by Larry Schmitt | Nov 14, 2021 | News and Notes

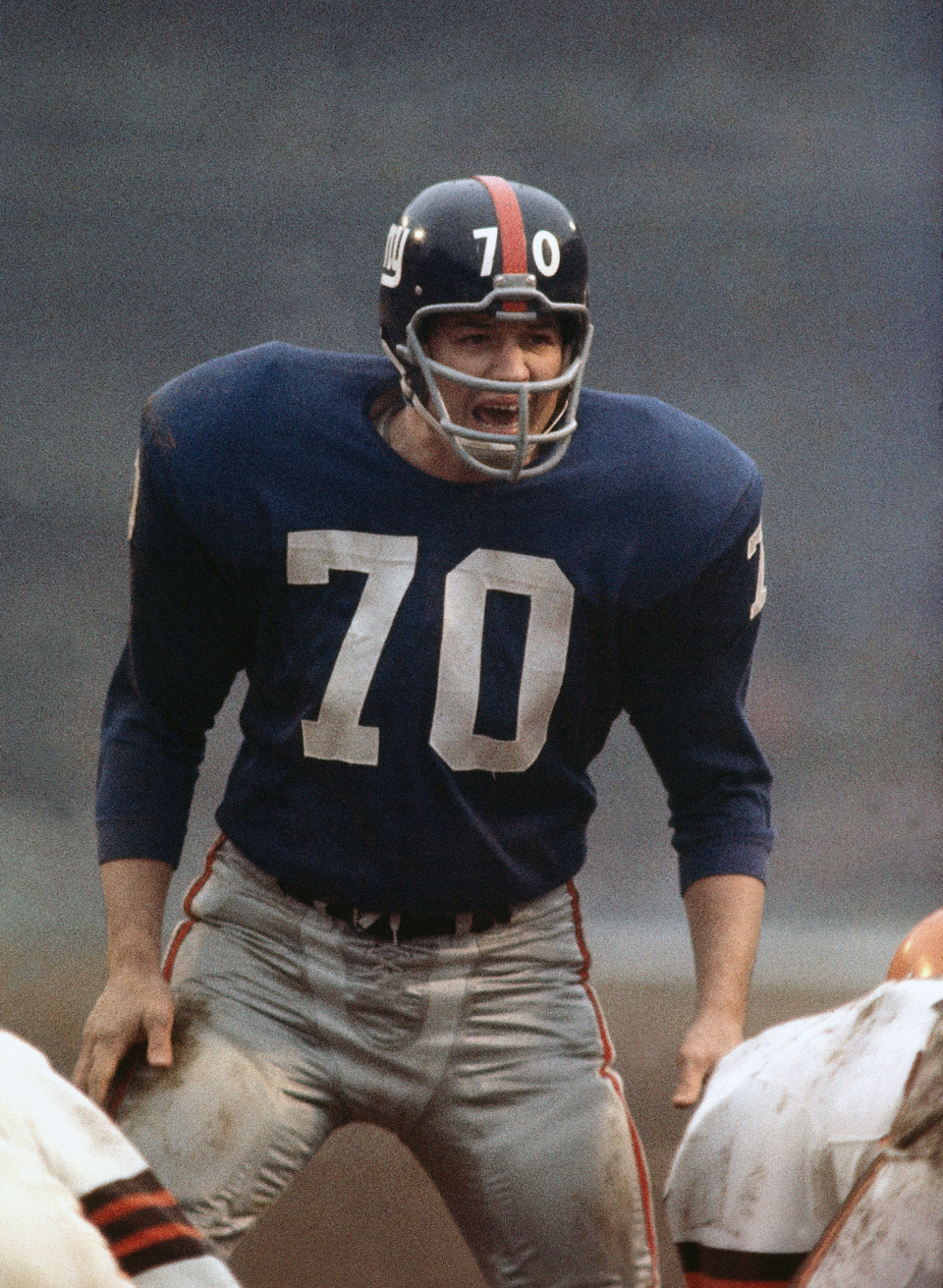

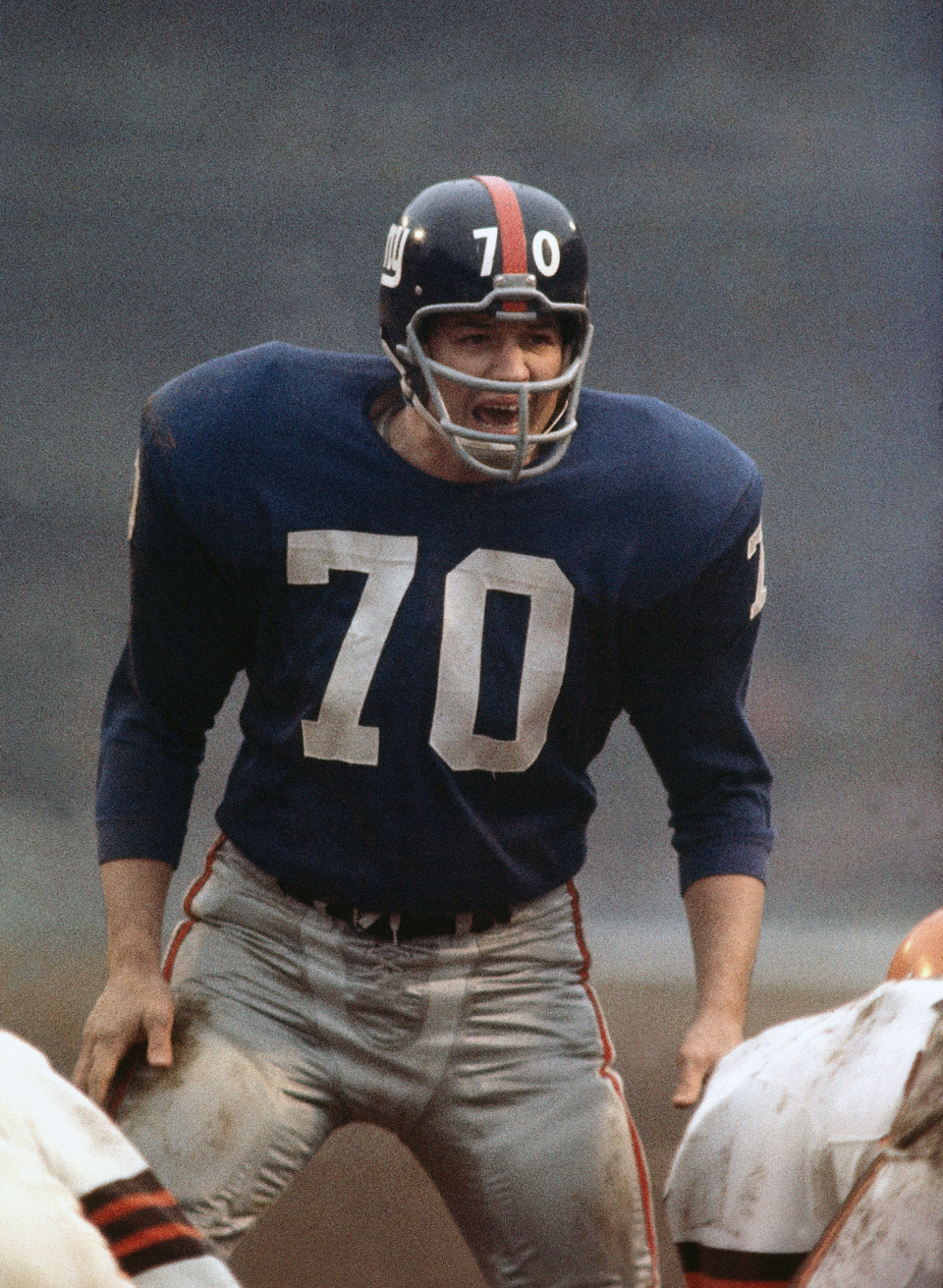

