by Larry Schmitt | Mar 2, 2015 | Articles, New York Giants History

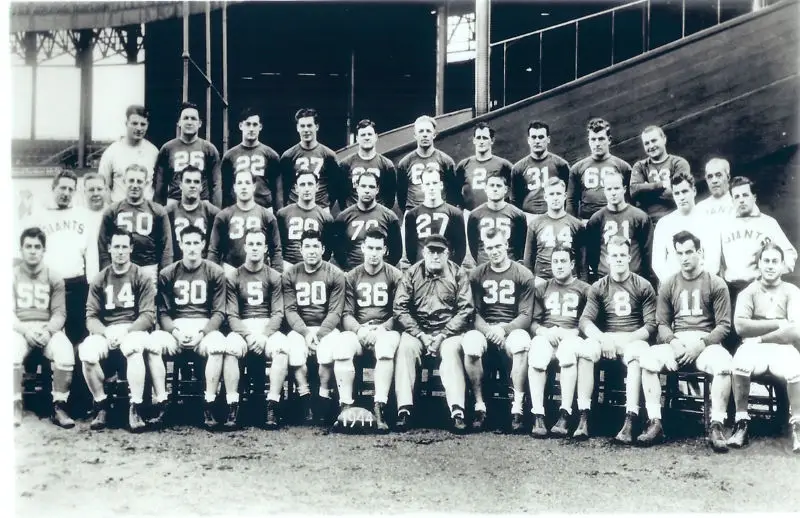

The 1933 season is the most significant in the National Football League’s early history. While being mired in the depths of the Great Depression, many significant changes were made during the offseason that ensured not only the fledgling league’s survival, but allowed...

