embarrassing four of 25 field goal attempts on the season, a figure that would have been unacceptable even in the drop-kick era of the 1920’s.

Mara reconciled that on-field problem by signing Pete Gogolak from the AFL’s Buffalo Bills to a three-year contract. That move also created a typhoon of issues for NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle, which ultimately led to the AFL-NFL merger. The two leagues agreed to have their respective champions meet in a unifying professional football title game after the 1966 season, and would follow with a common draft beginning in 1967. Teams from both leagues were also free to schedule preseason exhibition matches against one another that same year. (History of New York Giants Place Kickers: Drop Kicks, Placements and the Sidewinder)

The Chasm

The Giants 1966 preseason was an unmitigated disaster. Frederickson strained knee ligaments in a scrimmage with Green Bay and sat out almost all of the remaining practice sessions. He returned for the final preseason contest, a 37-10 annihilation at the hands of the Packers, and was lost for the year when that same knee was severely reinjured.

The season opener, a 34-34 tie at Pittsburgh, was at the very least entertaining. The New York Times likened the proceedings of the turnover- and mistake-filled game as a skit by either Laurel and Hardy or Abbot and Costello. The dour Sherman was more succinct, “Sloppy.” Statistically, New York was terribly outplayed. The Steelers had the edge in first downs 25 to eight and rushing yards 138 to 32. Big plays kept the Giants close. Despite being under constant pressure, Morrall connected with Jones twice for touchdowns – one for 98 yards, a new club record, and the other for 75 yards.

There were no such silver linings the following week. The Giants traveled to Dallas and were so soundly beaten (52-7), that the New York media for the first time since Red Grange’s New York Yankees in 1926, began to turn their attention to another team – the New York Jets and their flamboyant young star Joe Namath. The Giants two biggest problems would haunt them the entire season: a weak offensive line that provided no pass protection, and porous defense that offered no resistance and couldn’t get off of the field.

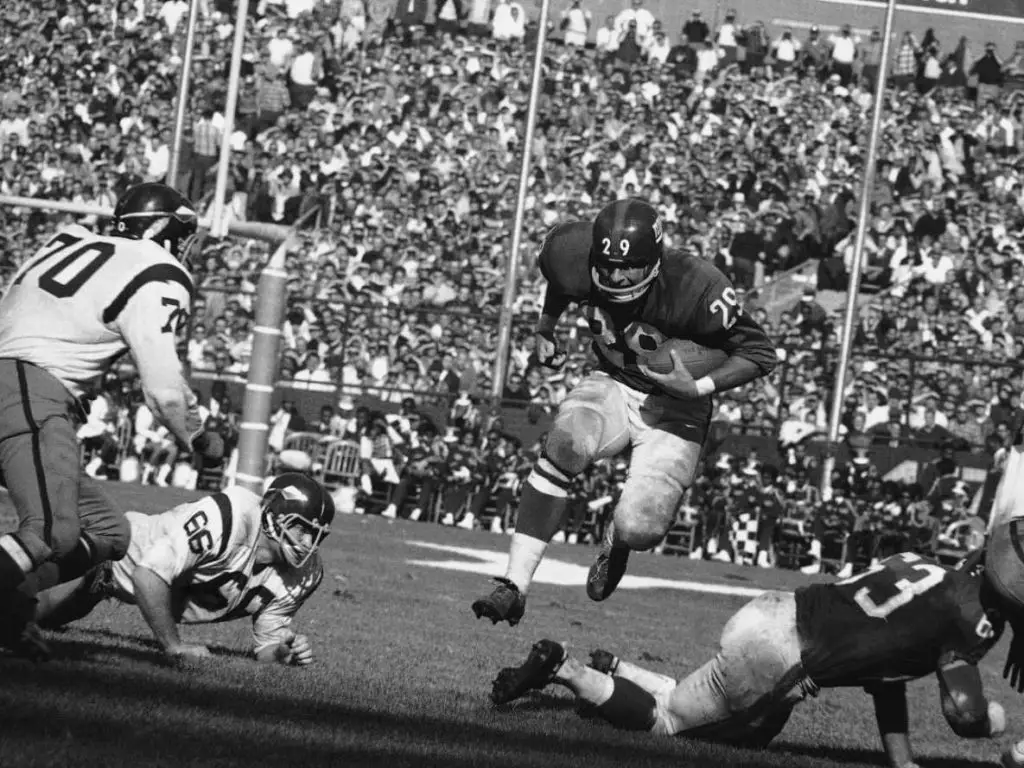

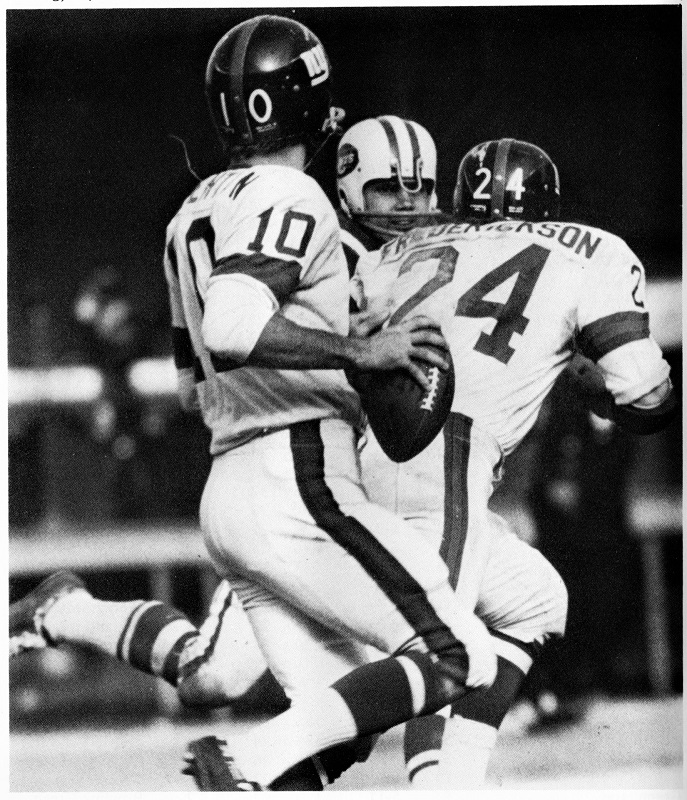

Chuck Mercein (29), New York Giants (October 16, 1966)

The points allowed in succession following the Cowboy game were 35, 28, and 24 – all losses. For one game, somehow, the Giants defense plugged the leaks in a game against Washington. New York’s front seven played as if they were inspired by the presence of old friend Sam Huff, and held the Redskins to 179 total yards and nine first downs. Giants quarterback Gary Wood, who entered the game in the second quarter, was battered by the opposing pass rush and gave way to original starter Morrall early in the fourth quarter. Morrall led the Giants to 10 points and a 13-10 win.

