Through their first ninety-nine seasons, the New York Football Giants have participated in some of the most famous games in professional football history: “The Sneakers Game” in 1934, “The Greatest Game Ever Played” in 1958, and the 2007 Giants upsetting the 18-0 New England Patriots bid for perfection among them. Perhaps because it preceded Super Bowl XXV, known as “Wide Right,” the 1990 NFC Championship Game against the two-time defending Super Bowl Champion San Francisco 49ers is often overlooked, despite the fact that it is likely the finest performance this venerable franchise has ever put forth.

The common denominator this game shared with those previously mentioned is the Giants were the decided underdogs. The 1990 49ers were not chasing perfection as the 1934 Chicago Bears or 2007 Patriots, but they were quarterbacked by a near mythical legend in Joe Montana, as were the 1958 Baltimore Colts. They were also striving to win an unprecedented third consecutive Super Bowl title.

Despite boasting a 13-3 record, New York was seen as little more than a speed bump on San Francisco’s superhighway to immortality. The Giants were injured, heading into the contest with backups at quarterback and halfback; they were past their prime, star linebacker Lawrence Taylor surrendered his once unquestioned throne as the league’s best defensive player to Buffalo’s Bruce Smith; they had peaked too early, having limped through a 3-3 finish after a 10-0 start to the season; they were simply not good enough.

What the slighted Giants may have lacked in panache, they more than made up for it with resolve. They had exited the 1989 playoffs with a startling and distasteful overtime loss to the Los Angeles Rams on their home field in a game they had felt they should have won. Since winning the Super Bowl in 1986, San Francisco had New York’s number, sweeping them in excruciating fashion in three non-strike games. Each and every time the Giants lamented the would’ves, could’ves, and should’ves. They were always this-close to defeating their nemesis, before the unspeakable transpired: defensive backs colliding in the waning moments allowing a long-distance touchdown, a freakishly close offsides flag on a 4th-quarter field goal that extended a drive leading to a decisive touchdown, or a supreme defensive effort going for naught as a frustrated offense only managed a field goal.

The 1988 loss at Giants Stadium in Week 2 was particularly galling, and ultimately cost New York a playoff berth. After Phil Simms engineered a late drive to put New York ahead of San Francisco 17-13 with 1:21 to play, Joe Montana, who came off the bench for Steve Young at the start of the second half, connected with Jerry Rice for a 78-yard touchdown pass. It was mostly the run after the catch that did the damage though, as safety Kenny Hill inadvertently collided with the cornerback Mark Collins, who had otherwise done a stellar job blanketing Rice on the day (his three other catches totaled just 31 yards).

Collins said, “The guy made one play all day. We had him covered all day. It was a perfect ball and a perfect route.”

Parcells could only concede, “Great players make great plays, and those guys are great players.”

While it may have been an embarrassment for Collins, the big play was a moment of atonement for Rice: “When I caught the ball, I knew Collins had made an effort to get the ball. I knew I had an open field. My mind flashed to 1986 when I had an open field in front of me and the ball popped out.”

The ramifications of that one play reverberated late in the evening of Week 16 when the Giants, at 10-6 needed the 10-5 49ers to defeat the 9-6 Los Angeles Rams to enter the Wild Card round of the playoffs. During halftime of the Sunday night contest between NFC West rivals, Simms infamously said to a reporter, “I’m sitting here staring now, watching the 49ers lie down like dogs.” San Francisco ignominiously went down 38-16 on their home field, leaving New York out in the cold.

All of these and more left the Giants gnashing their teeth and wanting to pull their hair out. The 49ers were the darlings of the NFL, the Bentley that rolled up to the red carpet at a Hollywood gala; the Giants were an afterthought, an SUV in the parking lot of a 7-Eleven.

When would this abominable hex, and disrespect, finally be put to rest?

As is often the case, when it is least expected.

The Prelude

The Giants and 49ers looked to be on a collision course for an unprecedented match-up in Week 12, boasting unblemished records after 10 games. The potential twenty-two combined wins between the teams, should they meet at 11-0, would eclipse the mark of 21 set by the 1934 Chicago Bears (11-0) and Detroit Lions (10-1) and 1969 Los Angeles Rams (11-0) and Minnesota Vikings (10-1).

However, respective division rivals Philadelphia and Los Angeles cancelled those plans in Week 11 with surprising upsets over their favored rivals. The hype did not wane with New York and San Francisco each charged with a loss. The intrigue simply shifted toward questions like: “Were those losses flukes? Were they looking ahead? Did they peak too early? Who was going to rebound?”

Both teams displayed sterling defensive efforts in a hard-hitting contest with San Francisco holding off a last second desperation drive by New York for a 7-3 victory. Most memorable to viewers though, was the heated jaw-to-jaw verbal exchange between Giants quarterback Phil Simms and 49ers safety Ronnie Lott.

What nobody knew at the time was that San Francisco nose tackle Jim Burt, who had played for New York from 1981-1988, was the instigator of this confrontation.

Burt later confessed, “It was my fault. Phil Simms is a very good friend, and I like him a lot, but we were out to win a football game and I will do whatever it takes within the rules. When I was with the Giants and we used to play the 49ers, Phil always thought he could throw against them if he had the time. I thought I’d spring it on Ronnie and fire him up a bit. I didn’t tell a lie or anything out of the ordinary. I thought Ronnie would have a great game if I told him, and he did. It worked. Great players have a lot of emotion, and he’s a great player. I told Simms, ‘It was nothing against you.’ I was hoping that would fire Ronnie up… I didn’t want anything to happen at the end of the game. I told [Phil] what happened. He laughed and I laughed and that was it. It wasn’t that big a deal. They got it squared away.”

Another former Giant teammate, Joe Morris, also offered some perspective on Simms underlying angst, “Phil feels like he doesn’t get the respect he deserves. Look at the people Montana has had around him and look at the people Phil had. Phil produced miracles with what he had. Montana had more talent… It’s like Phil was saying, ‘This guy’s good, but I’m pretty good too.’ Everyone wants to be respected by your peers.”

The pregame hype and fervent competition, augmented by post-game drama, made for a big night for the NFL and its broadcast partner ABC. The production boasted the second-highest Nielsen rating for a Monday Night Football game, after the famous 1985 contest between Miami and Chicago.

San Francisco finished off the regular season 14-2, losing only another game to division rival New Orleans, a strong defensive team featuring a multi-talented linebacking corps. The Giants, however, now on a two-game losing streak, appeared shaken in the wake of the loss. They stumbled their way to a 13-3 record, good enough for a division title and post-season bye, but were unimpressive in their wins and lost starting quarterback Simms for the remainder of the season with a broken bone in his foot.

With Hostetler at the helm the Giants managed three-point victories on the road against two of the league’s worst teams. Offensively, the Giants did just enough to stay ahead of the Cardinals in Arizona for a 24-21 win. The balanced offense bailed out the uncharacteristically leaky defense, which gave up nearly 400 passing yards to the Timm Rosenbach led, five-win Cardinals.

“It wasn’t letter perfect; it wasn’t a Picasso, but we’ll take it,” Parcells said.

The following week in New England, the only thing drearier than New York’s lackluster 13-10 win over the 1-14 Patriots was the weather. It rained all afternoon on the aluminum bleachers in the half-empty stadium.

“Other than a win, there really wasn’t very much we got out of this game,” linebacker Pepper Johnson said. “But it definitely could have been worse. If we had lost it would have taken a couple of weeks to get over the embarrassment.”

The only positive was that New York finished the regular season without any further injuries to key personnel and having a bye for the Wild Card round would give the team a needed opportunity to step away from the grind of the season.

“I’m concerned that we should be playing better,” nose tackle Erik Howard said. “We just haven’t been putting forth our best efforts. We just haven’t been playing consistently. I don’t think we’ve played our best in the last five or six weeks, probably going back to the Detroit game [Week 11].”

Most expected an early exit for New York come playoff time.

The Anticipation

There’s no better elixir for the doldrums than a big playoff win on your home field. Giants football remerged in their 31-3 stomping of the Bears. Strong, opportunistic defense, a dominant running game, and fourth-down excellence, hallmarks of the team that started the season 10-0, overwhelmed the visitors from Chicago.

Giants head coach Bill Parcells said, “Two weeks ago, I took a different approach to my team than I took the first 16 weeks. I was a little more aggressive with them as far as pointing out mistakes I couldn’t live with in the playoffs. I don’t necessarily think they liked it, but it got their attention.”

Their confidence boosted, the Giants looked forward to a rematch in San Francisco. The 49ers had dispatched the Washington Redskins 28-10 in their playoff opener.

Immediately, all thoughts dialed back six weeks to the intense Monday night clash.