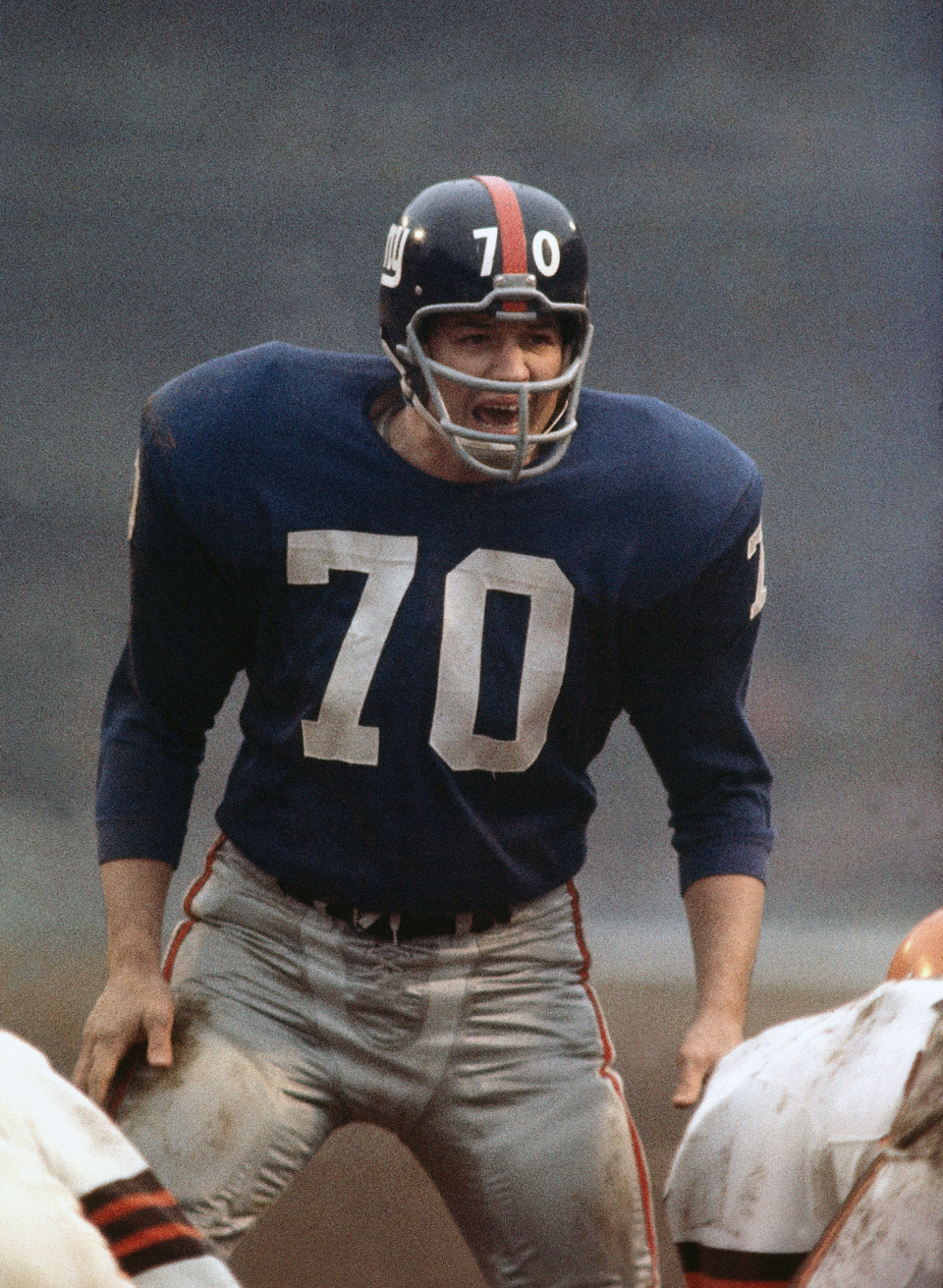

Robert Lee Huff, popularly known as “Sam,” an All-Pro and Pro Football Hall of Fame member who helped popularize professional football during its ascendancy in the late 1950s, and the first recognizable personality who played only defense, passed away at the age...