That was the season’s highlight, as the following week the point parade marched on. A five-game span in November and December saw the Giants surrender a mind boggling 250 points, an aggregate higher than four teams yielded over their entire 14-game schedules! In two of those games New York scored at least 40 points and still lost. To put this perspective, the average points allowed for the NFL in 1966 was 301. The Giants surrendered 501, a record for a 14-game season. The 500-point plateau has only been passed twice since the 16-game schedule began in 1978: the 1981 Baltimore Colts and the 2008 Detroit Lions.

The entire 1966 campaign was best symbolized by the November 27 game at Washington, a 72-41 loss. Three records were set that still stand today: 113 total points scored, 16 total touchdowns, 72 points scored by one team in a regular season game. The record scoring cost Washington $315 in lost footballs. Thirteen of the 14 were lost on point-after attempts kicked into the stands and the other was thrown into the stands by an enthusiastic Redskin player after a touchdown. The embarrassment reached a ludicrous level when Huff called a time out with 0:07 left in the game and sent the field goal unit onto the field, despite Washington being comfortably ahead 69-41.

Huff remained unapologetic years later: “On the field before the game, Kyle Rote interviewed me for his pre-game radio show. ‘What do you think about the game?’ he asked. ‘We’ll score sixty,’ I said into the microphone for all my friends back in New York. As we were doing our calisthenics, (Head Coach) Otto (Graham) asked me what I thought. ‘Otto,’ I told him, ‘we’re gonna kill ‘em’. And Otto, I want to ask you one more thing: show no mercy. Show no mercy to that little son-of-a-bitch across the field, because this is our day.’”

Regarding the time out call, Huff said, “While Otto was talking to (quarterback) Sonny (Jurgensen), I took it upon myself to yell for the field goal team to get out there. After the game, Otto took a lot of heat for kicking the field goal and rubbing it in. But that wasn’t Otto’s decision, it was all mine. The 72 points we scored were for a lot of people: me, Mo, Livingston, Rosey, and all the old Giants. That was a day of judgment, and in my mind, justice was finally done.”

Giants fans seemed to begin to see things thought Huff’s eyes. The derisive “Good-bye Allie” sing-along (to the tune of “Good Night, Ladies”) began to echo through the Yankee Stadium. At the conclusion of the season’s final game, Sherman required a police escort to walk off of the field through angry mobs of fans.

The Trade

The move to assuage the fan base, as well as divert the city’s fascination with the ascending Jets, was as bold as it was costly. On March 7, 1967, the Giants dealt for Pro Bowl quarterback Fran Tarkenton.

In a football sense this made sense, as the fearless and mobile Tarkenton would be able to be productive behind New York’s weak line. However, the cost of their first and second round choices in the 1967 draft, first round pick in the 1968 draft and a player to be named later was exorbitant. This signaled the start of an era Wellington later termed “the patchwork system”, a repetitious cycle of get-better-now moves that eschewed long term growth and ultimately stability. The 1967 Giants were far from a win-now team that would become a contender with the addition of a single player, even if that player was a Hall of Fame-caliber quarterback.

Wellington Mara confessed years later: “I didn’t want to have a loser while the Jets had a winner.”

For his part, Tarkenton did everything he was brought to New York to do. He gave the Giants instant credibility – on and off of the field – and stabilized the quarterback position, something that was desperately needed, as the majority of the roster seemed to be a revolving door over his tenure.

Schematically, the Giants became a diagonal offense, employing short routes and slants to get the ball out of Tarkenton’s hands quickly. He developed a certain chemistry with Homer Jones, who had his most productive years with Tarkenton. Jones set team records in 14-game seasons that stood for decades, even though his penchant for freelancing routes got on his quarterback’s and coaches’ nerves.

The 1967 and 1968 seasons were an even 14-14 for New York in the won-lost column. The difference between the 7-7 campaigns was the latter season had New York 7-3 with a chance for a trip to the post season in the realigned NFL. A four-game losing skid to close the schedule had the anti-Sherman throng at full throat again. Meanwhile, the Jets shocked the world at large with their victory over Baltimore in Super Bowl III.

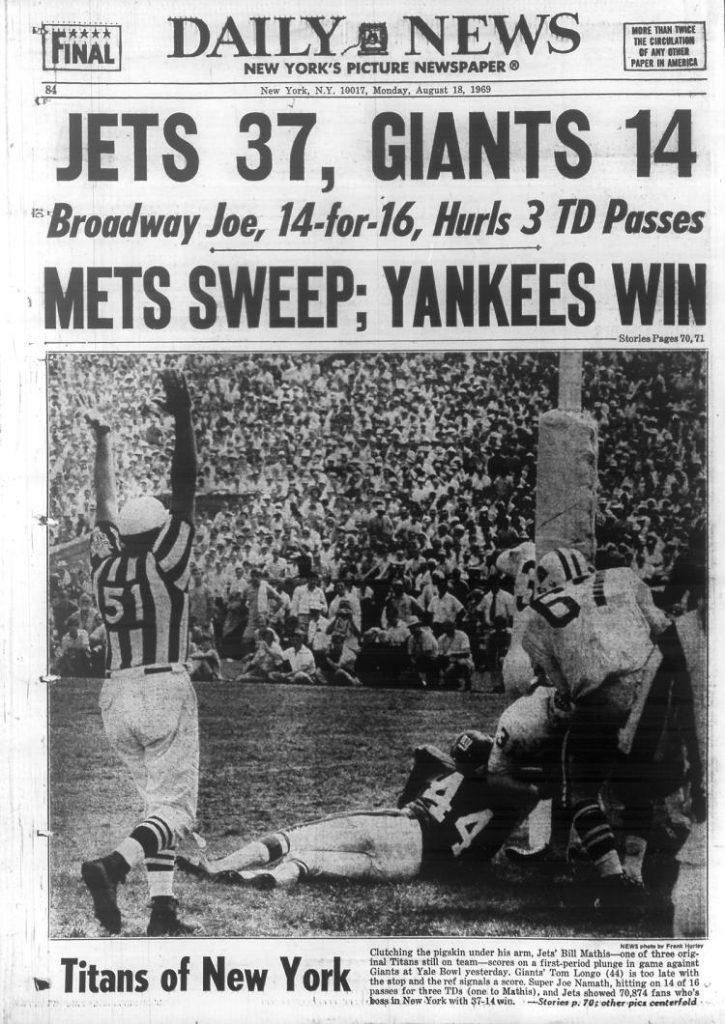

The pressure on Sherman to turn the Giants around was unprecedented, as was the hype before the August 17, 1969 preseason game between the Giants and Jets at the Yale Bowl. Giants President Wellington Mara posed alongside his Jets counterpart Philip Iselin, each holding their respective team’s helmet, as if it were Super Bowl 3½. The New York Times featured a column speculating what the world would be like if Namath were a Giant, alongside an article expressing traffic concerns of the New Haven Police Department and providing contingency plans and alternate routes. Nobody in the world could be convinced this game didn’t count for something, if not everything.