“We felt they were the best in the West. We felt we were the best in the East,” said Giants defensive end Leonard Marshall. “It’s a familiar type of feeling to ’86. In ’86, we came off a big win against the Niners going into a championship game against the Redskins, who we had beaten twice. Now we’re coming off a big win against Chicago going against the 49ers, a team we felt we should have beaten Monday night. More than having to prove something to someone else, we have to prove something to ourselves.”

“It was a physical game,” recalled 49ers defensive end Kevin Fagan, “We were sore around here for several days. It felt like a season-ending game. Guys knew they were in a football game.”

Giants halfback Ottis Anderson, thrust into a starting role after Rodney Hampton broke his leg in the Bears playoff game, discussed the Giants offensive frustration, “The intensity of this game will be higher than the first game. That day, we didn’t execute well. Running and passing success, short-yardage, goal-line, none of it was there. Everything we did, they had an answer for.”

New York’s offensive coordinator Ron Erhardt echoed the rued missed opportunities, “The game worked out the way Bill likes to play. We were down 7-3 going into the red area. If we do our job and score, we win 10-7. If we’d done our job, that’s the way the game would’ve gone.”

Contrastingly, New York’s defense oozed confidence, as they felt they had played their best game of the season that Monday night. In fact, much of the week’s chatter leading up to Championship Sunday was centered around how the Giants were able to hold San Francisco to a meager seven points, and were they capable of repeating that performance?

“We played well enough last time to go into this game with a lot of confidence. I left the field with a very good feeling about how we played. We just ran out of time,” said linebacker Gary Reasons. “We’ve got another 60 minutes to get going again. So, we’re gonna rock and roll.”

Safety Greg Jackson felt similarly, “There’s no doubt we’re confident. We know we can win the game. It’s just a matter of eliminating mistakes, getting the breaks. We’ve been just one play away.”

Linebacker Pepper Johnson was focused on the opportunity for redemption, “It’s been more than just a rivalry. Those guys have been finding a way to beat us in the waning moments in the last four games. You can only get knocked down so much. You have to fight back.”

Putting emotion aside, there was detailed analysis on how the Giants defense was able to accomplish a near total shutdown of the 49ers offense.

San Francisco receiver Jerry Rice noted the physicality of the Giants defense and how they operated incongruously to the rest of the league: “The only thing about the Giants is they get a different scheme almost. They’re really going to be physical. The majority of the teams whenever they play nickel, they’re not going to bump you as physical. They’re not going to try to throw the timing off. They’re just going to try to disguise everything. The Giants did the opposite… Every time Joe dropped back, he had a lot of pursuit. Everything was completely off. If Joe doesn’t get the time, he can’t pass the ball.”

New York’s defensive coordinator Bill Belichick marveled at the maturity of San Francisco’s scheme: “We tried to take away [Montana’s] first read, and we did it pretty well. That gave more time for the rush to get to him… With the 49ers, they have been in their system so long they’ve seen just about everything they are going to see. They know how to deal with just about any problem they face without having to make major changes in that offense. You are not going to chase them out of their offense by putting another defensive back in the game. They have a philosophy on offense just like we have on defense. You’re not going to get us to change the things we do by putting an extra tight end in there.”

Belichick’s players expressed utmost confidence their coach and praised his diligence as being a major factor in their success.

“I learned so much from Bill Belichick,” safety Greg Jackson later said, “He always prepared you for each and every game and gave you tip sheets and everything… We wanted [Montana] to check the ball down a lot and try to cover their receivers on curl routes and take those things away. We knew if we could pass rush, we could definitely get to Montana and make him uncomfortable. We tried to close the middle up on them, the deep middle, and make them check the ball down a lot. We just made the looks a little bit different for him than he was used to seeing.”

Linebacker Steve DeOssie described the insight the players received, “For our defensive game plan, we were told that two-thirds of the catches their receivers made, whether it was the tight ends, running backs, receivers, whatever, would occur in a certain, easily defined area and that they got that receiver there through a thousand different formations. There were a hundred different personal groups and fifty types of motion. They told us that we shouldn’t get overwhelmed by all the different looks that we were going to see on the field every single time, the 49ers just want you to think about a thousand different things before they do it. They want you to sit there and think about what’s the formation. Once we saw film that week, we knew they were absolutely right.”

San Francisco head coach George Seifert spoke glowingly of New York’s defense, “They’re extremely well-coached and as fundamentally-sound as any defense I’ve seen play. I am kind of in awe of the technique of their players – how specific it is and how well-coached it is.”

The Motivation

The incentive of the Giants and 49ers was as different as the coasts they represented. The Giants strived for respect and redemption. Despite playing well enough to win in recent meetings with their rival, they came up short every time. They were also sick and tired of the inescapable catch phrase of the 1990 season – “three-peat.” The two-time defending champion 49ers desired immortality.

“Everybody is talking about us scoring a lot of points against the Giants, but I’d take another 7-3 win any day instead of us scoring 30 points and losing,” Montana said. “If they want to take Jerry Rice out of the game, then it’s up to everyone else to look around and take advantage of that. We really are a team here and not a collection of individuals. We are very close to a goal and dream that we set last year after the Super Bowl; that is very exciting. To win three straight Super Bowls would be a tremendous achievement.”

The earnestness because of the previous meeting was addressed by 49ers defensive end Pierce Holt: “There is a rivalry here [with the Giants]. In the last game, it was as intense as it gets. Every play was a battle. You had to play solidly on every down. Now the stakes are even higher.”

Belichick expressed a bigger picture view of the impending showdown: “These are the kinds of games you live for. It’s taken us four years to get back to the championship game. All the seasons of work, all those hard-fought games were just for the opportunity to play in this game. It’s not just another game.”

New York’s nose tackle Erik Howard had his own a personal take, “I grew up out there in the Bay Area. That was a big deal for me to play in my hometown.”

Giants’ cornerback Perry Williams noted the physical challenge of facing the 49ers, “It was always a dog fight. You knew it was going to be a long, drawn-out, hard-fought battle. With them, it was always survival of the fittest.”

San Francisco linebacker Bill Romanowski agreed, “You knew it was gonna be a who-was-going-to-beat-the-crap-out-of-who? kind of game. Every time we played [the Giants], that’s what it was like.”

New York defensive end Leonard Marshall spoke for all his teammates, “We wanted to go out and prove to the 49ers that we were just as good if not better than they were. And we knew we were a better team than the team they beat on Monday night. We just had to go out and prove it to them.”

For 49ers linebacker Charles Haley the game wasn’t as personal, “We are following a dream, to three-peat. We can capture a part of history. If we win the Super Bowl, even if I never play another down of football, I know I will have been part of a history-making achievement.”

Howard felt impelled to derail that dream, “I feel it’s my obligation to history not to let these guys three-peat. It’s like they’re walking six inches above the rest of us. Their feet never touch the ground.”

Giants defensive end Eric Dorsey felt there was an inequity in the perception of the two teams, “I’d like to think the Giants have some mystique too. We’re not playing for a three-peat, but we’ve been to the Super Bowl before. They’ve got to fear us as much as any team around. Why go out there if you think you’re going to lose?”

New York linebacker Carl Banks relished playing the underdog role, “We’re coming to play, regardless of what people expect. We have our own expectations. It doesn’t really matter what’s said in the paper or what the point spread is.”

Lawrence Taylor respected his opponent without putting them up on a pedestal, “They’re still the best team in football until they’re beaten. We feel if we play our game, play intense football, we can beat the 49ers.”

Teammate Gary Reasons saw a potential thread in the post-season tree, “I like this game because there are three teams that beat us this year. Philadelphia, and we beat them. The 49ers, and we have a chance to beat them. And, unless I see it differently, we’ve got a chance to see Buffalo in the Super Bowl. If we put all of those together, it would be a very satisfying championship for us. Not that I’m looking down the road. But I’m just trying to put this in perspective. This is our next opponent. The road to making it goes through San Francisco.”

The Strategy

Both defenses disrupted the opposing offenses during the Week 13 contest. What would change and what would stay the same in the rematch? Insiders and outsiders offered a variety of thoughts.

Seifert discussed a recurring theme, that the 49ers played against type and limited themselves by staying too close-to-the-vest, “We went into that game with somewhat of a conservative attitude and the idea ‘Don’t make any mistakes.’ [The Giants] were a very good team on capitalizing on mistakes and coming up with big plays defensively and controlling the ball. So, we went into that game with a certain mindset. It may or may not be the same going into this game.”

Belichick said past success has no effect on the upcoming game, “It’s like a division game. We’ve played them each of the past three years and now twice this year. They know our personnel; they know our system. We know their personnel; we know their system. Sometimes it’s a plus, sometimes you can’t stop them. I’m not worried about what we did last time. What we’ve got to do is more than they do, however much that is. Whatever they do, we have to do better than that. That’s how you win football games.”

Giants safety Dave Duerson felt similarly as his coach, “[Montana] never really got into a rhythm. We were able to upset some of the timing between Joe and his receivers. That’s what football is, it’s chess. The problem is, we can go in with the exact same game plan, they can do the exact same thing, and it still may not be the same game. That’s why they say, ‘On any given Sunday.’”