![New York Giants 27 – Cleveland Browns 13]()

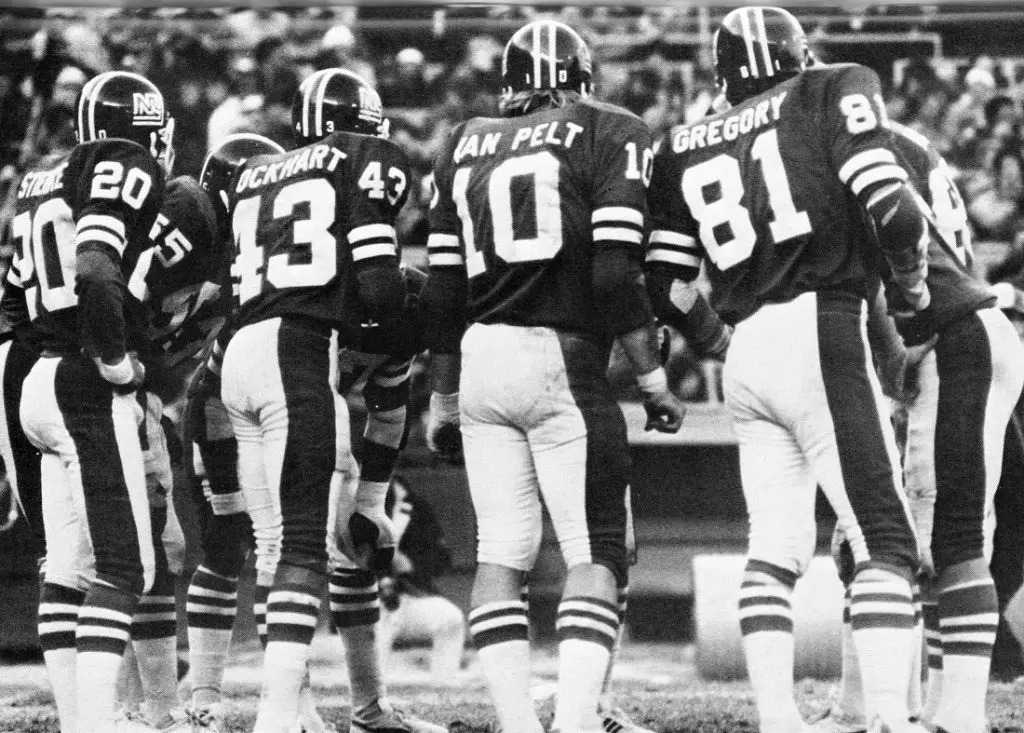

by Eric Kennedy | Nov 27, 2016 | News and Notes

[contentblock id=1 img=html.png] NEW YORK GIANTS 27 – CLEVELAND BROWNS 13… The New York Giants won their sixth game in a row on Sunday by defeating the winless Cleveland Browns 27-13 at FirstEnergy Stadium in Cleveland. With the victory, the Giants...

by Larry Schmitt | Aug 7, 2016 | Articles, New York Giants History

The first chapter of the New York Football Giants history closed on December 29, 1963. Up until that time, one of the cornerstone franchises of the NFL, the Giants prospered on the field while they regularly struggled financially to stay afloat. The franchise nearly...

by Larry Schmitt | May 30, 2015 | Articles, New York Giants History

By Larry Schmitt with contributions from Daniel Franck and Dr. Bruce Gilbert The 1956 season was a watershed moment for football in New York. Filled with potent portent, the campaign proved to be the penultimate piece of the puzzle for the ultimate explosion of pro...

by Eric Kennedy | Sep 10, 2013 | News and Notes

New York Giants Sign RB Brandon Jacobs: The Giants have signed 31-year old RB Brandon Jacobs to a 1-year contract. Jacobs was drafted in the 4th round of the 2005 NFL Draft by the Giants and played with the team for seven years from 2005-2011. He remains the...