Both teams were prepared and up for the game in front of a standing room only crowd of 70,874. However, once the game started, the mistake-prone Giants must have felt helpless under the wheels of a green steamroller. Namath and the Jets led 24-0 two minutes into the second quarter and cruised to a 37-14 victory that gave them the neighborhood “bragging rights.”

Despite the one-sided score and Giants frequent ineptitude, the game remained a gritty and spirited affair. The New York Times game summary stated: “Although the contest was in truth a mere preseason game, the coaches, Weeb Ewbank of the Jets and Al Sherman of the Giants, used their personnel as though a Super Bowl were at stake. Perspiring regulars on both sides stayed in action until late in the fourth period.”

New York Giants vs. New York Jets (1969 Preseason)

Aside from botched kick returns, poor punts and turnovers, the Giants main culprit was again their ineffective defense. Namath enjoyed a pristine pocket to read through progressions and deliver strikes to open receivers. He finished the day 14-of-16 for 188 yards with three touchdowns and a clean jersey. The Giants were humbled and humiliated, and several of the Jets, including former Giant Don Maynard, said the win over the Giants was more gratifying than Super Bowl III. “The Super Bowl was one thing, but playing in the Yale Bowl before 70,000 people for an exhibition…that was another kind of Super Bowl,” said Maynard.

The dismal preseason began to take on the feel of a funeral procession as the dispirited Giants trudged along and accumulated losses. New York was 0-5 after dropping an awful 17-13 game to Pittsburgh in front of a sparse crowd in Montreal on September 22. Coupled with the 0-4 slide to close the 1968 season, the Giants had gone winless over their last nine contests. Wellington Mara’s sense of loyalty and patience had reached its limits.

The Change

The next day Sherman was fired. A sullen Mara said at the press conference, “Sometime between 2am and 6am I reached my decision. There was no straw, no camel’s back. We just weren’t winning enough football games. The sole reason for our existence is to please our fans. If we’re not pleasing our fans we’ve got to find out why.”

Sherman said, “I was a little surprised, but, heck, that’s football.”

The new coach was offensive assistant, and longtime star fullback, Alex Webster. While Sherman had five years remaining on his 10-year deal, Webster was given a two-year contract to run the team. He said, “I feel like I’m part of the family. We’ve got one of the best offensive teams in the league. We’re going to win some games.”

Mara also said there would be a new hire to work between himself and Webster. This person would focus on “evaluation, selection and procurement of players” and feature “a more distinct approach, a new outlook.” However, it would be several years before Wellington actually added this new director of football operations position.

Later Mara confided there was another candidate strongly in the running for the head coaching job “It was late in the preseason, and we didn’t have a wide choice to begin with. Somebody I would have considered very strongly was Andy Robustelli, but he was in Japan at the time and we just had to do it immediately.”

The former Giant great-turned successful businessman Robustelli years later said, “My biggest disappointment was not being made the head coach of the Giants when Sherman was fired. I was the right choice. I would have done the job.”

Behind the scenes, dissatisfaction and frustration were percolating. Wellington’s nephew Tim Mara, who had been passive with the franchise since his father Jack’s passing, began to feel the need to interject his influence. “From Allie’s later years on, I felt like I wanted to be more involved. And when we finally had to let Sherman go, I was one hundred percent for it. A change was really necessary.”

What Webster the coach lacked in organizational experience, he made up for with personal connections. Wellington said, “I thought the guy on our staff who could get the most out of the players, the guy they would most want to play for, was Alex. Alex had a great grasp of people and players and of offensive football. He was a fine offensive coach. The players knew what a great player he had been, too, and they respected him for that.”

Webster said years later, “Basically the team I took over was an average team. There were some players, but not enough. We had a few…they were offensive players, the defense was weaker. The hardest thing was taking over nine days before the season. I couldn’t put in anything of my own, I had to go along with Allie’s theories.”

Despite the sudden change and numerous challenges to overcome, the season opener at Yankee Stadium was as rousing as it was surprising. A thrilling come-from-behind win over the powerful Minnesota Vikings was highlighted by two late fourth quarter touchdown passes by Tarkenton, the second with 0:59 on the clock. The dark cloud that had hovered over the Giants since the previous November parted, and the jubilant players carried Webster off of the field on their shoulders. Yankee Stadium reverberated with cheers rather than boos and sarcastic sing-alongs.

The celebration was short lived, however. The Giants were whipped 24-0 in Detroit the following week. A seven-game losing streak in the middle of the season buried New York in a deep hole, but a three-game winning streak and a season ending win over rival Cleveland gave some hope going into the offseason.

Fred Dryer, New York Giants (December 21, 1969)

Webster’s first move to mold the Giants in his image was obtaining a reliable running back. To that end he traded the prolific, yet inconsistent, receiver Homer Jones to Cleveland for halfback Ron Johnson, defensive tackle Jim Kanicki and linebacker Wayne Meylan. The idea was to have more balance on offense, and hold the ball to keep the defense off of the field. To assist Webster with game planning and scheming, former Giants tight end Joe Walton was promoted, and he coordinated the new passing attack and based the offense around the I-Formation.

The new-look 1970 team had an up-and-down preseason, but it included a win over the Jets (who were without an injured Namath). The Giants endured a disappointing 0-3 start to the regular season and inspired little optimism. But, before going down in flames, Webster’s team started to click. Johnson had the Giants first 100-yard rushing game in three years during a win against Philadelphia. The next week’s 16-0 win over the Boston Patriots was New York’s first shutout since 1961, and the following week Tarkenton became the first Giant to throw five touchdown passes in a game since YA Tittle in 1962. Finally, comparisons to the past were favorable. After evening their record at 3-3, the first regular season showdown with the Jets took place at Shea Stadium on November 1.

Some of the luster of the matchup was missing as Namath watched the game from the sidelines in street clothes, but the demand for tickets was so strong that the Jets management installed temporary seating to meet the demand.