Reasons detailed the challenges of facing San Francisco, “Joe reads defenses very well. He reads the blitz very well. He knows where his receivers are going to be. He doesn’t waste any time. As soon as he drops back, on his third, fourth or fifth step when he plants that back foot, the ball’s coming out of there. Very rarely are you going to catch him off guard and surprise him with a rush. The best way to contain Joe Montana is to have tight coverage on his receivers as they come off the line, whether you’re playing them man or zone, and have a coordinated pass rush where you’re putting pressure on him, and you don’t give him a lane to step up and throw. If you take away his first and second receivers, he’s gonna check his third and fourth receivers. But by then, hopefully your pass rush will have penetrated and pushed the pocket enough to make a play on him. It’s not easy to do.”

Howard added, “You have to pressure [Montana], put some hits on him. He doesn’t like to get hit. He’ll throw the ball before he wants to sometimes, even if there’s nobody to throw to.”

Belichick expressed, however, it was more than just design that made San Francisco dangerous, they possessed a wealth of individual skill, “They have so much talent across the board… there isn’t much margin for error against them. You have to win every match-up because just one or two breakdowns will result in a completion or good run.”

San Francisco offensive coordinator Mike Holmgren praised a particular position group on New York’s defensive unit, “Their linebackers have maybe more the size, speed and talent than any group in the league. So, they are able to use them so many ways that you never know what to expect. Every time you think you what they’ll do, they surprise you.”

San Francisco guard Harris Barton was confident in facing anything New York might throw at them and looked forward to the challenge, “We see so many different types of blitzes and so many different types of schemes to try to get to him quick. We did a pretty good job of adjusting to it. We didn’t give up as many sacks as last year; we threw the ball a little more, and what suffered is our running game. But the most important thing is protecting the quarterback. Last time, [the Giants] defense really stuffed us. They’re a hard-nosed team to play. It’s always a violent game with them, but it’s a good type of game to play.”

Rice mentioned a single player who gave him problems, “I caught one pass [in the Monday night game], and they defended me really well. So, this weekend is going to be a test for me. I’m a little ticked off right now. When I went back and watched the films and everything, there were some things I didn’t do. I pride myself on doing my best job when I’m out there, and in that particular game I didn’t play well… I think we came out a little too conservative. This time we’re going to come out and be a little more aggressive and really give the receivers a chance to get downfield and make some plays… [Mark Collins] is really physical. He knocked me around a little the last time, and I got to do something to really counteract that and make plays.”

Parcells agreed with Rice on the possible strategy the 49ers could deploy to score more points, “If anything, they’ll try to spread us out a little more because they have access to more wide receivers [Mike Sherrard came off IR]. Their horizontal passing game philosophy works so well only because you have to respect their deep threats in Rice and Taylor. You have to be careful about that.”

Holmgren even hinted as much, particularly in the much talked about red zone, “If you can’t stretch them vertically, you try to stretch them horizontally to create holes between people instead of behind them. When it gets down in there, it gets harder. The defense can use the back line.”

Offensively, there was a significant change for the Giants. Simms was officially placed on the injured reserve list during the week, ending any speculation that he may return during the playoffs. For better or worse, New York was riding with Jeff Hostetler at quarterback. Additionally, Hampton’s broken leg created more flux regarding the Giants backfield. Presumably, Anderson would start, but others would also have to bear an increased workload.

“The problem is to enhance things to make the most of [Hostetler’s] ability,” said Parcells. “If he can roll out, you don’t just tell him to roll out. You design a couple of plays to take advantage of that ability. The big thing is to be mentally prepared and know your game plan. Then you let things fall into place. I wouldn’t say we’re brand new on offense, but I would say we have some things we didn’t have the first time that the 49ers have to worry about.”

Seifert offered his assessment, “It’s a different style of game now. I consider us a disciplined defense, but we’re going to have to be even more so in this particular game because of the style quarterback we’re facing. They have used [Hostetler] to attack the corners more. That’s because of his ability to run. But his ability to run doesn’t have to be attacking the corner with a play-action pass. He can drop back and find a crease and run up field after that.”

Meanwhile, with a playoff victory under his belt, Hostetler sounded confident, “I think I’m more relaxed. I’m really focused on what we’re trying to do. I feel really comfortable with some of the things we’ve put in for this game.”

Lott noted there did not appear to be any drop off with a backup running the offense, “[The Giants] offense has moved the ball regardless of who is at quarterback. [Hostetler] runs the offense as well as Simms.”

Giants guard William Roberts wasn’t concerned about who he was blocking for, “All year long we’ve been rotating backs in and out. It’s not a surprise that those guys will have to carry a bigger load. Hampton’s a big loss for us, just like Phil is, but we can’t dwell on that. You have to look forward and the ones that are filling in have to come through.”

Parcells agreed, “I think you’ll see some kind of mixture with the backs. What gives us the best chance to move the ball… I think we have an opportunity to move the ball against them. We moved the ball pretty decently against them last time. We just didn’t produce in the red area. We just need to score more points than we did last time. We want to keep the ball away from them as much as possible, but not at the expense of scoring ourselves.”

Anderson chimed in on the workload balance for the backs, “The burden hasn’t always been on me, not really. It’s been collectively on all the running backs. I think we’ve all responded well so far. I have good memories of last year when I had to carry a lot. I always look for an opportunity to run. But we have so many good backs that we can run them all.”

New York fullback Maurice Carthon preferred Anderson as the featured back, rather than backfield by committee, “O.J.’s best when he’s in a lot. He gets better the longer he keeps going. I’ve noticed every time Ottis was in the game, and he played two or three series and stayed out two or three series he wasn’t as effective… He’s ready for the challenge. You’ve got a guy like Rodney, he’s a No. 1 draft pick. Everyone knows Rodney was going to come in and play. But O.J.’s been a valuable player for us. If anyone’s going to take us there, O.J. will.”

Romanowski reflected on the 49ers preparation years later, “We didn’t know a lot about Jeff Hostetler. There wasn’t a ton of film on him. We couldn’t study a whole season of game tape on him. So, we approached it like we were playing a Giants team that was manned by Phil Simms. We thought they would pound the football. They weren’t going to have the quarterback try and win the game for them.”

The Predictions

Recent history favored San Francisco.

The 49ers entered the game not having allowed a TD in their last three NFC Championship Games [1984 defeated Chicago 24-0, 1988 defeated Chicago 28-3, 1989 defeated Los Angeles 30-3]. In fact, their defensive excellence spanned 13 consecutive quarters of championship football. The last touchdown San Francisco surrendered came in the third quarter of the 1983 championship game at Washington.

Overall, the 49ers had won seven consecutive post season games by a combined score of 236-64. The average margin of victory was an astounding 34-9.

The high-profile contest with multiple story lines drew opinions from everywhere. Not surprisingly, most favored San Francisco to further their bid to three-peat, but there were those who gave New York at least a chance.

Former 49ers head coach and current television analyst Bill Walsh was objective, “It’s going to be tough. The Giants are a physical, strong team and will come out and play with a lot of confidence. Both teams have a better feel for each other and what the other team can do. I think the 49ers are going to have a much better game plan. I think they’re going to come out throwing right away and not play around. They’ll throw the short, quick passes before the Giants can get to them. The Giants have to control the ball on the ground with their running game and at least get good field position before they have to punt or score. Hostetler is a fine runner and I think he can make some plays that Phil probably could not have made. An extra first down here or there is what can keep an important drive alive. I’ve always had great respect for Phil Simms, but the Giants haven’t lost a beat with Hostetler.”

Washington head coach Joe Gibbs, whose Redskins went a combined 0-4 against the NFC Championship combatants, gave the edge to San Francisco’s home-field advantage, “[The 49ers] are awful good. They have a lot of people to get to you with. But the Giants are capable of beating them. The Giants can beat anybody because their defense is dominating. I think these teams are so evenly matched that if they played on a neutral field, they would come out dead even. But in a championship game, the crowd is going to be cranked up. It was tough for us to hear. It’s tough to play in those conditions and beat somebody at their place.”

Los Angeles Rams defensive coordinator Fritz Shurmur highlighted the diversity of San Francisco’s offensive arsenal, “[The 49ers] have always had plenty of weapons, but what they’re doing now with their tight ends is special. Everybody knows about Jerry Rice and John Taylor and Roger Craig and the others as receivers. But now they’ve got those two tight ends who they rotate. Sometimes they play them together. When you’ve got two tight ends like they have and one of them is always fresh, and then you throw them into your mix, well, it’s another dimension for them. They complement everything in that offense and makes them even tougher.”