by Larry Schmitt | Dec 31, 2014 | Articles, New York Giants History

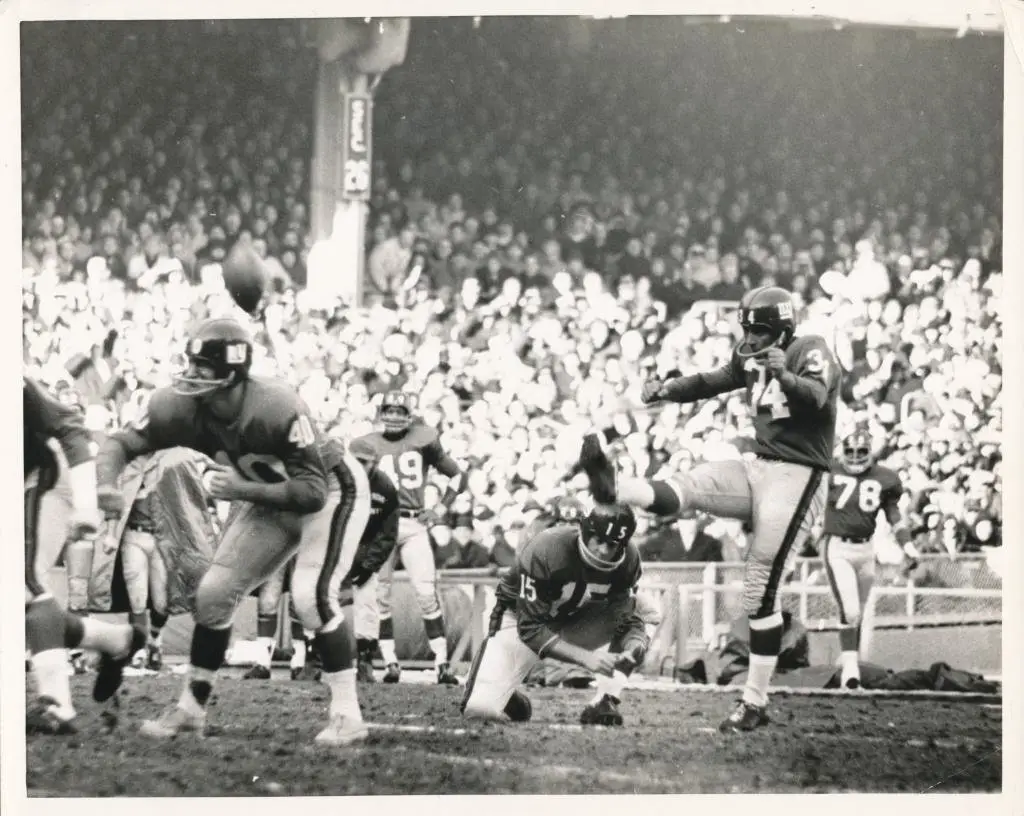

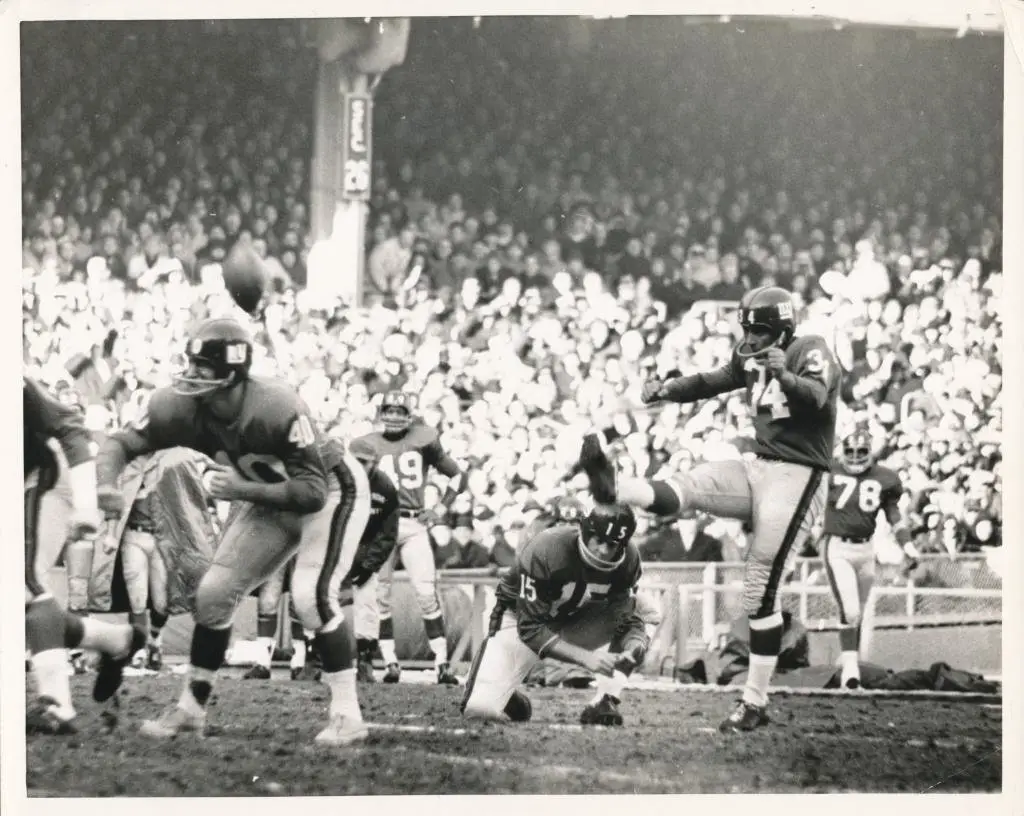

By Larry Schmitt with contributions from Daniel Franck and Rev. Mike Moran When most Giants fans think about a kicker making a clutch kick in a pressure situation, they most likely recall Matt Bahr or Lawrence Tynes kicking the Giants to the Super Bowl. There was a...

by Larry Schmitt | Jul 6, 2014 | Articles, New York Giants History

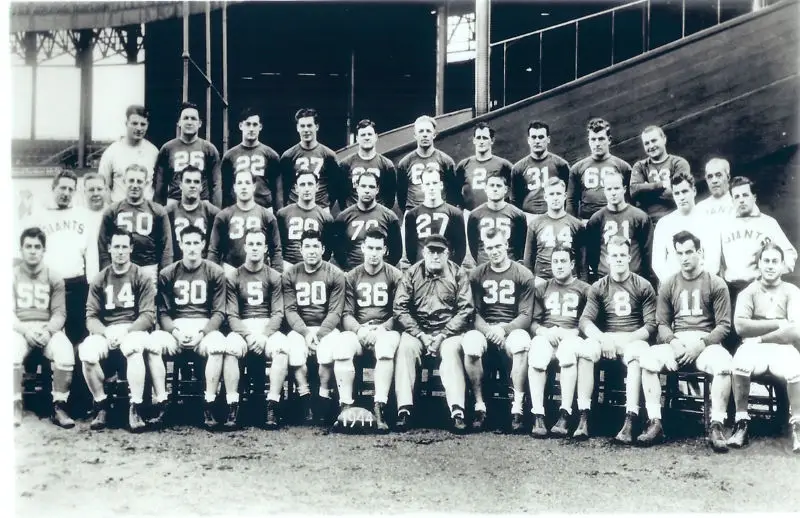

The NFL was in a struggle for survival as the manpower shortage created by World War II put a strain on the league’s primary resource, healthy young men. The War Manpower Commission had first dibs on able-bodied young men and it did not take long for the depletion to...