The Shea Stadium record crowd of 63,903 witnessed a mostly non-descript game until a fist-fight erupted between Tarkenton and Jets linebacker Larry Grantham. The Jets led 10-3 in the third quarter and just halted a Giants drive when they stopped Tucker Frederickson on fourth-and-goal from the one-yard line. Tarkenton felt he had been hit after the whistle by Grantham, and the two ignited a skirmish between the teams. After order was restored, Jim Files tackled former Giants running back Chuck Mercein in the end zone for a safety. Now with momentum with the Giants, Tarkenton exacted some revenge by hitting Johnson down the sideline for a 50-yard gain and then Bob Tucker for a 9-yard touchdown. The two-play drive following the free kick gave the Giants a 12-10 lead.

Fran Tarkenton and Tucker Frederickson, New York Giants (November 1, 1970)

Cornerback Willie Williams then intercepted Al Woodall’s first down pass after the kickoff and returned it to the Jets 29-yard line. Three plays later Tarkenton connected with wide receiver Clifton McNeil for an 11-yard touchdown and 19-10 advantage. The 16-pojnt eruption came with just 77 elapsing from the clock. The Giants added a field goal in the fourth quarter for the 22-10 final score. More importantly, the 4-3 Giants were in playoff contention.

Back-to-back come-from-behind wins at Yankee Stadium against division rivals Dallas and Washington set the Giants up for a meaningful December. The Giants had won nine of their last 10 games heading into the season finale against the Los Angeles Rams, and a win would earn their first division title and playoff berth since 1963. Their prospects looked good after Gogolak gave New York a 3-0 early in the first quarter but the game unraveled quickly after that. Los Angeles led 24-3 at the half, as they took advantage of numerous Giants miscues. New York lost five fumbles on the day and lost 31-3.

Regardless of that final game, the Giants had a lot to feel good about. The 9-5 record was their first winning mark since 1963, Johnson was the first 1,000 yard rusher in franchise history and Gogolak set a team scoring record with 107 points.

But New York soon discovered their success was fleeting. Distractions that made the action on the field seem secondary in importance were lurking just around the corner.

The Move

On March 25, 1971, to the surprise of all, The New York Times published an article stating the Giants had forged a verbal agreement with the state of New Jersey to explore future options of constructing a football-only stadium on the other side of the Hudson River.

Backlash came fast and hard. Editorials in all the area papers criticized the Giants for “abandoning” the city and accused the Maras as being “opportunists.” All of these emotionally based assaults ignored the fact that the Giants had indeed explored options construction in Uniondale and Yonkers, New York, and only after refurbishment requests to the city to upgrade the aging Yankee Stadium were refused.

The official announcement of the Giants partnership with the newly created New Jersey Sports and Exhibition Authority (NJSEA) came on August 26, and ended a summer of rumor and speculation.

Immediately following the announcement, New York Mayor John Lindsay attempted to evoke a clause in the Giants contract with the Yankees, after finally authorizing a $24 million upgrade to Yankee Stadium, to evict the Giants from the city limits. Lindsay also petitioned NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle to bring an expansion franchise to New York and demanded the Giants drop “New York” from their name.

In a public statement, an irate Lindsay said, “In taking this action the Giant management crossed the line that distinguishes a sport from a business. I am today directing the Corporation Counsel to initiate proceedings to restrict the rights of the Giants to call themselves the name of the city they have chosen to leave.”

The expansion prospect proved unrealistic. The NFL established home markets as a 75-mile radius from the location of home game sites – regardless of political boarders. Any team staging a league contest within that radius would need the approval of both the Giants and Jets. This concept also played into the Giants keeping their identity with New York after moving the short distance to New Jersey.

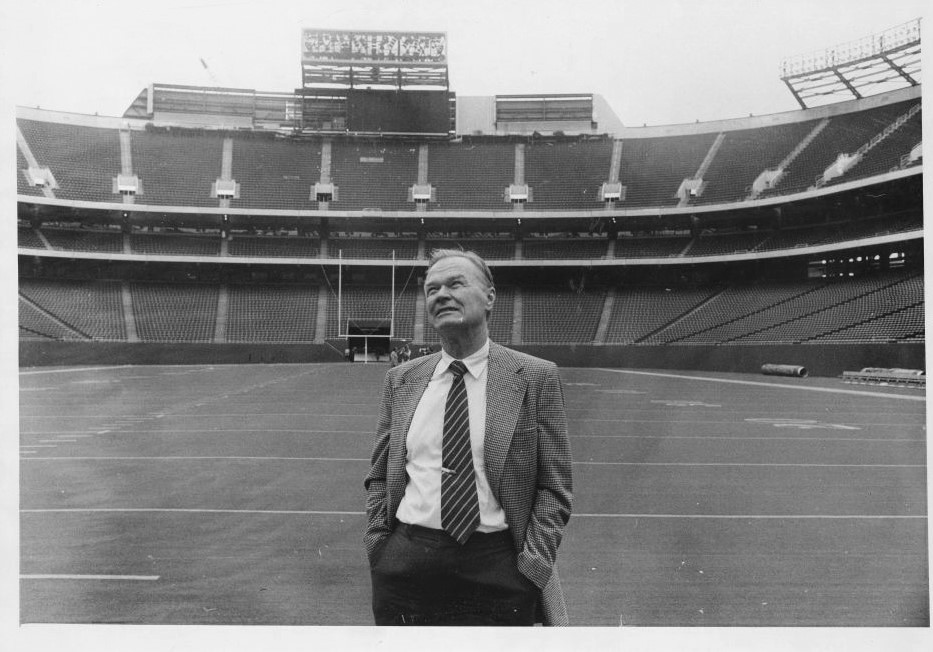

At the press conference with New Jersey Governor William Cahill and NJSEA chairman Sonny Werblin (former owner of the AFL New York Titans), Wellington Mara cited the positive aspects of the new football-only stadium: more and better seating, easy access from the highway and more parking close to the stadium. The football Giants had been perennial tenants to the baseball Giants and Yankees since 1925, and they were ready for a state-of-the-art home of their own.

William Cahill, Wellington Mara, David Werblin; Meadowlands Announcement (October 27, 1971)

Wellington Mara said: “In going around the circuit, we felt other clubs were able to take a lot better care of their fans. We had a lot of obstructed view seats in Yankee Stadium. And we had a huge waiting list for tickets. We thought if we could get better locations for more people, it was something we were very interested in.”

No doubt, part of the vitriol public officials directed toward Mara and the Giants came from the sting still felt by the departure of the baseball Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers in 1957. The financially troubled city that was struggling to compete with other markets just learned they were losing their third professional team in 14 years. Bronx Borough President Robert Abrams curtly stated, “We made them a successful operation, now they want to leave. If they want to play in a swamp, let them play in a swamp right now.”