Chicago head coach Mike Ditka gave the impression of bitterness after his Bears recent loss to the Giants the previous week, “No one’s going to beat the 49ers. The Giants, first of all, they didn’t sack our quarterback. I don’t think their pass rush is good enough, and I don’t think they can cover well enough. Put [Giants cornerback Everson Walls] in man situations, which he’ll have to be in Sunday, they’re going to chew him up. They’ll find out he’s not what he used to be. They’ll break him with the counter routes.”

Walls, however, had bigger things on his mind than what Ditka thought of him, “Each time I play [the 49ers] I think about that play [“The Catch” in the 1981 NFC Championship Game], no doubt about it. Stepping in Candlestick gives me a feeling of alertness and intensity because I never want to be caught in that position again.”

“Nobody thinks we’re going to win,” Carthon said. “You’ve got a chance to redeem yourself, to prove a lot of people wrong. And you’ve got a chance to go to the Super Bowl. What more could you want in a game like this, especially if the deck is stacked against you?”

“We were riding house money,” Giants center Bart Oates later recalled. “We were going up against a team that was coming off back-to-back Super Bowls. We’ve got a backup quarterback and the oldest starting running back in the league. What are we supposed to do? We got no respect at all.”

Parcells liked his teams’ mindset, “I think the attitude of the team is simple – if we play our game, we can beat them. But until someone beats them, they are still the champions. They have a sophisticated passing game. They have one of the best, if not the best, quarterbacks to have played the game and one of the best receivers to have played the game. They’ve got other people doing well. But if we play Giants football, which is intense football, and if we can run the football, we will beat them.”

Lawrence Taylor believed his team was ready for the challenge, “The guys practiced what they preached all week. It’s gratifying when you find out that when you put your mind to it and act on it, you can play well. This week, we’re looking for quality defense again. A couple of years ago we got into a shootout with the 49ers and lost. This year, when it was a low scoring game, we lost. They find a way to win games. The Giants have to find a way to win games.”

The Game

The intense interest in the game was evident by the standing-room-only crowd of 65,750 that packed Candlestick Park. The voracious gathering, second largest in 49ers history, was unanimously in favor of the home team, as nary a hint of blue was to be seen in the grandstands.

After the 49ers won the coin toss and received the kickoff, the first change in Belichick’s plan was revealed. Having previously radically changed the Giants defensive front to a 4-3 to control the run-heavy Bears, the front seven returned to the familiar 3-4, but with a few twists.

Looking to maintain size in the three-man line, Howard was shifted to left end with Mike Fox starting at nose tackle; Marshall remained at his normal right end spot. Behind the line, Gary Reasons received the starting nod over DeOssie, as Reasons was more adept in coverage than the run-plugging DeOssie. In addition, strong side linebacker Carl Banks would start and play the whole game. In the Week 13 match-up, he played sparingly in his first game back from a lengthy absence recovering from a broken wrist.

CBS broadcaster John Madden explained what was going to be different about the two teams’ approaches, “The last time they played, the 49ers thought they were too conservative. Mike Holmgren said what he did is if Montana was throwing in rhythm and there wasn’t anyone there right now, he would have him just throw the ball away. Today, he said they’re gonna open it up, spread it out, and he just told Joe, even though he hasn’t practiced in the last two days [because of the flu], ‘just do what you do best.’… Last time, what the Giants did on defense, is they used five defensive backs, they were in nickel the whole time. This time they’re playing Carl Banks here [over the TE], this is where they played [Greg] Jackson last time. So, now they’re playing their regular three linemen and they’re playing Gary Reasons because he’s a better pass defender. They’re not playing nickel on regular downs.”

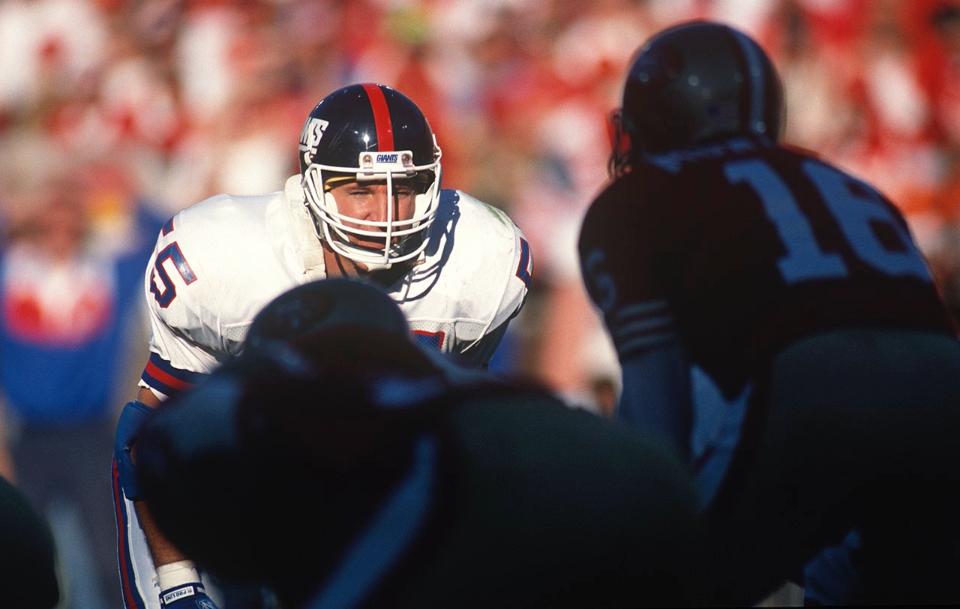

Inside Linebacker Gary Reasons

The 49ers intention of spreading the Giants defense horizontally to create more passing lanes appeared to work as they moved the ball 44 yards over 10 plays, seven of which were passes and all three first downs were achieved through the air. Tellingly, Rice caught only one pass and it was for a loss of one yard.

Madden elaborated between plays, “The Giants defense, they all tackle well… Mark Collins is a very confident guy. He believes the way you play Jerry Rice is you play against him physical; you make everything physical. If you catch it, OK, but you’re not gonna make any yards. Mark Collins is a very good corner, a very good cover guy, but he’s a very strong player, a very physical corner.”

The tenth play of the drive was a 47-yard field goal by Mike Cofer to give San Francisco a 3-0 lead at 9:59. Despite surrendering yardage and points, New York’s defense adjusted quickly to the 49ers scheme by pressuring Montana with new-look blitzes that forced errant throws and check-downs for minimal gains.

The Giants offense answered with three points of their own, but how they did it was quite different than what many expected from their normally plodding attack. Over the 15-play advance that consumed nearly half the quarter (7:18), the Giants passed the ball eight times versus six runs. Dave Meggett was the featured back on the first three rushes, highlighting his elusiveness and speed over Anderson’s straight-line power. Carthon ran the ball once, before he and Meggett combined for the first half’s most startling play.

Jeff Hostetler

Once inside the much-discussed red zone, which had begun to take on the mythos of the Bermuda Triangle for the Giants against the 49ers, New York’s solution to reach the end zone was to go deep into the playbook for the unexpected. On first down at the San Francisco 11-yard line, Hostetler pitched right to Meggett, who ran toward the boundary and then pulled up and floated a perfect spiral into the waiting hands of an open Carthon in the back of the end zone. But Carthon let the ball drop to the turf.

“It was a good pass and it just dropped,” Carthon said, “There’s nothing you can do about it… You have to take it one play at a time.”

Two more incompletions preceded kicker Matt Bahr’s first field goal of the contest, making the score 3-3 at 2:41. Despite failing to solve the 49ers red-zone defense, New York achieved other goals. They moved the ball well by mixing in a variety of passes and wide runs and kept Montana and the San Francisco offense on the sideline for an extended period of time.

The Giants defense quickly dispatched San Francisco’s ensuing possession, forcing a punt in three plays as the first quarter quickly ended. Madden said, “We were talking to Bill Belichick last night and he says that you have to take away Rice, you have to take away [John] Taylor, and if Montana’s gonna beat you then he’s gonna beat us with a guy like [Tom] Rathman catching it. He doesn’t feel that Rathman and [Brent] Jones catching the ball can beat you. He feels that guys like Rice and Taylor are the ones you have to take out of the game.”

