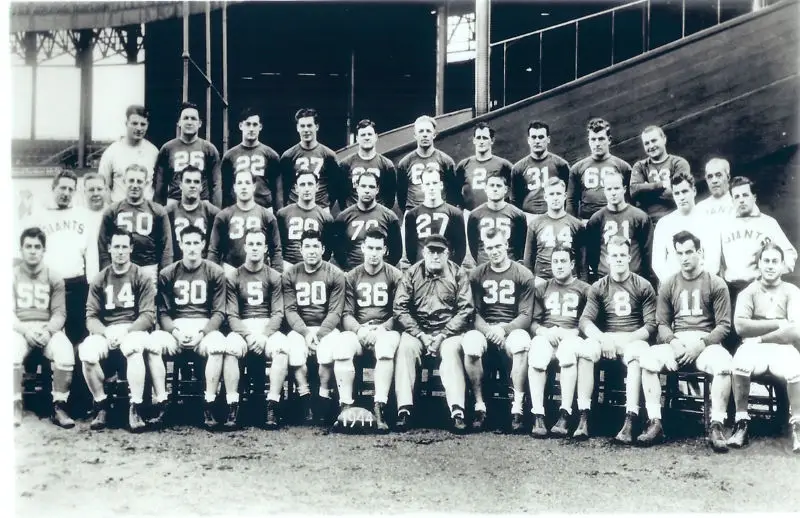

by Larry Schmitt | Jul 6, 2014 | Articles, New York Giants History

The NFL was in a struggle for survival as the manpower shortage created by World War II put a strain on the league’s primary resource, healthy young men. The War Manpower Commission had first dibs on able-bodied young men and it did not take long for the depletion to...