All of this commotion obscured the actual game of football for the next several years. In retrospect, that may have been a blessing in disguise. The surprise winning season of 1970 proved to be little more than a mirage, as the 1971 Giants crumbled on the field and were a discontented rabble off of it.

Johnson appeared in only two games while rehabbing a knee injury, and Tarkenton and defensive end Fred Dyer forced their way out of New York via trades after the season. A rift between Tarkenton and Mara over a financial disagreement caused the quarterback to go AWOL during the preseason, and apparently affected his performance during what would be his statistically poorest campaign. Dryer was simply fed up with what he considered a poorly-run operation, “I had to get out of that place while I had my sanity.”

The Giants rebounded to their second winning record in three seasons in 1972, as the healthy Johnson returned better than ever and had another 1,000-yard season. However, that too turned out to be another tease. While the 1966 embarrassment remains the single-season low point for the Giants, the 1973 and 1974 seasons are the worst back-to-back campaigns in franchise history. The combined 4-23-1 record bridged the Giants exodus from Yankee Stadium – where they started the 1973 season with a win and a tie – to the Yale Bowl in New Haven, Connecticut.

Ron Johnson, New York Giants (September 23, 1973)

The Giants had explored many options for a location suitable for their temporary home games. These included Downing Stadium at Randall’s Island, Michie Stadium at West Point and Palmer Stadium at Princeton University, but all proved unsatisfactory for one reason or another. While the Yale Bowl lacked its own locker room facilities – the teams changed and showered at a field house approximately 200 yards away – the seating capacity accommodated just over 70,000 patrons.

The Giants residence at Yale featured two head coaches (Webster was released after the 1974 season), one victory (24-13 over the St. Louis Cardinals on November 18, 1973) and zero Pro Bowlers – the first time since that event’s inception in 1950 that no New York player was invited.

Linebacker Brian Kelley recalled, “My rookie year was ’73 and the first couple of games of the regular season we played in Yankee Stadium. From there, it started going downhill pretty quick. We went to the Yale Bowl. Not that it’s a bad place, but it was more like an away game, because we had to drive two-and-a-half hours from our practice fields to go to a home game.”

An Anguished Disorganization

The Giants – somewhat reluctantly and not without consternation – named Andy Robustelli as their first Director of Football Operations prior to the 1974 season.

Robustelli said of his hiring, “During the previous week Well and Tim had discussed what might be done to revive the team, and Tim suggested someone with a football background was needed to run that side of the organization. When Wellington and Jack ran the team, Well was the vice president, but in effect his duties were those of a director of football operations. When he succeeded Jack as president, Wellington thought he could continue to specialize in that area and allow Tim to take over the business side; as club president Well would continue to oversee as necessary. Those plans fell apart when everyone in the organization turned to Wellington to solve every problem.”

Wellington Mara said, “It became obvious to me that I had to step back, that I had to bring someone in to run the team. Because of the closeness and length of my association with all of the people on the staff, where I thought I was just giving an opinion, it was being taken as an instruction. It wasn’t meant to be that way.”

Tim Mara said, “I It became clear we needed a football man to run the team, a general manager. I suggested that and Well agreed with it…(Robustelli) was what I thought we needed…during that time I was still more or less dealing with the business aspect of the team.”

Robustelli said the most difficult aspect of integrating with the organization was the displacement of Wellington’s long-time friend Ray Walsh, who possessed the title of general manager. In Robustelli’s words: “In reality, he was the business manager. Unlike most general managers in professional sports, he did not deal with the players’ contracts, make trades or involve himself in any way with the football operation.” Walsh received a vice president title and continued to deal with non-football responsibilities.

Robustelli’s first major move was finding the Giants next head coach, and for the first time since 1930, a candidate from outside the Giants organization was chosen. Bill Arnsparger, the architect of the Miami Dolphins dominant defense, was a hot commodity following three consecutive Super Bowl appearances, including two victories. Arnsparger was renowned for both his tactical skills as well as his patience, a necessary trait for the massive rebuild that loomed.

Wellington Mara said, “Tim, Andy and I drew up lists (of the) men we thought should be considered as the new coach. Bill Arnsparger was at the head of all three lists.”

Once Arnsparger was on board, Robustelli got to work on a complete overhaul of the Giants organizational structure. This included everything from player personnel evaluation (which included the difficult removal of the current head of player evaluation – Jim Lee Howell), building modern training facilities (which led the forging of a partnership with Pace University in Pleasantville, New York) and right up to the division of responsibilities between the team’s two owners. Robustelli even had a hand in the Giants new look on the field, and radically changed their logo and uniforms in time for the 1975 season.

The Giants on-field fortunes were not unexpectedly familiar. The lingering effects of the back-to-back 2-11-1 and 2-12 seasons were at least temporarily assuaged after the removal of Lindsay from the mayor’s office. New Mayor Abe Beame allowed the Giants back into New York to play at Shea Stadium in 1975. Robustelli said, “Nothing ever compared to Yankee Stadium, but in 1975 any permanent move was at least a year away, and we needed an immediate psychological boost.”