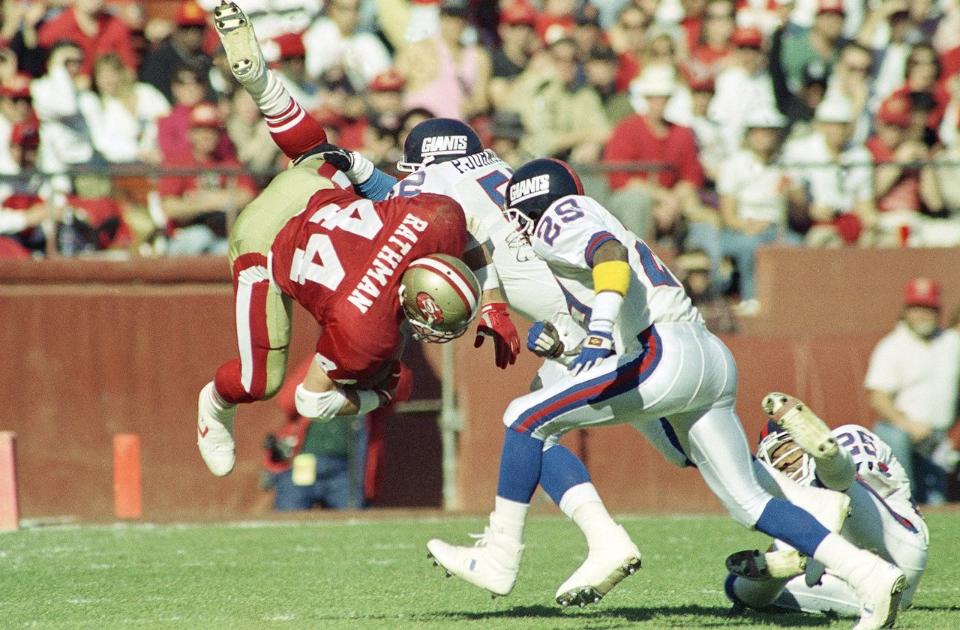

Pepper Johnson and Myron Guyton attack Tom Rathman

Duerson noticed Montana looking shaky early, “After the second series, when he left from under center, he was already passive, you could see it. He was expecting to get hit. Even when he handed off, he was flinching.”

New York opened the second quarter with a three-and-out of their own, but not without a moment of drama as Madden and broadcast partner Pat Summerall pondered the possibility of the Giants going for it on fourth-and-one near midfield. A week earlier the Giants stunned the Bears four times on fourth down. Instead, Parcells played it safe and elected to punt, showing trust in his defense.

Prior to the punt, Madden showed his appreciation for the style of play being demonstrated by both teams, “We are seeing very good defensive football here. We’re seeing crisp football, we’re seeing hard hitting, good tackling…this isn’t one of those things that is just conservative offense, it’s the defenses making the offenses look conservative.”

Two quick completions moved the 49ers to midfield before the drive was stymied, and the compelling game-within-the-game between Rice and Collins was on full display. Following a deep-ball pass breakup by Collins, Madden excitedly professed, “There is one confident corner back. He loves to play against Jerry Rice, and he’s tough on Jerry Rice. He likes to play him physical; he feels that he can get up there and bump him around, and then if he does get by him that he has enough speed to run with him.”

San Francisco punted away without attempting a single rush. Conversely, New York’s second drive of the game saw them return to form as they employed their familiar, bruising ground attack.

While incorporating a couple of wide runs by Meggett and a deft scramble under pressure by Hostetler, New York leaned more into the inside power runs by Anderson. Three of the Giants first downs on the time-consuming drive were on the ground as New York hogged the ball for 8:32 while traversing 56 yards over 14 plays.

More of the familiar also came by another name well known to San Francisco. Mark Bavaro, who made his first two catches on the drive, was highlighted by Summerall and Madden after making a nifty move to avoid a tackle. Summerall said, “When you ask Ronnie Lott what you have to do to stop the Giants, the first thing out of his mouth is ‘we have to stop [Bavaro].’” Madden followed, “Lott has a lot of respect for Mark Bavaro… Bavaro was a very physical player who’s turned into an intelligent player.”

Mark Bavaro

After Bahr kicked the Giants to a 6-3 advantage with exactly 1:00 remaining in the half, Montana led a quick-strike offensive that knotted the score 6-6, seconds before intermission.

Notably, Rice’s first big catch of the day, 19 yards to kickstart the drive, saw him beat zone coverage by Reasons. The Giants did manage their first sack of day, and it could not have come at a better time. After Dorsey’s personal foul penalty gave the 49ers a first down at New York’s 21-yard line with 21 seconds on the clock, Marshall threw Montana for an eight-yard loss. Montana had been forced to take the sack as Lawrence Taylor had also rushed from the opposite side, hemming the quarterback in the pocket without an opportunity to escape or throw the ball away.

Leonard Marshall and Joe Montana

During the hectic action, Madden again delighted in the high level of the competition. “You think of the last time they played on the Monday night, with the 49ers winning it 7-3. This is the same type of game, a very intense game and excellent defense by both sides. You know they say, ‘bend a little but don’t break’? They’re just bending very little and not breaking at all on either defensive side… I think the last time they played we talk about the intensity and what it meant. This game’s for a championship. This is sudden death, there’s no tomorrow. The winner goes on to the Super Bowl and the loser’s forgotten.”

Although possibly being disappointed by not going into halftime with the lead, one major trend in New York’s favor over the course of the first half jumped off the page. Despite holding the ball for only three possessions [discounting the half-closing kneel-down at 0:03] to San Francisco’s four, the Giants time of possession showed a wide advantage of 17:42 to 12:18. New York controlled the pace of the first 30 minutes, both offensively with their controlled blend of run and short passing, and defensively by disrupting the 49ers timing with tight coverage and pocket pressure.

During the halftime intermission, studio analyst Terry Bradshaw graphically illustrated how the Giants defense successfully accomplished slowing down the 49ers normally explosive offense. The tight coverage on outside receivers Rice and Taylor combined with pressure on Montana, forced him to check down to the third option; deep passes were a near impossibility unless there was a defensive breakdown. Thus far, New York’s execution had been near perfection save for a handful of plays.

The second half started frustratingly enough, as after back-to-back first downs, the once-promising drive was stalled by an offensive holding penalty that couldn’t be overcome. One misstep is all it takes to dramatically alter the course of a contest between two closely-matched teams. A mistimed gamble proved catastrophic after the Giants punted the ball to the 49ers.

Portending a reversal in 49ers fortunes, returner John Taylor swung the momentum to the home team’s side on the punt. After he caught the ball on the San Francisco 8-yard line, Taylor counter-stepped right, drawing New York’s coverage out of their lanes, then sprinted up field to his left behind a wall of interference before being pushed out of bounds at the 39-yard line. The 31-yard return electrified the crowd and fired up his teammates. Particularly damaging to New York, Taylor’s advance resulted in a meager 24-yard net in field position change.

San Francisco instantly capitalized.

Montana dropped back, and for perhaps the first time all day, had a clean pocket to throw from. John Taylor caught the high pass near the left sideline over the outstretched hands of the leaping defender Walls, and traversed the sideline unimpeded to the end zone as there was no safety help in the vicinity. The diving tackle attempt by Guyton was too little, too late as Taylor hopped on one foot to stay inbounds and cross the goal line for the game first touchdown at 10:28.

John Taylor accounted for 92 yards on two successive plays. Madden said, “Joe Montana had a little time, John Taylor is equally as dangerous as anyone in this league. Everson Walls, who’s been a heck of a cornerback over the years, took a gamble, took an angle, and when he did Taylor caught it, it was a touchdown.” And added, “And of course, John Taylor started it all off, and it’s usually a special teams play that will start it off… that punt return really gave the 49ers life.”

Walls said, “I went for the ball. I got one hand on it, but he had two. My break was good, my execution was bad. I just said, ‘Oh shit,’ I knew he was gone. But the guys on this team believe in me and when we came back on the field it was business as usual.”

Unfazed, the Giants offense returned to work at settling the game and quieting the crowd.

A first-down pass, good for 19 yards to Mark Ingram, put New York close to midfield. Breaking from tendencies, New York frequented the air as seven of the drive’s nine plays from scrimmage were passes, including all of the first downs [one via a pass interference penalty]. Covering 49 yards over 6:03, Bahr closed the gap on the scoreboard with a 46-yard field goal.

Ottis Anderson

Madden noted how, despite the 49ers defense adjusting by double-covering Meggett and forcing Hosteler to find other options, the overall flow of the game was unfolding as the Giants desired, “This is where the Giants are so tough. They just get the ball, even though the 49ers scored on one play, and methodically drive it down on you and take everything out of you.” Summerall added, “Bill Parcells said, ‘we like to make the game shorter.’”

San Francisco struggled to pick up where they had left off when they got the ball back. Montana opened the drive with a 10-yard completion to the heavily covered Rice on first down, but a false start penalty disrupted their rhythm. A short dump-off and ugly overthrew were sandwiched around a shared sack between Lawrence Taylor and Erik Howard. The 49ers punted the ball to Meggett who attempted to duplicate John Taylor’s heroics with an 18-yard return to the Giants 45-yard line.

Anderson seized the moment as well, as his 27-yard run around right end on third-and-one placed the Giants, yet again, inside the red zone at San Francisco’s 19-yard line. He had the opportunity to take the ball inside the 10-yard line but was dragged down by a desperate Lott who withstood a stiff-arm by Anderson.

The third quarter closed with the Niners ahead 13-9, but the Giant’s grinding attack was beginning to take its toll on San Francisco’s fatiguing defense. The gap in time of possession had widened to 30:31 for the Giants and 14:29 for the 49ers, who had the ball for only five plays in the quarter.

