by Larry Schmitt | Mar 2, 2015 | Articles, New York Giants History

The 1933 season is the most significant in the National Football League’s early history. While being mired in the depths of the Great Depression, many significant changes were made during the offseason that ensured not only the fledgling league’s survival, but allowed...

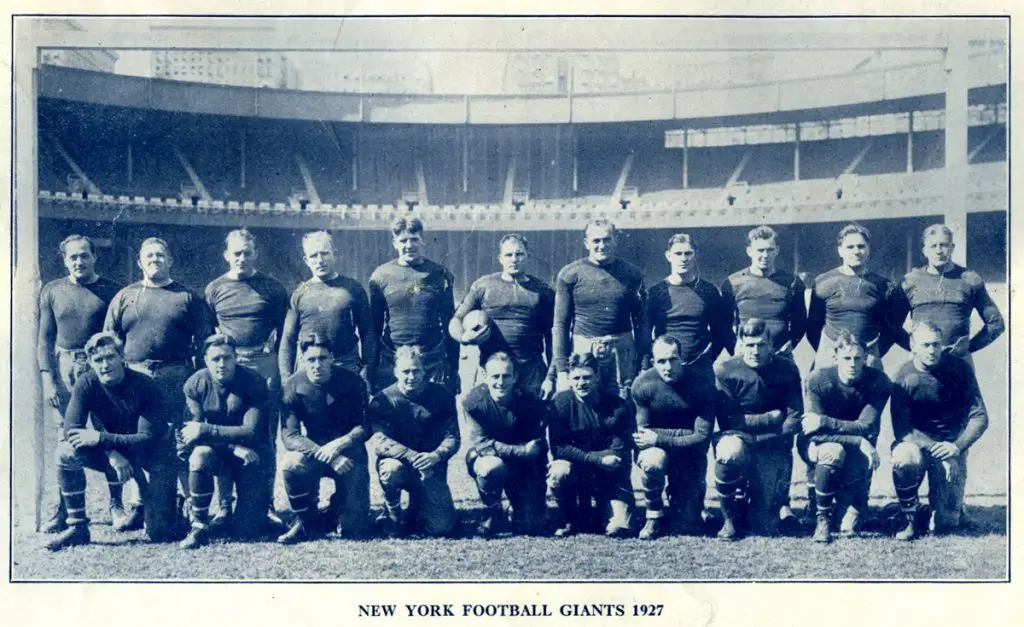

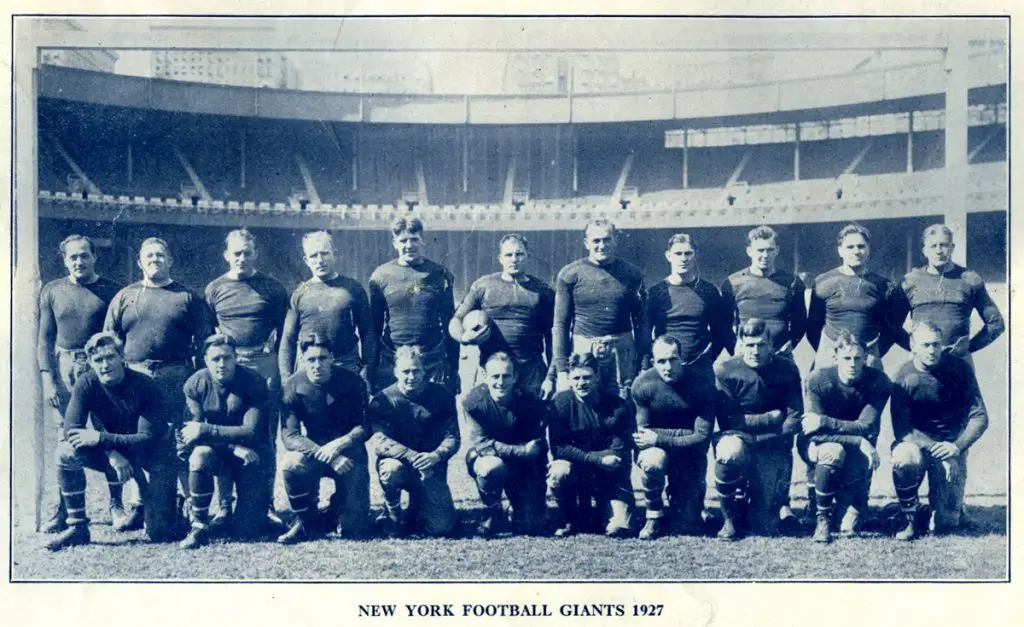

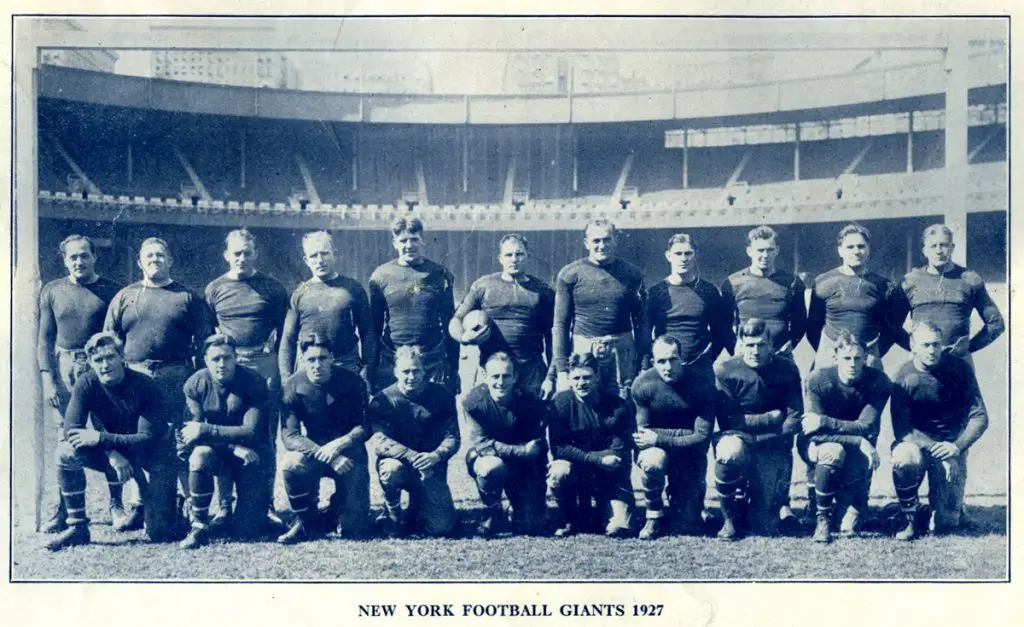

by Larry Schmitt | Jun 15, 2014 | Articles, New York Giants History

The early attempts to organize professional football were no doubt sincere. But results were minimal. In hindsight, it’s easy to see that trial-and-error was the guiding principal for many of the organizational efforts by the nascent National Football League (NFL)....