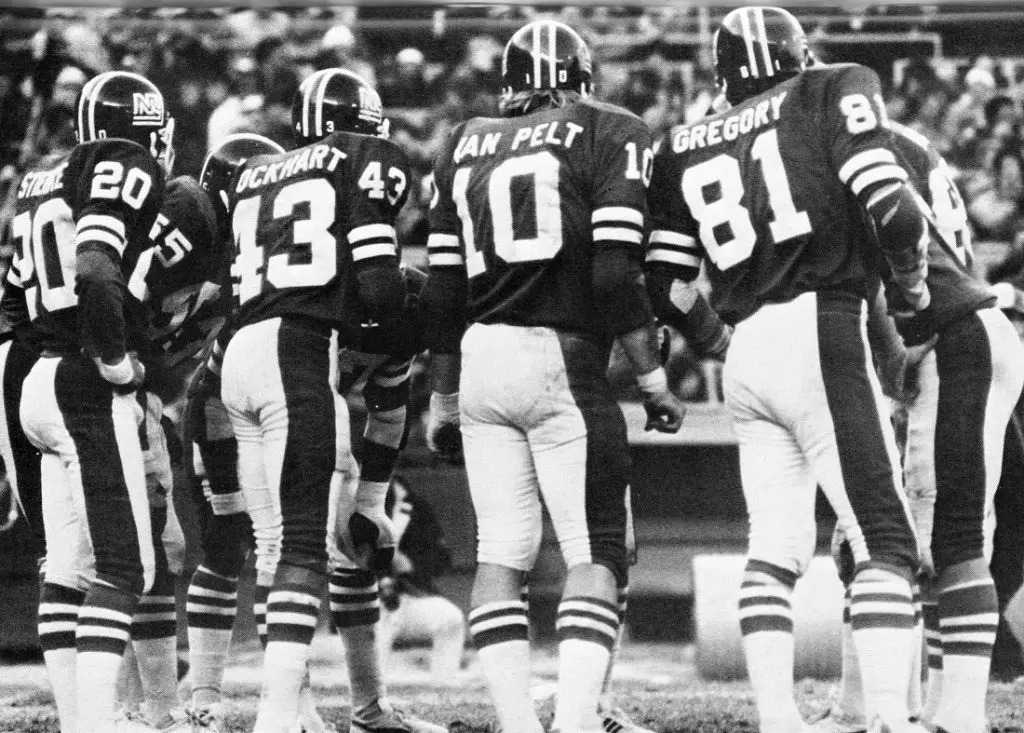

Not surprisingly, under Arnsparger’s direction, New York’s defense began to show significant improvement. Players either acquired or developed under Arnsparger included: defensive end Jack Gregory, defensive tackle John Mendenhall, linebacker Brian Kelley, linebacker Brad Van Pelt, punter Dave Jennings, defensive end George Martin and linebacker Harry Carson.

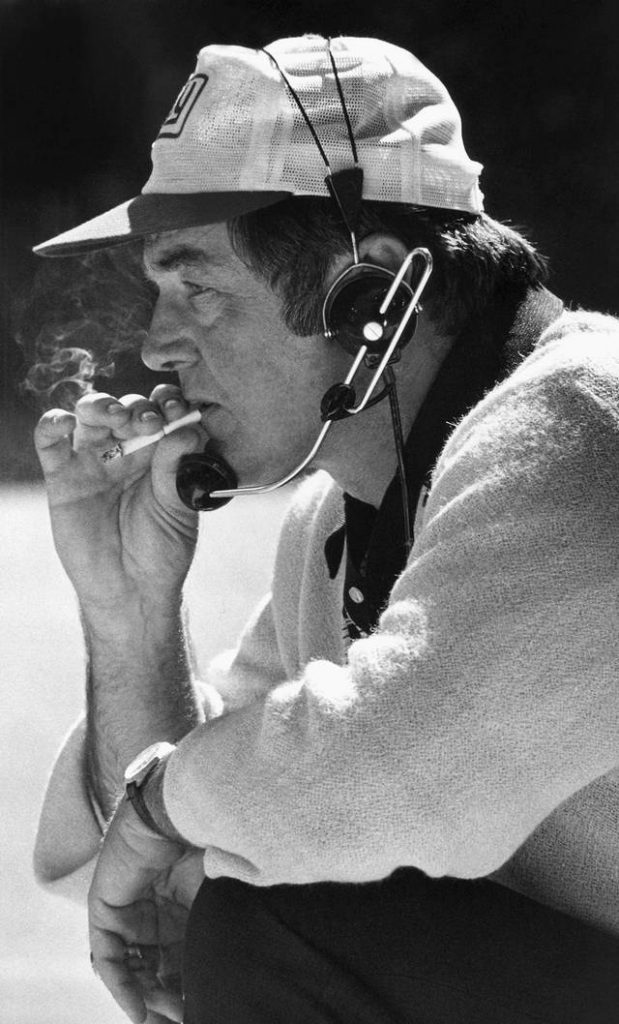

Bill Arnsparger (1974)

Unfortunately, at the same time the once-potent offense began to falter. Finding a long-term replacement for Tarkenton proved to be both difficult and costly. Norm Snead, who came from Minnesota in the Tarkenton deal, had a strong 1972 season (where he set a franchise mark with a 60.3 completion percentage) but slumped badly in 1973 while struggling with knee troubles and weak pass protection. His seven touchdown passes to 22 interception ratio underscored the need for new blood.

The Giants number one draft choice in the 1975 draft was sent to Dallas for quarterback Craig Morton, who had battled on and off for years with Roger Staubach for the Cowboys starting position. Morton possessed all the necessary physical attributes required for the position, but lacked some of the intangibles the rebuilding Giants needed to reverse their fortunes.

“We needed Morton, we had to have a competent quarterback. Maybe we paid too much for him. We probably did. But there was no choice, not really, and I’d do it again,” Robustelli said years later. “I think Morton was the right guy but on the wrong team.”

Arnsparger echoed that assessment, “It was the feeling of everybody that we had to have a quarterback of (Morton’s) capability, and we had to spend an awful lot to get him. But we were trying to do something that had to be done, but I don’t know if our team was ready for him. We probably needed a different type of quarterback, because we weren’t good enough to play with Craig.”

Robustelli said, “Craig often needed a kick in the ass to get his attention and let him know he couldn’t call his own tune. Instead of being the positive influence I had sought, the opposite occurred. I take nothing away from Craig’s football abilities, but he was not the kind of leader we sought.”

At the same time, Robustelli began to have concerns with Arnsparger’s sometime passive approach in dealing with issues. He also sometimes thought the Giants were a soft team and undisciplined team. “Bill was very stubborn about many things and very fixed in his ways, often unwilling to change or even compromise. It was exasperating at times.”

The Giants record improved marginally to 5-9 in 1975. The next desperate move caused reverberations that initiated an irreparable rift in ownership.

New Home, Old Ways

Fullback Larry Csonka, former Super Bowl MVP and associate of Arnsparger in Miami, was a free agent following the demise of the World Football League (WFL). New York’s major overseers, the head coach, general manager and principal owner were all interested in adding him to the roster for both his muscle in the run game as well fostering some as instant credibility with a disenchanted fan base.

Typical of the Giants internal climate at the time, how the Csonka signing came about is a matter of whom you believe.

Tim Mara: “We had a meeting, the three of us, and went over the players that were available.” After reviewing what were believed to be unreasonable contract demands, “…we decided not to pursue it; it might have been the shortest meeting we ever had.”

Later that week, Tim Mara said that while attending a meeting with the NJSEA, Wellington called and informed him the Giants were close to signing Csonka. Tim was incredulous, believing the patchwork system of paying for today’s short-term fix later had to stop. He attested that Wellington assured him the deal would be called off.

“But then the next call I got was that we had signed him, and we were having a press conference that night,” Tim said.

Robustelli: “Wellington became more and more enthusiastic as the negotiations progressed…Tim Mara was another matter. He didn’t even involve himself in the negotiations despite my urgings. During the Csonka negotiations, he chose to be a ‘convenient’ owner – one who was visible in the good times but never around to help make the tough decisions or take his share of the flak when (things went) badly. I believe his non participation was strategic; he left himself in a perfect position to second-guess the move, which he frequently did.”