The Big Players and Big Moments

The decisive period commenced with New York again failing in the red zone. Two incomplete passes preceded an incomprehensible missed field goal by Bahr, who pushed the ball outside the left goal post from the right hash. “I rushed that one,” Bahr said, “The footing was good. I had no excuse for missing it.”

The demoralizing moment appeared to snowball. New York’s defense sagged as Montana connected on a first down pass for 14 yards to Rice, which Craig followed up with a seven-yard rush through right tackle. The respite of a false start penalty allowed the Giants defense to regroup. Lawrence Taylor forced a third-down incompletion with a hurried throw where he inadvertently kicked Montana in the knee as he lunged for the ball during its release.

Lawrence Taylor pressuring Joe Montana

Seemingly going tit-for-tat, on the second play of the Giants possession that followed the punt, Burt dove heavily into Hostetler’s knee as he followed through on a pass attempt. Hostetler left the game for the rest of the series, which ended quickly as backup quarterback Matt Cavanaugh was ineffective, throwing two ugly incompletions. As doctors, trainers, and coaches huddled about Hostetler on New York’s bench, their defense seethed.

Marshall said, “I’m not going to lie to you. That Burt hit motivated the hell out of me. I wanted to be a guy Jeff could count on. The guys were upset because Jimmy Burt used to be one of ours. When I say it was a dirty hit, it could have been one of the cleanest hits in football. We kind of took personal offense to it because Jimmy was one of our own. If it had been another guy on the team, maybe it would have been a different deal.”

Burt said, “I was just following through on the play. I wouldn’t want to hurt him. I was hoping he was OK. He’s tough. I always knew he was tough.”

Hostetler said, “Coach Parcells asked me how the knee felt, if I could go several times. Finally, I told him I was going. As long as it was stable, I was going back in. This was a huge game and I’ve waited a long time for the opportunity.”

The heat-of-the-moment outrage fired up the Giants defense, who took the field at the Niners 23-yard line at 10:50 after the exchange on the punt. San Francisco called time out before snapping the ball, as Montana did not like the look of New York’s defensive formation.

Madden articulated the importance of the series during the pause, “This is where the defense of the Giants really has to come through. They led the league in turnovers, and if ever you’re going to make something happen, if you’re ever gonna come up with a defensive play that’s gonna be a turnover, it’s a tackle, it’s a tip, a bounce, it’s something, the Giant defense may have to be the one to do it.”

A Craig run to the right for no gain and pass break up by Johnson on John Taylor set up third-and-10, and the transformational moment that significantly altered the course of both franchises for years to come.

Madden again anticipated an impending big moment upcoming before the snap, “Now this is a good situation to get that turnover, third-and-long. That’s usually when you get them. You usually get them on third-and-long when they have to force the ball down the field. Now Montana’s smart enough, he’s not gonna give you one. You might get one, but he’s not gonna give you an easy one. And if the defense doesn’t get it here, they have to stop them and hope to get a big punt return from Dave Meggett.”

One of Madden’s most well-known sayings was, “big players make big plays in big games.” It was at this point that the biggest names of both teams converged.

Under center in the standard Pro-T formation (the 49ers had long abandoned their desired three-receiver set after Montana had requested two backs for additional support against the Giants pass rush), Montana overlooked the Giants unique nickel formation. The three down linemen were shifted left with Lawrence Taylor on his opposite side over the tight end in a two-point stance, showing rush. Safety Greg Jackson momentarily occupied the spot of a fourth linebacker before dropping back, giving Montana different reads to consider.

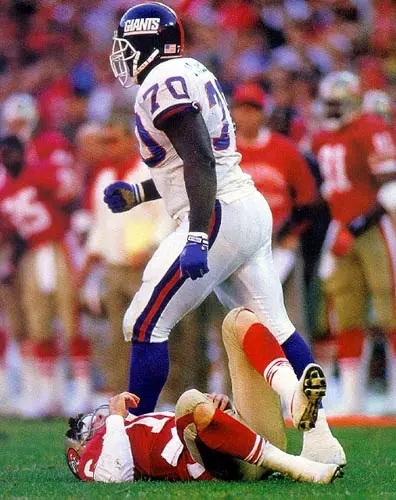

Leonard Marshall dislodging the ball from Joe Montana

Off the snap, the Giants corners pressed Rice and John Taylor while Taylor and the linemen crashed the forming pocket. The remaining five defenders dropped into a layered zone coverage that blanketed the middle of the field. San Francisco’s guards and center formed a wall that stalemated the middle of the rush, but the ends were pierced by Lawrence Taylor and Leonard Marshall. Taylor was blocked one-on-one by tackle Steve Wallace; Marshall contended with a double-team by Bubba Paris and Tom Rathman. Initially cut by Paris then cracked-back by Rathman, Marshall’s motor never sputtered. Initially crawling, then gaining momentum once back on his feet, he relentlessly pursued Montana while Taylor deked his way around Wallace. Montana rolled to his right way from Marshall’s pressure, Taylor sprinted across Montana’s face as he pulled up to heave a pass downfield in Rice’s direction. During his windup, Montana was violently upended from behind by Marshall, face-first, into the turf, separated from the ball which floated toward the chaotic maelstrom still taking place at the line of scrimmage. Somehow the ball bounced through the awaiting hands of Collins and was recovered by Wallace. No one seemed to notice the conclusion of the play however, as all eyes were on the crumpled body of Montana, agonizingly writhing on the grass.

Leonard Marshall and Joe Montana

The broadcast team in the booth seemed as bewildered as the fans as the game came to a halt for over four minutes of real time. The tandem alternated between analyzing replays from different angles while speculating on Montana’s well being. Meanwhile support staff administered to Montana on the field.

Summerall: “Montana is still on his hands and knees.”

Madden: “I’ll tell you that is the one thing we know about Joe Montana, we know about his back, and he really took a shot in that back. Although he was rolling to his right it was still his back side.”

Summerall: “Montana with all kinds of time early.”

Madden: “It was good defense downfield, he had no one to throw to, they knocked him out of the rhythm. Then you see Taylor miss and right there is the hit, Leonard Marshall coming from the back side.”

Summerall: “Boy.”

Madden: “George Seifert I think, right now, is more concerned about his quarterback because that is a real shot. Joe Montana missed practice on Friday and Saturday with the flu so he’s a little weakened, but even if he hadn’t missed practice, you can’t take shots like that. He is still down.”

Summerall: “Usually he has that sense of when someone is coming from the other side. In this case, there’s no way he could have seen Marshall.”

Madden: “I think he was trying to get away from Taylor. Remember Lawrence Taylor was the first guy there, he was trying to avoid him. Then in doing so, Leonard Marshall got him from behind.”

Marshall said, “I was blocked. I’d been cut at my feet. I was crawling. Joe Montana rolled off to the right, telling Jerry Rice to keep running. As he pulled up, I dove, trying to strip the football… I heard him cringe, but it was a clean hit. I never go after people to hurt them.”

Leonard Marshall

Walls said, “You could hear the hit. It was scary.”

Once Montana was helped to the sideline, play resumed with San Francisco punting the ball to the Giants at 9:17. To the surprise of many, Hostetler was back under center for New York. Even more of a surprise was his second-down scramble through traffic for a gain of six yards. He deftly evaded would-tacklers on his way to the sideline, as if he never took that hit to the knee minutes earlier.

The scramble wasn’t good enough for a first down, however. After Anderson was stuffed for a one-yard loss on third-and-one, the Giants punt team took the field while the 49ers defense celebrated. Having already absorbed one devastating blow from Marshall on Montana, the next strike on San Francisco was delivered by Reasons.

Fake punts were not all that out of the ordinary for the Parcells’ coached Giants. One of the better known plays from Super Bowl XXI was the momentum-turning sneak by Jeff Rutledge, who shifted under center from a punt formation protector early in the third quarter. This initiated the decisive surge over the Denver Broncos. This time, there was no backup quarterback on the field and there was no shift tipping intentions. Reasons, calling signals as the protector in the punt formation, had the green light to call the fake any time he saw the opportunity.

He received the direct snap from center and barreled through a hole wide enough to accommodate a bulldozer. Chugging up field with the ball tucked under his arm and only return man John Taylor between him and the elusive goal line, Reasons was cut down short of pay dirt, but not before advancing 30 yards of precious real estate.

Gary Reasons running the ball on a fake punt

Reasons said of the call, “They were getting ready to get their wall going to Taylor, and I noticed an opening on the right. We had the play on all game, and I had the go-ahead to call it when I saw it,” and on attempting to elude Taylor downfield, “I was trying to set him up. I have no moves and he cut me down. I just didn’t want to fumble.”

Suddenly it was New York that was celebrating, as they found themselves within striking range and the lead with under seven minutes to play. If only they could conquer the confounding red zone.