Robustelli also said this pattern repeated itself during the renegotiation of Brad Van Pelt’s contract and the signing of first round draft pick defensive end Gary Jeter.

As uncomfortable as things were in the front office, they may have been even worse on the field during the 1976 season.

Harry Carson recalled the climate of his first NFL training camp: “Coach Arnsparger indicated that all positions were up for grabs. He wanted players to compete and didn’t care who started as long as they could get the job done. Arnsparger really didn’t have a choice; he needed players willing to shake things up as he had experienced two prior seasons that only netted him seven wins against 21 losses. He knew his ass was on the hot seat and he was in jeopardy of losing his job if things didn’t get better fast.”

The Giants began the season with a four-game road trip. Despite outplaying the Redskins for 59 minutes, New York collapsed late and surrendered the deciding touchdown with 45 seconds left in the game for a tone-setting 19-17 loss. The games at Philadelphia, Los Angeles and St. Louis were never that close, and neither was the home opener. All the compliments following the 24-14 loss to Dallas were paid to the brand new, state-of-the-art football-only stadium. Nobody had anything good to say regarding the overmatched team on the field.

“It became a growing concern, that Andy was right, when the 1976 season started. The lack of success had gotten to the point that, not that he didn’t have the respect of the players, but he couldn’t command their attention,” Wellington Mara said. “The idea of changing in midstream was not appealing, but I felt that if we continued to go downhill, some of the good young players might have been lost beyond recall.”

After closing 1975 with three straight defeats, and opening the 1976 with seven more, it had been over 11 months since a Giants team had tasted a victory. The strain was becoming unbearable.

Carson said, “The team had not won one game, and it was frustrating to lose week in and week out. I could sense that the coaches were under pressure to win…The atmosphere between coaches and players, as well as between offense and defense, was getting more hostile than earlier in the season,”

The time for change came the Monday morning after a 27-0 loss to Pittsburgh.

Arnsparger said, “…when we lost our first seven games, I came in one morning and Andy told me it was over.

Starting Over…Again

John McVay, who had head coaching experience in the WFL and had been brought to the staff as an insurance policy as a coach-in-waiting by Robustelli, was quickly promoted as head coach on an interim basis.

McVay recalled the moment: “(Robustelli) looked at me and said: ‘Bill’s leaving, and you’re it.’ Just like that. They never told me anything beforehand, never asked me if I’d take the job. I mean, they fired Bill and they decided I’d be the coach…It was the most painful, dire circumstance in which you can be cast into the job of head coach. There has been no time to anticipate it, to prepare for it, to even think about it. The shock and surprise are, well, indescribable.”

Following two more losses, McVay’s first win, a 12-9 win over Washington, was a milestone on several levels. It ended an 11-game losing streak to their division rival, marked their first win at Giants Stadium, and ended the franchise record nine-game losing streak.

Wellington Mara, Giants Stadium (1976)

Carson said, “With that first victory, you could feel the weight being lifted off our backs and especially off the shoulders of the coaches. With a win, people start to smile and feel better about themselves.”

The Giants finished the season winning three of their last five games. McVay received a new two-year contract to coach the Giants, though not necessarily on a permanent basis. McVay was seen as someone who would ascend to management and run the Giants football operations when Robustelli, who was growing weary of being caught between the bickering Maras, ultimately left to return to his private businesses.

Once again, the paramount offseason need was a new quarterback. This time around however, character was deemed the higher priority above physical ability. The Giants looked north of the border to find their man, Joe Pisarcik, a three-year veteran of the CFL.

Robustelli said, “Pisarcik was a very methodical, strong-armed quarterback who was never going to be exceptional, but he was tough and he’d fight right to the end of the game. I liked him right from the start because I thought he was the right kind of player for our situation – someone who was could hang tough and absorb some of the pounding while we bought time, upgraded other positions and got ourselves the star quarterback of the future.”

The 1977 Giants had a roster that had been largely turned over since the 1974 season. One of the pre-Robustelli players, tight end Bob Tucker, forced a trade in the middle of the season by acting out as a malcontent. His frustration was understandable – most of the promising talent on the team was on the defensive side of the ball, and the offensive line was a perpetual ongoing project. Ageless veteran offensive lineman Doug Van Horn was still reliable, but the pieces around him always seemed to be shuffling as draft picks and free agents came and went. The 5-9 season marked the fifth-consecutive sub-0.500 record for New York, but things did seem to be stabilizing. For the first time anyone could remember, there was hope heading into the offseason.

We’ve Had Enough

The 1978 Giants were 5-3 at the halfway point of the NFL’s first 16-game season. Granted, most of the wins came against the lower half of the league echelon – two of the losses came at the hands of the defending Super Bowl champion Dallas Cowboys. A three-game road trip turned into a three-game skid. Yet, the Giants still in remained in position for wild card contention at 5-6. A home victory against Philadelphia would tie the division rivals for second place.

For just over 59 minutes, that seemed to be a near certainty.

The Giants Stadium sensed all was right, to the point where many began leaving their seats to beat the traffic.

The Giants defense had just turned the ball over to the offense after stopping Philadelphia on fourth down just inside the New York 30-yard line.

Then everything began to go wrong.

On first down, Pisarcik fell on the ball for a three-yard loss, but Philadelphia linebacker Frank LeMaster blitzed and hit Pisarcik while he was lying on the ground, breaking the normal protocol on such a play. The officials stopped the clock to separate the two teams as members of the Giants, who were angered by what they believed was unnecessary roughness, defended their quarterback. Giants center Jim Clack said, “Usually, when the quarterback is just going to fall on the ball, we tell the other team to take it easy and not bury him.”

The Giants ran the ball on second down, ostensibly to protect Pisarcik from an over-aggressive defense. New York players in the huddle disagreed with the call, and told him to just fall on the ball. Pisarcik though, ran the play from the coaches as directed, and Csonka ran behind left guard for an 11-yard gain, setting up a 3rd and two. Philadelphia used their third and final time out. All that was required for New York to secure the victory was run one more play, keep the ball in bounds, and allow the remaining time to expire.

What could possibly go wrong?

The same run play was called. The results changed the fortunes of the Giants forever.

The fateful play was run with 0:31 on the clock from their own 29-yard line.

The snap from center was slightly off, Pisarcik said it was high and hit his right forearm. Unable to handle the ball cleanly, Pisarcik never had firm control as he pivoted to hand-off to Csonka, who was charging toward the hole full-speed. The mistimed exchange caused the ball to hit Csonka’s right hip and bounce away on the hard artificial surface. Eagles safety Herman Edwards scooped up the loose ball after its second bounce and sprinted across the goal line with 20 seconds left on the clock for the game-winning score.