New York’s hopes for a go-ahead touchdown were quickly extinguished by the Niners resolved defense. A short Anderson run, and two incompletions preceded Bahr’s 38-yard field goal to trim San Francisco’s lead to a single point at 5:47 of the final quarter.

Madden noted the elevation in tension of the decisive moments of not only the game, but of the season for one of the teams, “This is what you call fighting to get to a Super Bowl. Everyone is down there for every yard, the offense, the defense, the quarterback is fighting to get well. Knowing that at the end of this game the winner flies to Tampa, Florida. The losers, they forget ‘em.

“You can’t ask for a better championship game than this. You can’t think about the ‘what ifs’, you can’t think about the one that Bahr missed had he made it they’d be ahead now, you can’t think about Carthon doin’ that, you can’t think about Joe Montana… you have to think that ‘this is it’. There’s five minutes forty-seven seconds left to go… you’re one point down on one side or you’re one point up on the other side and you have five minutes and-a-half to do something about it.”

Marshall and the Giants defense picked up exactly where they left off, forcing a fumble. As Craig approached the line with a first-down handoff, the hard-hitting Marshall battered him full-force from the side, knocking the ball loose before the ball carrier’s knee touched the ground. As with Montana’s fumble, the 49ers maintained possession as Paris fell on the loose ball.

Watching the replay, Madden exclaimed while reviewing the tenacity of New York’s defenders who crashed toward Craig from all angles, “That’s real defense!”

The next play stunned the Giants and revived the crowd, which had been silent since Reasons’ fake. Eschewing the run, the 49ers went back to what they do best, moving the chains through the air. Provided with good protection, Young found Jones in the Cover-2 zone’s deep middle – behind the linebackers on the hash and in front of the safeties. The lightning-fast pickup advanced the ball 25 yards to the Niners own 49-yard line with the clock running under 4:30.

Seifert said, “I thought we had the game won, to be honest with you.”

“I even spiked the ball, because I pretty much thought it was over,” said Jones. “That’s what I was yelling and that’s what I felt. At the time, [the Giants] thought it was over too.”

Back-to-back rushes by Craig totaled 11 yards and a first down – the 49ers only rushing first down of the game – with just under three minutes to go.

Parcells paced the sidelines, choosing to retain New York’s three timeouts, as the Candlestick crowd stood and cheered the seemingly imminent trip to a third consecutive Super Bowl.

The next carry by Craig was his last as a 49er.

“Going into that series, the feeling was we’ve got to stop them and let our offense do something with the ball,” Pepper Johnson said. “Then, after [Young] completed that big play, all 11 guys started yelling, ‘Turnover, we need a turnover real bad.’”

The Giants countered the 49ers Pro T set on first down with five men on the line of scrimmage – three linemen plus Taylor and Banks up on the edges in two-point stances. The two inside linebackers were only two yards off the line, obviously prepared to plug any inside gaps. Both corners were in bump position on Rice and Taylor but had their eyes on the backfield anticipating run.

Off the snap, Young handed to Craig on an inside run, where there appeared to be a crease. The middle of the defense held stoutly for a moment, then Craig turned sideways and in the blink of an eye the ball squirted backward into the hands of a lunging Lawrence Taylor.

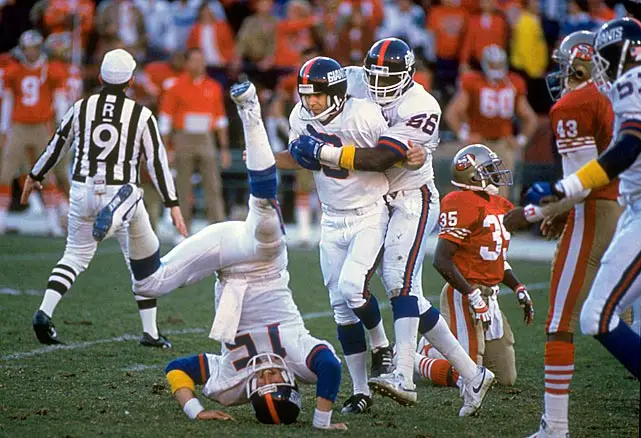

Lawrence Taylor recovers a fumble late in the 4th quarter

The play happened so quickly that Summerall’s normally timely call was a beat behind the action, “…and the Giants have the ball!” he exclaimed as Pepper Johnson had already signaled the change of possession amongst the group of jumping, fist-pumping, white-jerseyed defenders.

The game’s first turnover occurred during its 57th minute.

Craig said, “All I know is I hit the hole and the ball was gone. I guess someone’s helmet knocked it out. It’s hard to say what happened.”

Johnson said, “All day long he had been bobbling the ball.”

During the brief pause for the sides to change, slow-motion replay revealed the catalyst for the game’s dramatic shift. In the morass at the point-of-attack, Erik Howard fought off his block and knocked the ball out of Craig’s hand with his helmet. “Late in the game, this time of the last game, they went with the inside run,” Howard said. “We were in a ‘Stack D,’ I was over (center Jesse) Sapolu. They gave me a double-team, so I dropped down and split the seam. I can’t say I went specifically for the ball, I just went for his mid-section.”

Burt said, “Craig didn’t even get hit. He was fumbling before he got hit. On the series before, he almost fumbled because he was a little tight.”

Lott noted the auspiciousness of Lawrence Taylor, who was in the right place at the right time for the recovery, “Great players have a certain magnetism about them, and they make plays like that. That’s why he is considered the greatest [defensive] player of all time. It couldn’t happen to a better person.”

Erik Howard and Lawrence Taylor’s combined efforts put the ball in New York’s hands at their own 43-yard line with 2:36 to play and all three of their timeouts.

Hostetler made a remarkable play under pressure on first down. The fierce pass rush up the middle, almost immediately after the snap, barely allowed Hostetler to escape the grasp of two defenders, let alone set his feet and look downfield. Sprinting toward the right sideline and gesturing downfield with his left hand, he launched the ball as Burt dove at his legs. The deep pass found Bavaro, who found an open spot in front of a 49ers safety just inside the numbers, at San Francisco’s 41-yard line. Three tacklers eventually dragged him down at the 38-yard line for a gain of 19 yards, right on the precipice of field goal range as the clock ran to the two-minute warning.

Hostetler said, “The pass to Bavaro was supposed to be a drop-back pass. But when the rush got heavy, I moved to the right and the flow went with me. Mark made a great move against the grain to get open.”

A potentially disastrous four-yard loss on an Anderson run was quickly rectified by a 13-yard sideline catch by Stephen Baker, who emphatically planted both feet in bounds.

Stephen said, “When they called the play, I said, ‘You know what, this is it. This is gonna be the best route I run in my life. This is what I worked all my life for, this one moment right here to get our team to the Super Bowl. I ran that route so hard…It was a ten-yard out and then I bursted up field for 18 yards, acting like I’m running deep and then stop on a dime, and Hostetler’s rolling outside to my side fires it in there for the sticks.”

The Giants took their first timeout at 1:10 to contemplate the best option for the critical third-and-one.

Despite being stymied by San Francisco’s stout front – Andersons’ fourth quarter rushing totals to this point were four carries netting zero yards – New York’s staff did not waiver in their confidence. Erhardt said, “We let Ottis take it and hit it up in there, we felt we could always make a yard. We had that mentality.”

The 49ers lined up in a 4-4 front with a Lott cheating up to linebacker depth creating a nine-man box, while the Giants had only seven men – the five interior linemen plus two tight ends – for interference. The two wideouts split left and their respective corners would be uninvolved in the upcoming pivotal scrum.

Should San Francisco hold the line here, New York would be faced with either a field goal attempt of no less than least 46-yards, the edge of Bahr’s range on grass, or going for a fourth-down conversion. With approximately one minute on the clock after the upcoming play, and the Giants having only two timeouts at their disposal, the game and the trip to the Super Bowl would almost certainly belong to the 49ers if the Giants failed to convert.

All nine San Francisco defenders in the front stormed the line of scrimmage at the snap. New York’s out-manned line forged enough of a crease between left guard William Roberts and left tackle Jumbo Elliott for Anderson to slip between them and use his powerful leg drive to fight through the first tackler and lunge beyond the sticks to the 27-yard line for the first down. He landed on the turf with three defenders piled on top of him.

The two-yard gain may not look all that impressive on paper, but it may have been the most significant carry of Anderson’s career.

There was a brief stoppage at 0:51 that caused confusion over timeouts, which referee Jerry Markbreit ultimately ruled an officials’ timeout to spot the ball. Both teams were content to allow the clock to run – the 49ers, hoping to minimize the number of plays they needed to defend; the Giants, wanting to end the game with the ball in their hands.

To that end, the Giants took their wide receivers off of the field and presented a three tight end, goal-line formation with Anderson as the only player in the backfield. San Francisco came to the line with a 10-man front and again, Lott cheating toward the line of scrimmage creating an 11-man box. The closing moment of the NFC’s championship, and the right to participate in the biggest stage of modern professional sports, had taken on the look and feel of early 1920’s football where all 22 men would engage in hand-to-hand combat over the line of scrimmage. Leather helmets and a bloated rugby-style ball would have been all too appropriate.

The first-down rush by Anderson, behind right guard Bob Kratch this time, again saw him evade the gap-shooting Lott and power for two yards after contact. For good measure, Anderson absorbed a blow from behind by his own diving teammate, tackle Doug Reisenberg.

The Giants took their second timeout at 0:12 with the ball on the 25-yard line. The next play, again, was contested as if on the goal line. Every precious inch of field was being bitterly fought over. The play was the simplest, most basic call in any team’s playbook, the quarterback sneak. Hostetler dove off the left shoulder of Oates into the foray for a meager, yet not so insignificant, gain of a single yard.

New York stopped the clock at 0:04 with their final timeout to allow the field goal unit time to set up, after which San Francisco called the obligatory timeout to “ice the kicker.”

Once the ball was set at the 24-yard line, just a hair to the left from dead center of the goal posts, and the play clock activated, the teams came to the line of scrimmage. The 49ers aligned strong to the left of the Giants formation, seven of their defenders bunched tightly, with the other four widely spaced to the right. The overload was a decoy, designed to pull New York’s blockers over and allow the end man on the far right a lane to sprint toward the flight of the ball.

Matt Bahr

The brilliant tactical concept nearly succeeded. As Hosteler flawlessly received the snap from center and placed the ball and Bahr approached with his leg cocked – the lone 49er flashed unimpeded from his end position through a wide gap in the protection, just as it had been drawn up. However, Bahr’s kick proved to be perfectly imperfect. He pulled the ball ever so slightly left, getting it just beyond the extended fingertips of the leaping Spencer Tillman, and its flight straightened out just enough to pass inside the left upright as the clock reached 0:00.

Tillman said, “I just tried to get to it. IU didn’t come from the outside, my normal alignment. I went right behind the line of scrimmage and tried to dive over about three or four guys. I almost got it.”

Jubilant Giants jumped off the sideline and mobbed their kicker, while dejected fans and 49ers trudged off the field, their dream of a three-peat having been vanquished by inches and seconds.

The Analysis

At first glance, what the Giants had just accomplished seemed utterly remarkable.

Consider: New York dethroned the two-time defending Super Bowl champions without reaching the end zone. In fact, over the course of the two games the teams played that season, New York crossed San Francisco’s 30-yard line nine separate times and never scored a single touchdown, managing only six field goals. The other three possessions ended with a failed 4th-down attempt, a sack as time expired, and a missed field goal.

Giants celebrate Matt Bahr’s game-winning field goal

How they pulled off that feat was more-or-less winning the battle of attrition – the Giants totaled 68 plays from scrimmage to the Niners 41. Looking at those plays reveals much about the two teams. New York’s offense was balanced: 36 rushes vs 32 passes. San Francisco’s was heavily skewed: 30 passes vs 11 rushes – even though they played with the lead almost the entire second half. Underscoring their ground game’s absence, Reasons 30-yard fake punt run equaled the combined output of Craig and Rathman on nine total rushes.

Wallace said, “By us not running the ball, [the Giants] could lay their ears back and use their talent. It was guys having the freedom to rush and not worry about the run.”

This disparity points to the game’s most telling statistic, time of possession. The Giants had the ball almost two-thirds of the game: 38:59 to 21:01. (This ball control philosophy would be taken to its zenith a week later against the Bills in the Super Bowl.)

“I’ll tell you how we did it,” said Parcells. “We did it by not turning the ball over. We set a record for fewest turnovers in a 16-game season. We don’t make it easy for people. Yeah, I know, we’ve been called a conservative team, but you’ll notice this conservative team is still playing.”

The Giants feat was also historic. They were just the second team to advance to the Super Bowl without scoring a touchdown, after the Rams defeated Tampa Bay 9-0 in 1979 on three field goals. They were also only the second NFC team in 11 years to win the conference title as the visitor, the 49ers being the only other team to do so when they took down Chicago at Soldier Field in 1988.

Parcells told the press, “Any time you accomplished what we did, when you win on the road against this organization, you have to feel great. I feel great.”

Myron Guyton, Pepper Johnson and William Roberts celebrate

Niners linebacker Mike Walter said, “You think because you keep a team out of the end zone, you’re going to be OK. But it wasn’t enough today. We needed to have a three-downs-and-out with a punt, and we didn’t do that today. We needed to get our offense back on their filed. We didn’t do that.”

Although San Francisco had boasted a seven-game, playoff-winning streak entering the contest, the streak bracketing that run of success was ugly. This was the third consecutive post-season loss for San Francisco to end without Montana on the field. The 1986 Divisional Playoff saw Montana leaving the game in the second quarter with a concussion, and in the 1987 Divisional Playoff loss to Minnesota, Montana was benched at halftime in favor of Young.

Plaudits abounded for another stellar Giants defensive performance against the 49ers offense. Many cited the pressure generated by the pass rush and the effect it had on San Francisco’s timing.

Johnson said, “We wanted to hit [Montana]. We knew he’d get rid of the ball fast, but we wanted to shake the guy up and I think we did.”

Lawrence Taylor said, “I could tell Joe was getting frustrated. Any time you hit a guy like that and put pressure on him and not let him do the things he’s used to doing, you’ve done a good job.”

Parcells said, “We were able to hit Montana a few times early in the game, very hard. That was a big factor in the game. We hit their guy, they hit ours, both went down. That’s championship football.”

Wallace said, “When you have the talent they do and rush the passer on almost every down, they’re going to do some damage. We never did get the old running game established. It eventually hurt us. If you never get it going, eventually it will come back to haunt you.”

Seifert said, “The Giants did a great job of pass rushing, of mixing up their blitzes and four-man rushes. Obviously, that was a problem during the course of the game. There’s no question about that… They were relentless in what they did.”

Holmgren mentioned the 49ers early shift in approach to deal with New York’s rush, “They were blitzing us a little bit more than in the past, so Joe felt more comfortable with two backs in the game. It did take us out of our game plan a little bit [featuring 3-WR sets].”

Collins discussed covering Rice most of the game, who was limited to 5 catches for 54 yards, “I played a lot of mind games with him. I never said anything to him. I just stared him in the eyes.”

The Aftermath

Immediately after the game, there was much discussion of the biggest and most controversial plays that had taken place. Remarkably, all had been compressed within the final 10 minutes of playing time.

The most talked about were the two hits on the opposing teams’ quarterbacks.

Burt said of his hit on Hostetler’s knee that riled up the Giants, “Bart [Oates] was blocking me on that play. He lunged forward a little bit. When he lunged forward, I got around him. He missed the block and I think the guard was fanning out. When Eric Moore came to fan back out, he was late. I knew he was going to come back and cut me. I stayed low. I had to get myself down low, otherwise he’d take out my knees. So, I came in almost like a submarine because Bart was going to cut my legs. He had to do that or grab me. These guards were going to do the same. They tried to cut me the series before that, so I knew I had to stay low once I got past them. So, I came in low, and I hit Hostetler low. I had to protect myself. They made a big deal about it.”

Oates took his share of responsibility, “[Burt] got around the edge and I ended up pushing him into Jeff where it hurt Jeff’s knee. That was my fault, it wasn’t Jim’s fault. He got blamed for it – people thought it was a cheap shot. But he got my edge, and I was trying to do what I could, and I pushed him. I wound up pushing him right into Jeff’s knee.”

Hostetler held no grudges, “I don’t know if it was a cheap shot. I know him. I don’t think he was trying to hurt me. After the game he said, ‘Good job.’”

No one accused Marshall of laying a dirty hit on Montana, but that was clearly the most violent of all the impacts delivered that day.

Marshall recounted the sequence of events, “I slipped past Bubba (Paris), got cut, got up and had a chance to hit Montana. I wasn’t trying to put him out of the game or end his career…I could have easily stayed down after I was blocked. But this is big-time football, and big-time players make those plays.”

Rathman said, “[Marshall] was kind of stumbling, then I pushed him, and he went down. I laid on him for a second, then I got up and he started to chase. Great effort on his part… The Giants played great defense.”

Paris said, “I thought [Montana] would get rid of it. I didn’t even think of [Marshall].”

Montana was able to make his way to the post-game podium after the contest to speak to the press, “I still don’t know what happened. I don’t want to sound like a coach, but I have to look at the video. I don’t think it was the initial hit; I think it was the ground. I’m still having a tough time breathing deeply. Even if we had won, I wouldn’t have been able to play next week. The doctors will know more when they see the X-rays tomorrow.”

While not as controversial as a hit on a quarterback, there was a behind-the-scenes story that went mostly unnoticed on Reasons’ momentum-seizing fake punt. San Francisco only had 10 players on the field.