McVay explained the controversial play call after the game, “We didn’t want to get the clock stopped by them faking an injury. Our thought was to get the first down and not have to worry about it.”

Offensive coordinator Bob Gibson said, “It was a safe play. We’ve used that play 500 times this season. It was safe. Csonka never fumbles.”

Others who were there recall the moment vividly.

Jim Clack: “Never in my life have I seen anything like it. It’d make a good movie. We’d write a good book on how to lose.”

Pisarcik: “I should’ve fallen on it. That’s what I should have done. But my job is to call the play that comes in. I don’t really have the freedom to change a play just because I don’t like it.”

Doug Van Horn: “But damn, we beat that team yesterday. Physically we beat ‘em up, only to lose in a horrible, horrible way.”

Harry Carson: “I was stunned, just like everyone else in the stadium. At the conclusion of the game I could not move. I sat on the bench for another 15 minutes staring at the ground.”

Andy Robustelli: “Using the clock in the final minutes of a game is a delicate art, even when your team has the ball and your opponents have no time outs. Plays must be called that use a maximum of time with a minimum of risk.

“However, the play that required Pisarcik to make a reverse spin – that is, he took the ball and spun in the opposite direction from where Csonka was running before wheeling around and placing the ball in his hands. I cringed when I saw that reverse pivot. I would have accepted even a simple handoff with its smaller margin of error, particularly with a back like Csonka who had done it thousands of times in his career.

“I was stunned to the point where I didn’t want to believe that the impossible had actually happened.”

New York’s post-game locker room was frenetic. The press badgered players for an explanation, but most wanted the same answers themselves. Many were too shocked to respond, others lashed out in anger. Pisarcik was coaxed out from the solitude of the trainer’s room by Robustelli and into the fray.

The next morning the decision was made by Robustelli and Wellington Mara to fire Gibson, the man responsible for the call. McVay defended his coach and offered to resign himself.

McVay was retained but fired shortly after the season’s conclusion as the Giants lost three of their four remaining games. The 6-10 record was their sixth consecutive losing season, and the fourth within that streak with losses tallying in the double digits.

Robustelli, as planned, officially resigned early in the 1979 offseason, allowing ownership to initiate their quest for a new successor. Many of the plans Robustelli had made in modernizing and restructuring the Giants organization were underway and beginning to bear fruits, especially the overhauled player development department. But he was unable to overcome the uneasiness and lack of trust between the two feuding owners who had been on non-speaking terms for nearly a full year.

The pathos became overwhelming during the Giants final two home games.

Prior to the game against the Los Angeles Rams on December 3, approximately 100 fans held an organized burning of their normally prized season tickets in a trash barrel on the sidewalk adjacent to the stadium. Their protest was, “in memory of Giant teams of the past,” fan Ron Livingston was quoted as saying in the next day’s New York Times.

Wellington Mara said, “You never like to know that what you’re trying to sell is not what they want to buy. And that’s what it means to me. You listen and you read your mail.”

The following week, during the game against the St. Louis Cardinals on December 10, another fan made sure Wellington got the message loud and clear.

Leaflets were passed out in the parking lot to tailgaters that alerted them to look skyward during the first half of the game. If they agreed with the messaged, they were encouraged to stand and cheer.

Indeed, probably the loudest ovation in the first three years of Giants Stadium occurred when the single engine plane towing the sign that read “15 YEARS OF LOUSY FOOTBALL…WE’VE HAD ENOUGH” slowly and agonizingly circled the stadium. The majority of the 52,226 fans in attendance (there were over 24,000 no-shows) not only stood and applauded, they spontaneously erupted in a thunderous chant of “We’ve had enough…We’ve had enough…” for several minutes.

After the game, the Giants humiliated principal owner Wellington Mara said he was aware of the plane, but did not actually see it, and uncharacteristically declined to comment further.

The Giants looked ahead in need of the three vital components of any successful football program: a general manager, a head coach and a quarterback. The strain they were now under would make the next two months feel like another 15 years.

************************************************************************

Sources:

“A Pedantic Professor Who Likes To Buck Long Odds”

Tex Maule, Sep. 7, 1964, Sports Illustrated

“The Giants Grow Up”

Mark Mulvoy, Dec. 4, 1967, Sports Illustrated

7 Days To Sunday: Crisis Week with the New York Football Giants

Eliot Asinoff, 1968, Ace Books

New York Football Giants 1971 Press, Radio and Television Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1971

“Scramble Back to the Deep Purple”

Tex Maul, Feb. 7 1972, Sports Illustrated

New York Football Giants 1972 Press, Radio and Television Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1973

“It’s Just One Man’s Family”

Robert H. Boyle, Sep. 25, 1972, Sports Illustrated

New York Football Giants 1973 Press, Radio and Television Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1973

New York Football Giants 1974 Press, Radio and Television Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1974

New York Giants 1975 Media Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1975

New York Giants 1976 Media Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1976

New York Giants 1977 Media Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1977

New York Giants 1978 Media Guide

New York Football Giants, Inc., 1978

The Encyclopedia Of Football – 16th Revised Edition

Roger Treat, Suzanne Treat, Pete Palmer; 1979; A. S. Barnes & Co.

Giants Again!

Dave Klein, 1982, Signet

“Up, Down And Up Again”

Ron Fimrite, Jan. 26, 1987, Sports Illustrated

Illustrated History of the New York Giants: From The Polo Grounds To Super Bowl XXI

Richard Whittingham, 1987, Harper Collins

Once A Giant, Always…

Andy Robustelli with Jack Clary, 1987, Quinlan Press

Tuff Stuff

Sam Huff, 1988, St. Martins Press

The Pro Football Chronicle

Dan Daly & Bob O’Donnell, 1990, Collier Books

No Medals for Trying: A Week in the Life of a Pro Football Team

Jerry Izenberg, 1990, MacMillan Pub Company

The Whole Ten Yards

Frank Gifford with Harry Waters, 1993, Giff & Golda Productions

“William T. Cahill: Bringing Professional Football to New Jersey”

Michael Eisen, Gameday, Sept.29, 1996, New York Football Giants, Inc.

Wellington: The Maras, the Giants, and the City of New York

Carlo DeVito, 2006, Triumph Books

Nothing Comes Easy: My Life in Football

Y.A. Tittle, 2009, Triumph Books

Captain For Life

Harry Carson, 2011, St. Martins Press

2015 New York Football Giants Information Guide

Micheal Eisen, Dandre Phillips, Corey Rush; 2015; New York Football Giants, Inc.

Official 2015 NFL Record & Fact Book

2015, NFL Communications Department

Historical New York Times searchable archive (via ProQuest)

Pro Football Reference

New York Giants Franchise Encyclopedia